During the half-hour phone call they bantered about the appearance of gray hair, the joys of getting their nails done and strategies to exercise more.

Amid the small talk, Beth Thompson dropped a bombshell. After living 16 months in a tiny home village in North Hollywood, she’d soon be moving into her own apartment.

Thompson and Tiffany Daniel have never met in person and likely never will. Daniel, an employee of the U.S. Department of Commerce, lives across the country in the town of Waldorf in southern Maryland.

She’s been speaking with Thompson by telephone for about six months after signing up with Miracle Messages, a nonprofit conducting an unusual social experiment in pursuit of its founder’s vision that companionship can be a force in improving the lives of homeless people, and maybe even more so if enhanced with a little spending money.

Beth Thompson tries to remain optimistic while living at the Alexandria Park Tiny Home Village in North Hollywood.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Over the last two years, about 200 volunteers like Daniel have become telephone buddies with people living on the streets of Los Angeles or, like Thompson, in shelters. About half of them, including Thompson, receive a monthly stipend of $750 as pocket money with no strings attached.

The two women text several times a day and speak by phone ideally at least once a week shortly after Daniel gets home from work. In reality, Thompson calls whenever she needs someone “to lend an ear.”

“I’ve called her sometimes at 2, 3 o’clock in the morning asking for advice, and she gives me good advice,” Thompson said during a recent visit at the Alexandria Park Tiny Home Village. “Always willing to give me good advice, telling me everything’s going to be OK, just try to relax and get some sleep. And I do. Everything’s worked out just fine.”

Besides being friends, Thompson and Daniel are participating in a controlled statistical study. USC’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work is surveying the phone buddies to measure the effects of companionship, with and without a basic income.

Miracle Messages is the evolving vision of Kevin F. Adler, 38, a serial entrepreneur of social enterprises. After finishing his graduate studies in sociology at Cambridge University, England, Adler was in San Francisco founding education technology startups when a 2013 visit to the grave of his homeless uncle precipitated self-questioning over his view of people living on the street as “problems to be solved rather than people to be loved.”

Miracle Messages founder and CEO Kevin F. Adler with a homeless man sitting in Union Square in San Francisco in January 2019.

(Paul Chinn/San Francisco Chronicle)

His answer was to start an experiment. He distributed 24 GoPro cameras to people living on the street to tell their stories.

“It was pretty heartbreaking,” he said.

On one of the clips, he heard someone say, “I never realized I was homeless when I lost my housing, only when I lost my family and my friends.”

Next he started asking street people if they had any loved ones they would like to reconnect with.

“One of the first individuals I spoke to was a man named Jeffrey who said he hadn’t seen his family for 22 years,” Adler said in an interview.

Adler posted a video on a Facebook page connected to Jeffrey’s hometown in Pennsylvania. Within an hour classmates and neighbors were liking it, and the local newspaper picked up the story.

Jeffrey’s sister said he had been a missing person for 12 years.

“I kind of had this realization,” Adler said. “Jeffrey is probably not the only one.” He began to think of homelessness as a poverty of relationships — “dislocation and isolation” — as well as a lack of money.

Beth Thompson receives a hug of support from Debby Moyer, near Thompson’s tiny home in the Alexandria Park Tiny Home Village in North Hollywood.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Thus began Miracle Messages. Its first project sought to reunite people with family and friends by posting videos on social media. With philanthropic support, it has grown more sophisticated. It takes referrals on a hotline, (800) MissYou ([800] 647-7968), and an online form. A stable of volunteer digital sleuths supported by a professional private investigator pursue requests from homeless people hoping to renew long broken ties and from family members seeking long-lost relatives.

Adler said the project has reunified about 800 families.

By 2020, Adler was experimenting with a buddy program at a residence for formerly homeless senior citizens when the pandemic foreclosed on in-person contact. The buddy system transitioned to the telephone.

“We found the relationships developed pretty quickly,” Adler said. “People opened up, became authentic friends.”

San Francisco’s then homelessness czar, Jeff Kositsky, invited Adler to the city’s shelters. Soon, 80 volunteers were making weekly contacts by phone and text.

The next phase came from feedback Adler got from volunteers who wanted to know if they could give their buddies a few dollars.

“You asked me to be a friend to this person, but they don’t know what they’re going to eat tonight,” they would tell him.

Adler didn’t want money to intrude on the volunteer relationship. But the idea of cash support appealed to him.

An appeal on social media raised $50,000. A pilot with 14 clients who received $500 monthly for six months proved promising.

They spent it on food, housing, storage fees and even charitable donations, Adler said, “totally at odds with what I think society would expect people experiencing homelessness to do with the money.”

Media coverage caught the attention of Scott Layne, a Los Angeles entrepreneur and philanthropist. Layne offered Adler seed money to expand the program to Los Angeles and provided seed funding that led to a $1.1-million grant from Google.org.

Adler, whose nonprofit has no physical headquarters in Los Angeles, hired two recruiters, Jenni Taylor, who worked for nonprofits in Cambodia and Peru before following her partner to Los Angeles, and John Ma, who left an executive job at Fox Corp. to pursue his love for street-level public service.

On a recent evening, they made one of their regular stops at JD’s Place, a shelter in South Los Angeles.

John Ma, right, seated, signs up Johnny Brock, a Bridge shelter resident, for the Miracle Messages program. Jenni Taylor, left, general manager of Miracle Messages Los Angeles, chats with resident Katrina Hobbs, who will be leaving the shelter soon with her husband for their own home.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

“Sometimes you need someone outside the people you see every day,” Taylor told a small audience of residents. “You need an outside perspective, someone to just listen, connect with. We’re going to match you with one person, and that one person is going to call you, check in on you and just be there. None of us are a trained therapist. We’re not a case manager. We don’t have housing vouchers. We’re really just a friend.”

Johnny Brock, who was several months out of prison, signed up that night. He said a German pen pal who befriended him in prison helped in his rehabilitation. He thought he could use a friend on the outside too.

One thing Taylor did not do was promise money. Not everyone who signs up for Miracle Friends will receive Miracle Money.

For research purposes, “friends” are divided into three randomized groups. A third of those who sign up will be held on a waiting list through the duration of the study. Of those matched with a phone buddy, half will be designated to receive $750 monthly for a year if they stick with the relationship for several months.

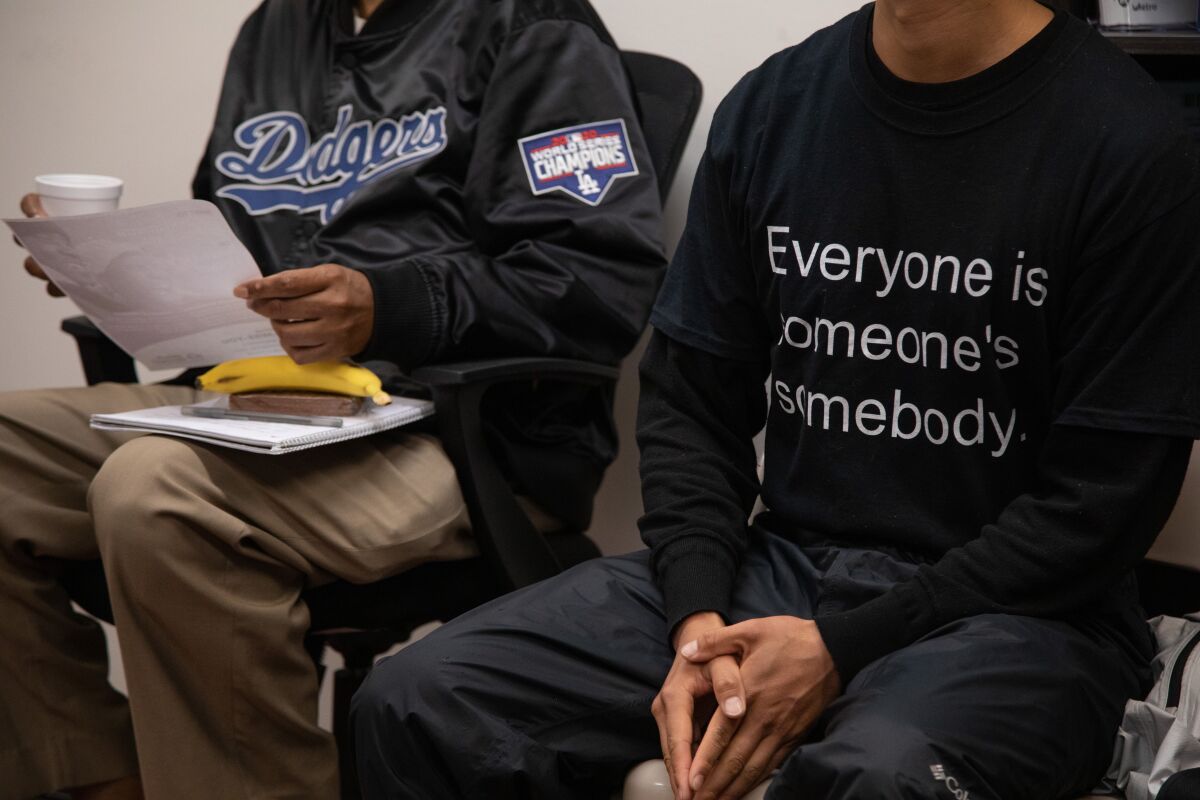

John Ma, right, with Miracle Messages, wears the company’s motto on his shirt while visiting JD’s Place, a city Bridge shelter.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

Not all do. Of about 350 recruits in Los Angeles, only about half have continued to stay in touch, said Ben Henwood, a professor in the Dworak-Peck school who is leading the study.

Daniel, who learned about Miracle Friends when Adler made a presentation at a Department of Commerce inclusion and diversity program, said she was immediately taken by the concept but got discouraged when several friends — all men — disappeared.

Thompson was her last try.

“We hit it off right away,” she said.

Now that she feels the friendship is secure, she worries about the money entering the fray.

“If she received this money would it be a setup or a setback?” she asked herself. “I didn’t want her to be able to receive the money for a year and when it cuts off she not be able to maintain.”

Henwood’s team surveys participants every three months to learn if having a friend improves mental health and whether a basic income can lead people out of homelessness. A formal report will come after 100 friends complete 15 months. Henwood said he hopes to have preliminary results by the end of the year.

Layne, the philanthropist who encouraged Adler to bring Miracle Friends to Los Angeles, said he sees the benefit already as a volunteer.

His friend, who asked that his name not be used, spent 25 years in prison for killing a friend while on an LSD trip and now lives in his car on the Westside and watches over his mother, who lives in her own car.

On a recent call their conversation drifted over a diversity of topics: great hiking spots, the alignment of the planets, the color of daisies and the number of bullets fired in the new “John Wick” movie.

The light talk was punctuated by a few delicately probing questions and long, revelatory answers.

“Did you ever talk to your parole officer about appealing that decision from the other month?” Layne asked.

“It’s like I’m tired,” the friend replied. “I see all these people getting off parole and I’m doing exactly what the parole board told me to do. They said, ‘Stay out of trouble. Take care of your mom. Keep doing good.’ That’s what I’m doing.

“I’m going to make sure, when my mom shuts her eyes, ain’t no one’s going to mess with her,” he told Layne. “She took care of me for the 25 years I was in, pretty much all of my life. Now someone has to take care of her, Bro.”

Layne said the relationship has deepened to the point he thinks it’s time they meet in person.

Thompson may never meet Daniel, but their relationship has definitely given her a boost.

A borderline diabetic, she’s using the money to catch the bus to a Starbucks and grab some groceries, real fruits and vegetables to substitute for the tiny home food provided at the tiny home community.

“I can’t always eat the food here because I have high blood pressure,” she told Daniel during their recent call. “I got to watch the salt intake.”

“I would say, ‘Watch the carbs,’ ” Daniel suggested. “The carbs, when you’re not working out and burning it, it turns into sugar.”

“I picked up bottles and cans the other day, just for the hell of it,” Thompson said. “It gives me something to do while I’m walking. You help the ground, you know. You help clean the area.”

The effort was paying off for her health-wise and she needed to do some shopping.

“My clothes are way too big for me,” she said.

“Let’s talk about the future, because you got a place,” Daniel said.

“As soon as I got those keys in my hand, I’ll take pictures and send them to you,” Thompson said.

“Yeah, because that’s going to be another blessing,” Daniel said.

Thompson thought of all those nights out in the cold, waking up to strangers standing over her.

“Oh, yeah, it’s a big blessing. I been waiting since 1999.”

This story originally appeared on LA Times