Acknowledging growing concern over the mistreatment of cannabis workers, California regulators have quietly assembled a team to pursue labor exploitation in the state’s burgeoning weed industry.

The new unit, housed within the Department of Cannabis Control, recently solicited help from law enforcement agencies statewide to investigate cannabis operators who coerce or threaten workers, subject them to hazardous conditions or deny them pay.

The April 13 bulletin, obtained by The Times, said the unit seeks to create a “central repository” of cannabis-related human trafficking investigations.

Its launch followed the December publication of “Dying for Your High,” a Times investigation detailing the plight of cannabis workers who are cheated, threatened with violence or sometimes die because of unsafe working conditions. The newspaper identified abuse allegations against nearly 200 cannabis farms or contractors — half of them licensed by the state— since legalization. It found 35 cannabis workers killed on the job in a five-year span, a death toll that has since risen to at least 37.

The story spawned a legislative town hall in March to gather information on exploitation in the cannabis industry, with the promise of further hearings this fall. It also has been taken up by others pushing for a centralized state agency to pursue labor trafficking investigations for workers in all industries. Though California banned human trafficking in all forms in 2005, a state watchdog agency found enforcement of the law is haphazard and often lacking, with no central agency for victims to turn to.

There is a growing awareness that California’s cannabis explosion — a dramatic escalation by both legal and unlicensed cultivators seeking to capitalize on the nation’s rapidly expanding weed markets — has put many workers in peril.

Sheriffs in five Northern California counties last year began training narcotics officers on human trafficking intervention. Initiatives by the state attorney general and the governor’s office to combat illegal cannabis operations are also billed as having the potential to disrupt human trafficking.

A remote cannabis operation deep in the Trinity County forest.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

For the state cannabis agency, which licenses and regulates commercial businesses, the new investigative squad is a step beyond, the first to tackle exploitation of cannabis workers specifically.

The Human Trafficking/Exploitation Assessment and Response Team — dubbed HEART — is based out of Fresno. Formed in March after months of discussion, it includes six detectives already in the field on other duties, a sergeant and an analyst.

It marks a notable expansion in the mission of the Department of Cannabis Control, which previously said it had never taken action against a state cannabis license holder for how it treated its workers and said that it forwarded worker complaints to state labor agencies.

A spokesman for the cannabis agency, David Hafner, said the sworn officers were now free to work cases and refer the results to prosecutors or federal agencies. The team is also poised to provide police training on trafficking investigations. Hafner would not provide further details or discuss outreach to crime victims or worker advocates. He said publicizing the crackdown on exploitation “would not deter crime” but would instead warn criminals to better conceal their activities.

The cannabis agency verified the squad’s existence only after The Times said it had obtained a copy of the bulletin.

It has refused to discuss its handling of worker exploitation since before September, when The Times published an expose on the state’s runaway illegal cannabis market. Lawmakers communicating with the department on ways to address worker exploitation said they were unaware of the new unit. The cannabis agency keeps no records of cannabis employment, including the size of the workforce.

Meanwhile, the known number of cannabis workplace fatalities continues to rise.

A cold snap in the Mojave Desert in late 2019 led to the deaths of two workers. Lucio Aguilar Rodriguez, 30, of Solano, Mexico, was found Dec. 29 inside an Adelanto greenhouse warmed by a gas heater. The air within the greenhouse was rank with exhaust fumes. An autopsy by the San Bernardino County coroner showed carbon monoxide poisoning.

A little more than a week later, a co-worker discovered the body of 18-year-old Rey de Jesus Antonio Osorio in a greenhouse near Lucerne Valley, poisoned by carbon monoxide from a generator.

As is the case with nearly all cannabis workplace deaths identified by The Times, the fatalities were not reported to state workplace safety officials. Carbon monoxide poisoning is the leading cause of death, claiming the lives of 22 workers.

With no organized outreach, the grievances of cannabis workers about substandard conditions and threats of violence often show up in California’s wage claims system, run by the Department of Industrial Relations. A labor official in March told lawmakers that case agents can refer allegations to a field enforcement division, but they are limited to enforcing work and hour laws.

Pending wage claims against a licensed Trinity County farm include photographs of freezing working conditions, with one worker reporting he sought shelter inside a steel shipping container, without access to drinking water, a bathroom or light.

In interviews, two workers told of laboring on the farm for 11 days behind a locked gate, under spartan conditions. They provided copies of work logs that showed as many as 21 workers who put in 13- to 14-hour days gathering the harvest. They shared videos of a makeshift work camp, with a single-burner propane stove for outdoor cooking, a wood pallet that served as the food prep surface, a portable toilet, and the shipping container where they worked during the day and some slept at night.

The container was unheated to protect cannabis that was to be fresh frozen, but workers said on the last two days, as temperatures fell below freezing, they secretly brought in a propane heater. According to interviews, the majority of workers were from Argentina, recruited by a compatriot who met them at a grocery store parking lot, then led them up the twisting dirt road.

The owner of that farm, Samuel Elias Schachter, made no reference to how workers would be accommodated on his remote 12-greenhouse farm atop Browns Mountain, files at the county planning office in Weaverville show.

But neither was there an expectation he should house those working on the 3,200-foot ridge, nearly an hour from town, his bookkeeper told The Times. It has long been common practice for cannabis workers in Northern California’s Emerald Triangle to sleep in their cars, or bring tents.

“I’m not quite sure why they’re saying they need housing,” said Jeannine Greenslade, who said she was asked by Schachter to respond to The Times’ questions on his behalf.

Nor did Greenslade see an issue with the padlocked gates on the long mountain road leading up to the farm. Cannabis operations, by their nature, require security, she said. “Anybody can come and go,” she said. “Nobody’s holding them.”

Workers interviewed by The Times said they did not know the padlock combinations. “No podíamos salir,” one worker said. We couldn’t leave.

“In our case, it’s not like [human] trafficking,” another said, “but we don’t like that they closed the gate … because we want to stay free.”

The first of several locked gates on the mountain road leading to Ratchet Construction. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Where Schachter’s bookkeeper and his workers most disagreed was the matter of pay.

Two workers from the 2021 season and four from 2022 allege they were promised payment after the harvest, and then were told there was only money enough for partial pay — as little as $900 for 117 hours work. The 2021 workers filed a federal civil suit seeking $160,000 in wages and damages. The 2022 claims were filed with the state labor department, and averaged $9,400 apiece. One of those claims was dropped, without details of how it was resolved.

“He has paid everyone,” Greenslade said, contradicting the workers’ signed statements that they are owed wages.

Schachter took the labor condition allegations seriously, said Greenslade. “We’re doing what we need to do legally to comply.”

She said, though, that California regulations in regard to cannabis cultivation workers were vague and contradictory. She said it was unclear, for example, if the bands of workers who move from farm to farm at harvest time are “employees” or “independent contractors” or, Greenslade said, “just trimmers.”

Weaverville, from where cannabis workers said a recruiter led them up mountain roads to an isolated farm.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Workers speaking to The Times said Schachter threatened to report them to federal immigration authorities, or castigated them.

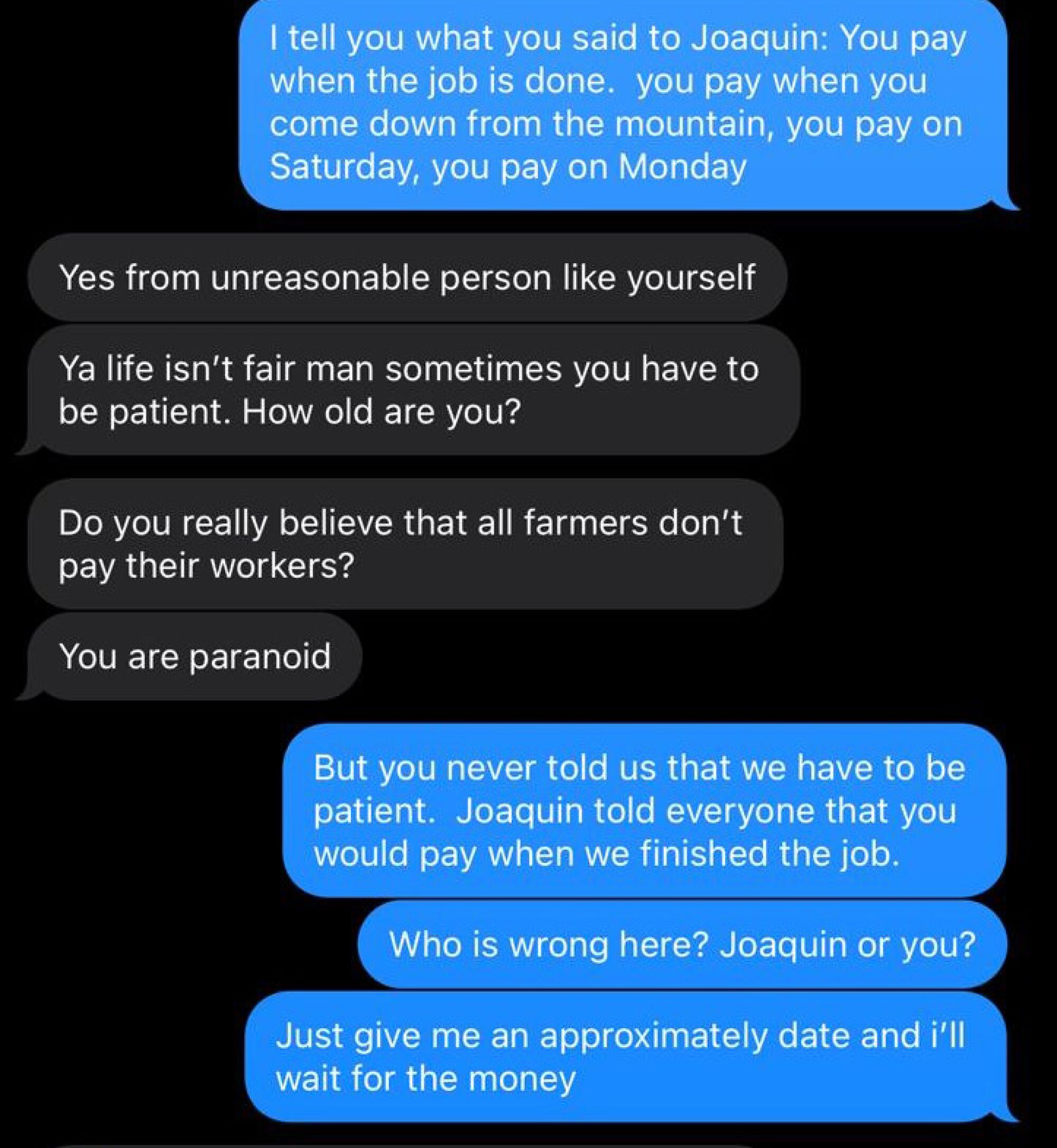

“You can play the victim all you want,” he told a worker in text messages shared with the newspaper. “No one is going to care that it’s taking longer than expected to get paid.”

Another worker who filed a federal civil suit against Schachter over wage claims described a similar exchange.

“He was like, ‘Come on, bring it on … nobody’s going to hear you,’” the worker told The Times. “‘Nobody’s going to help you to do that to me. Nobody’s going to listen to you.’”

In text messages, Schachter told a worker to “be patient” for his wages.

A criminal lawyer representing Schachter on unrelated domestic violence charges said he was unaware of the labor violation allegations.

That attorney, Thomas Ballanco, is himself a licensed cannabis grower and in separate matters is representing five workers who seek $105,000 in unpaid 2021 wages from a licensed operation in Hayfork. He said labor issues such as these are a facet of California cannabis’ long history of operating underground, hidden from the law.

“This is how employees were located, how they were treated and how they were paid,” Ballanco said. “Nobody wanted anybody to know anything. It was all cash. Nobody was on the books. …

“That’s not to excuse misbehavior,” he said. “It’s a partial explanation of why it’s so rampant.”

Lawmakers said the formation of a state cannabis exploitation team does not deter their own efforts to create a statewide labor trafficking division.

A bill by Assemblymember Joaquin Arambula (D-Fresno) would put that unit within the Department of Industrial Relations.

“Labor trafficking is a severe aggregated form of wage theft,” and because of that, Arambula said, many victimized workers already turn to the agency for help.

Gov. Gavin Newsom last year vetoed identical legislation, saying he preferred to see a labor trafficking unit within the state Civil Rights Department. Assemblymember Blanca Rubio (D-Baldwin Park) said she is working with Newsom’s office on a bill to do just that.

The Civil Rights Department typically handles only civil matters, such as workplace discrimination. In 2020 it was faulted by the Little Hoover Commission, the state’s independent watchdog, for failing to pursue labor trafficking investigations even when it had legal authority to do so.

The commission found that 15 years after California banned all forms of human trafficking, no agency was mandated to combat it, no data on trafficking were kept, and even departments authorized to pursue criminal cases did not do so. In its series of reports, the commission faulted the state for a scattered, “siloed” approach that focuses on sex trafficking, with little heed paid to workers across all industries exploited through force, fraud or coercion.

A worker’s photo at the licensed Trinity County cannabis farm where laborers described exploitative working conditions.

California closely regulates the environmental impacts of cannabis, but the Times investigation found worker protections were mostly relegated to labor unions, who negotiated a state requirement for cannabis farms with 20 or more workers to enter into contracts allowing organizers access to employees.

Those so-called labor peace agreements have largely left cannabis field workers unprotected, said Kristin Heidelbach, a labor lobbyist and organizer.

She sat on the state’s original cannabis regulation advisory panel and since legalization has dealt with workers in the field, first for the Teamsters, and now for the United Food and Commercial Workers union.

While there are exceptions, she described “evasive” cannabis employers who under-report the size of their workforce to skirt regulatory requirements. She said it was emblematic of cannabis’ underground culture, where growers historically distrusted authority and structure and who to this day sell on both legal and illegal markets.

“We’re still pulling this industry into the light,” she said.

Immigrant cannabis workers like this one say they endure substandard conditions and exploitation.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Many immigrant workers live on the margins and have little choice than to labor on farms that provide few safeguards from outside threats, let alone bathroom facilities and lunch breaks, Hernan Hernandez, executive director of the California Farmworker Foundation, said at the March town hall.

“Everything that we as a society have built for our workforce,” he said, “goes out the door the second they step onto these cannabis grows.”

This story originally appeared on LA Times