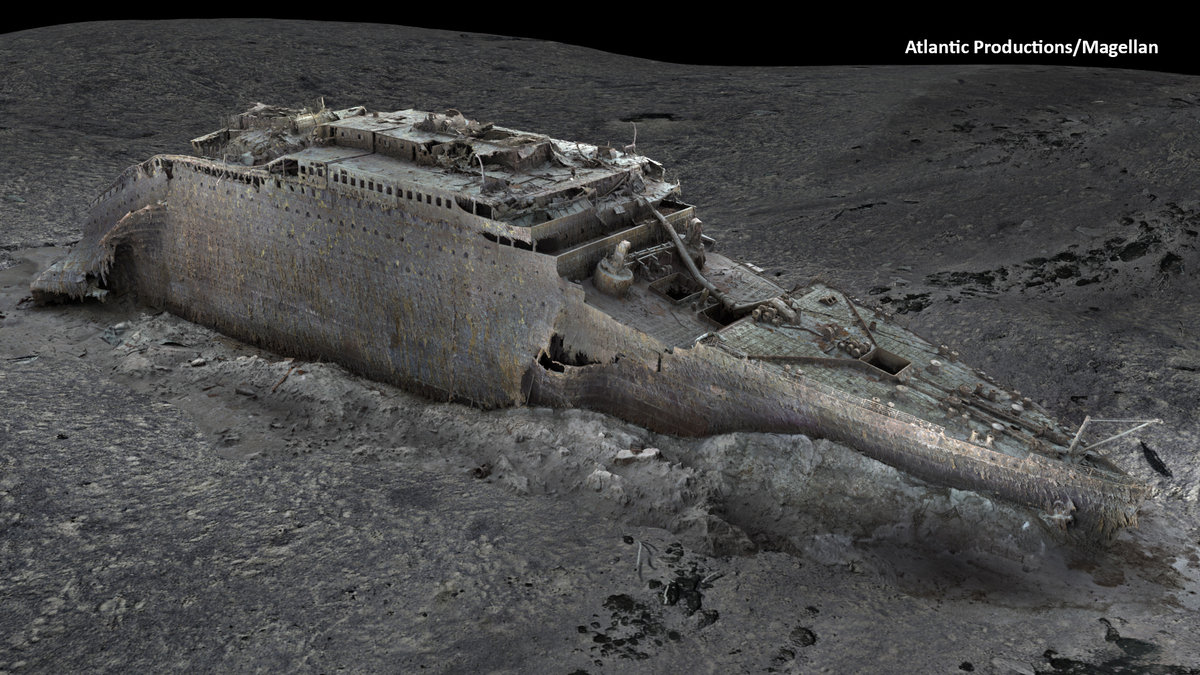

Scientists were able to map the entirety of the shipwreck site, from the Titanic’s separated bow and stern sections to its vast debris field.

Atlantic/Magellan

hide caption

toggle caption

Atlantic/Magellan

Scientists were able to map the entirety of the shipwreck site, from the Titanic’s separated bow and stern sections to its vast debris field.

Atlantic/Magellan

A deep sea-mapping company has created the first-ever full-sized digital scan of the Titanic, revealing an entirely new view of the world’s most famous shipwreck.

The 1912 sinking of the Titanic has captivated the public imagination for over a century. And while there have been numerous expeditions to the wreck since its discovery in 1985, its sheer size and remote position — some 12,500 feet underwater and 400 nautical miles off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada — have made it nearly impossible for anyone to see the full picture.

Until now, that is. Using technology developed by Magellan Ltd., scientists have managed to map the Titanic in its entirety, from its bow and stern sections (which broke apart after sinking) to its 3-by-5-mile debris field.

The result is an exact “digital twin” of the wreck, media partner Atlantic Productions said in a news release.

“What we’ve created is a highly accurate photorealistic 3D model of the wreck,” 3D capture specialist Gerhard Seiffert says. “Previously footage has only allowed you to see one small area of the wreck at a time. This model will allow people to zoom out and to look at the entire thing for the first time … This is the Titanic as no one had ever seen it before.”

The Titanic site is hard to get to, hard to see and hard to describe, says Jeremy Weirich, the director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Ocean Exploration program (he’s been to the site).

“Imagine you’re at the bottom of the ocean, there’s no light, you can’t see anything, all you have is a flashlight and that beam goes out by 10 feet, that’s it,” he says. “It’s a desert. You’re moving along, you don’t see anything, and suddenly there’s a steel ship in front of you that’s the size of a skyscraper and all you can see is the light that’s illuminated by your flashlight.”

This new imagery helps convey both that sense of scale and level of detail, Weirich tells NPR.

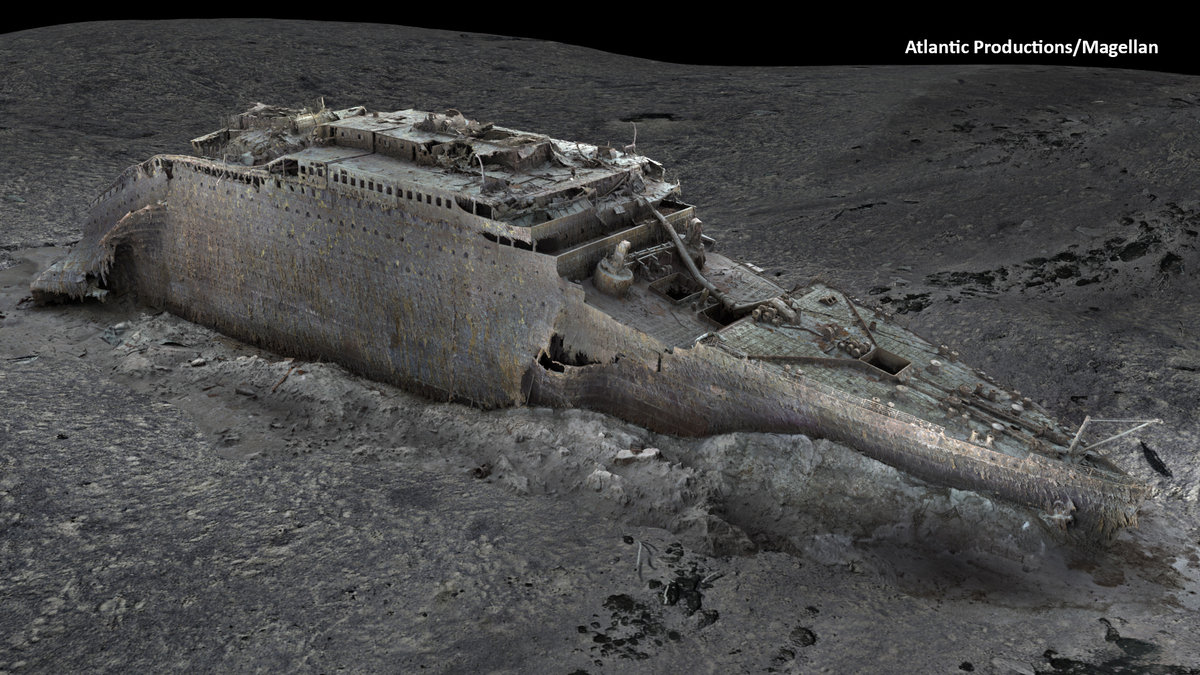

Magellan calls this the largest underwater scanning project in history: It generated an unprecedented 16 terabytes of data and more than 715,000 still images and 4k video footage.

“We believe that this data is approximately ten times larger than any underwater 3D model that’s ever been attempted before,” said Richard Parkinson, Magellan founder and CEO.

Experts in Titanic history and deep-sea exploration are hailing the model as an invaluable research tool. They believe it could help scientists and historians solve some of the ship’s lingering mysteries — and learn more about other underwater sites, too.

Longtime Titanic explorer and analyst Parks Stephenson described the model as a “game changer” in a phone interview with NPR.

“It takes [us] further into new technology that’s going to be the standard, I think, not just for Titanic exploration, but all underwater exploration in the future,” he adds.

The effort yielded 16 terabytes of data and more than 715,000 still images, in what Magellan calls the largest underwater scanning project ever.

Atlantic/Magellan

hide caption

toggle caption

Atlantic/Magellan

The effort yielded 16 terabytes of data and more than 715,000 still images, in what Magellan calls the largest underwater scanning project ever.

Atlantic/Magellan

A project years in the making, featuring Romeo and Juliet

Explorers and artists have spent decades trying to depict the Titanic wreck, albeit in lower-tech ways.

After Robert Ballard — along with France’s Jean-Louis Michel — discovered the site in 1985, he combined all of his photos to form the first photomosaic of the wreck, which showed the ship’s bow and was published in National Geographic. Those efforts have been replicated in the years since.

“But the problem with all that is it requires interpretation,” Stephenson says. “It requires human interpretation, and there are gaps in the knowledge.”

Flash forward to the summer of 2022. Scientists spent six weeks capturing scans of the site, using technology that Magellan says it had been developing over the course of five years.

The expedition deployed two submersibles, named Romeo and Juliet, some 2.3 miles below the surface to map every millimeter of the wreck site.

They didn’t go inside the ship, let alone touch the site, in accordance with existing regulations, and paid their respects to the more than 1,500 victims with a flower laying ceremony.

And they describe the mission as a challenge, with the team fighting bad weather and technical challenges in the middle of the Atlantic.

“When we saw the data come in it was all worth it,” Seiffert says. “The level of detail we saw and recorded was extraordinary.”

The scientists spent months processing and rendering the data to create the “digital twin,” which the company says it’s looking forward to sharing publicly.

Stephenson saw an early version of the model, when Atlantic Productions brought him on to consult on its validity. So did Ken Marschall, the maritime artist known for his Titanic paintings.

“We’ve both seen it with our eyes. We’ve both seen thousands of digital images of the wreck in imagery, moving imagery,” Stephenson said. “But we’d never seen the wreck like this. It was different, but at the same time you just knew it was right.”

Experts say the model will be a valuable tool for future Titanic research and deep-sea exploration in general.

Atlantic/Magellan

hide caption

toggle caption

Atlantic/Magellan

Experts say the model will be a valuable tool for future Titanic research and deep-sea exploration in general.

Atlantic/Magellan

There’s still a lot left to learn about the Titanic

Can there really be that much left to discover about the Titanic, more than 110 years on?

Stephenson says “at the end of the day, none of this matters.” But there’s a reason people keep visiting and talking about the wreck, he adds, and it’s not because of any buried treasure.

“It’s fame, I guess,” Stephenson says. “People can’t get enough of Titanic. And as long as people can’t get enough of the Titanic, people will keep going to … these mysteries.”

In Stephenson’s case, it’s the unanswered questions that keep drawing him back.

“I’ve been grinding away at this for a while, and I’m not on a crusade to dismantle the Titanic narrative that has grown since 1912,” he says. “But … I have had enough experience and seen enough evidence that makes me seriously question even some of the most basic aspects of the Titanic story.”

One example: Stephenson says there’s reason to doubt the long-accepted conclusion that the ship hit the iceberg along its starboard side. He points to a growing body of evidence that suggests it actually grounded briefly on part of the iceberg that was submerged underwater instead.

Just looking at the preliminary modeling has helped Stephenson bring a lot of his evidence and questions into focus — it may be early days, but he says he already has a better understanding of how the ship’s stern came to be in such bad shape.

Stephenson sees this moment as a paradigm shift in underwater archaeology.

“We’re essentially getting to the end of the first generation of Titanic research and exploration, and we’re getting ready to transition into the next generation,” he says. “And I think this tool basically signals a shift from that generation to the next.”

Stephenson wants to use the model to document the extent of Titanic exploration up to this point, from Ballard to James Cameron and beyond. He says a “massive project” is underway, and will hopefully result in a scientific paper and online archive. Then, he plans to use the tool to answer whatever questions remain.

There have been “photomosaics” and other renderings of the shipwreck over the decades, but this is the first such 3D model.

Atlantic/Magellan

hide caption

toggle caption

Atlantic/Magellan

There have been “photomosaics” and other renderings of the shipwreck over the decades, but this is the first such 3D model.

Atlantic/Magellan

The Titanic is a gateway into deep ocean exploration

As a maritime archaeologist, Weirich is most interested in what the ship’s condition can teach us about how to better preserve deep-sea shipwrecks in general. For example, how has it impacted the environment since it sunk, and how have the visits since its discovery impacted the site?

The Titanic site has been designated as a maritime memorial, which makes preservation even more important. And Weirich says research on everything from its rate of deterioration to the microbial environment can be applied to other such sites worldwide.

There are estimated to be hundreds of thousands of wrecks in the world, from ancient wooden ships in the Black Sea to World War II vessels in the Gulf of Mexico, Weirich says.

And this kind of technology could play a crucial role in learning more about deep-sea environments in general, from undersea resources to geological features to unknown species.

Weirich says he hopes these images of the Titanic will give people a greater appreciation for the deep ocean, and a better understanding of just how much is left to explore.

“The story of Titanic and the shipwreck itself is extremely compelling, but it is a gateway for people to understand what we know and don’t know about the deep ocean,” he adds.

Weirich remembers being personally captivated by those first images of the shipwreck in National Geographic when he was just 10 years old. That sparked his lifelong interest in ocean exploration — and he hopes young people seeing these latest images are inspired too.

This story originally appeared on NPR