In Turkey, politics is complex, sensitive and divisive – and if you want to know what that looks like, there’s no better place to witness it than a market stall in the bustling city of Bursa.

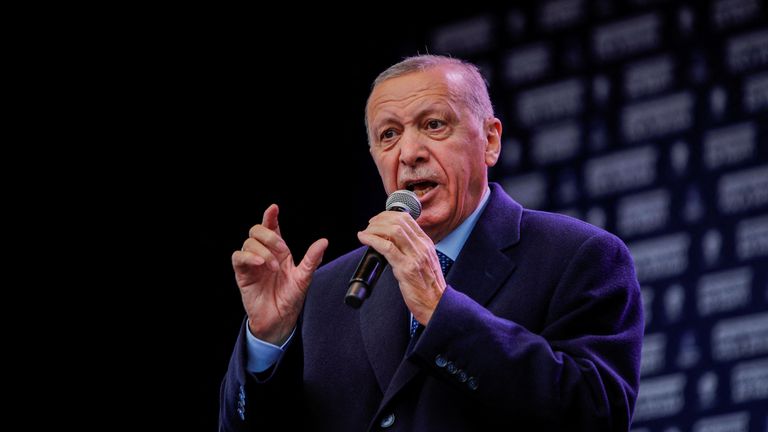

We’re here asking people about Sunday’s election, when Recep Tayyip Erdogan will seek to extend his two-decade-long grip on power. And here, among the colours and fragrances of the food stalls, many like him.

“He is a good leader, I’ll be voting for him,” says one man. Another tells me he would vote for Mr Erdogan 10 million times over, if only he could. A third says Mr Erdogan has made Turkey into a great country and stood up to America.

It’s all smiles until we ask one young man, who admits he’s unhappy with the economy, that prices are rising too fast, and that he’ll vote for someone else. No sooner are the words out of his mouth than a man rushes up to us and starts shouting. The scent of dissent has proved combustible. The atmosphere had changed.

We are, it seems, now guilty of meddling where we don’t belong. “We have a good leader, we don’t need anyone different,” the man says. He tells us we’re provoking trouble and then, stridently, he orders us to go away. Alongside him, a woman is also giving us an earful. Foreign journalists, asking questions.

In this country, Mr Erdogan is the great divider. You cannot be indifferent about him, and nor can you ignore him. His presence is everywhere, for he has personally reshaped the economy, the political system, the judiciary and the media. And, for good measure, there are posters of him all over the place.

But his hold on power may be weakening. On Sunday, Turkey will go to the polls to elect a new president, as well as vote for its parliament. It will be close but Mr Erdogan, after 20 years in charge, is now facing the significant possibility of a defeat that could have seismic repercussions.

Pitched against him is a group of opposition parties who have coalesced around one single aspiration – to dump Erdogan from power. And leading that coalition is Kemal Kilicdaroglu.

That’s why we’re in Bursa – to meet Mr Kilicdaroglu. The man who wants to reshape Turkey.

Read more:

Recep Tayyip Erdogan: Who is Turkey’s president?

The polar opposite of Erdogan

Mr Kilicdaroglu is finding international fame at the age of 74. He positions himself as the polar opposite of Mr Erdogan – a quiet man who seeks consensus, so the story goes, rather than an abrasive bombast.

We meet in the relative peace of his bus. Through the window, he can see thousands of people gathering to hear him speak and holding posters of his face. We shake hands and sit down. Mr Kilicdaroglu, who does not speak English, is smiling broadly.

I point to the people gathering outside. Is expectation becoming a burden?

“I am not the only one who feels the pressure,” he replies. “If hundreds and thousands of people have come together, it is to react to the pressure because there are serious problems in the economy and these problems make society restless.”

But does he really want to be president, or does he simply want to thwart Mr Erdogan, I wonder.

“There is real damage inflicted on the founding pillars of the country,” he insists. “The main pillars of democracy, which are the legislature, the judiciary and the executive, are also seriously damaged. We want to fix this. I want to be the president and I really want to make Turkey a democratic country.”

‘Damage report’

He says that, if elected, he will spend a month compiling a “damage report” on his country. “We do not know what our earnings are, what our costs are, what our liabilities are.” It is a picture of misrule that he paints repeatedly – of a country that has become subsidiary to the interests of its leader.

Even if he does win, it will be by a slender margin. Mr Erdogan remains popular, often wildly so, with many in this country, particularly those who think Mr Kilicdaroglu is beguiled by the secular countries of the West.

So, after two decades when his country has become ever more distanced from Europe, Britain and America, how does Mr Kilicdaroglu plan to redefine Turkey’s place in the world? It is the question that has bothered leaders and diplomats for months now.

“We want to be a part of the West and the civilized world,” he tells me. “We want democracy in our country. We do not want an authoritarian leadership, we want freedom. Young people and women are fed up, they also want freedom.

“Therefore, we will be implementing all the democratic rules of the European Union to our country. Our relationship with the West will develop in a democratic way. Our ties will be even stronger. We will maintain our relations with Russia as they were in the past because many Turkish businessmen have investments there. But we are against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and we do not find it acceptable.”

I ask him if Turkey would change its stance on NATO if he wins – would he reverse Mr Erdogan’s objections and allow Sweden to join? “It will happen,” comes the reply.

Erdogan ‘is already playing dirty tricks’

The election is now within touching distance. There are persistent rumours of Mr Erdogan using the apparatus of the state to either manipulate the result or intimidate voters. So is Mr Kilicdaroglu worried about “dirty tricks”?

“He is already playing dirty tricks. I have never seen a man do this as much as he does in my life. He distorts the facts and slanders. But whatever he does, the people will choose me.” He doesn’t accuse him of corruption but says Mr Erdogan “is very fond of money”.

The latest polls have Mr Kilicdaroglu predicted to win around half the vote, potentially enough – just – to give him an outright victory in the first round.

‘I will be the president for all of Turkey’

It would be an extraordinary result, but also a towering challenge – to unite his nation, repair the economy, restore the structures of democracy, reconnect with bruised allies and somehow bridge the chasm to Mr Erdogan’s voters.

“I will be the president for all of Turkey, for all 85 million people,” he says. But what of those who don’t like him, I ask. “If there is a good leadership, no looking down on people, and you treat all citizens equally, and if you bring justice to all who seek justice, if the state is transparent, if you’re able to account for all the taxes collected, they will see what a good leader is, they will come to our side.”

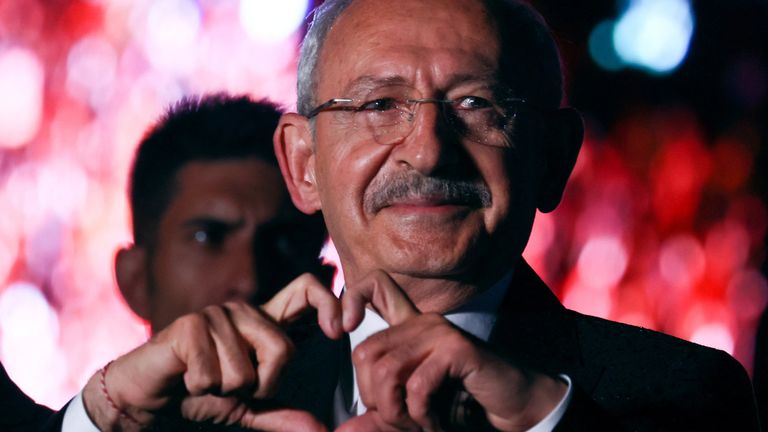

Our time is up. A huge crowd waits for him and, shortly, he will bound on to the stage and make his familiar sign – a heart shape made with his two hands. But for the moment, he simply thanks us and shakes hands. “Will you win on Sunday?” I ask, as we walk. “Oh yes,” comes the reply. And he smiles, broadly.

This story originally appeared on Skynews