The stock-market panic over the regional banks has subsided for now, but experts say that regulators should remain focused on shoring up the stability of the sector amid economic headwinds that could persist for years to come.

Shares of regional banks like PacWest Bancorp Corp.

PACW,

have rebounded in the past week following news that their deposit bases had stabilized, with the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF gaining nearly 15% from its early March lows.

Richard Portes, a London Business School economist and an expert on financial stability, said in an interview with MarketWatch that the same economic headwinds that helped catalyze the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank remain.

“Funding costs for regional banks took a big jump a couple of months ago and they haven’t come down,” Portes said, noting that the spread between the interest rate regional banks must pay to borrow money in the debt markets and the rate large, diversified banks pay has widened significantly of late.

Meanwhile, banks of all sizes must increase the rates they pay depositors to compete with other savings vehicles like money market mutual funds. Deposits are typically a bank’s cheapest form of funding, but they are proving to be less stable than in past eras, according to Portes.

“Regional banks own all these long-dated assets, whether they are mortgages or longtail securities that are not paying anywhere near those funding costs,” he added. “That’s a really big deal.”

BondCliq

The chart above shows the average difference in yield between 10-year Treasury bonds and 10-year debt issued by major regional banks including Citizens Financial Group Inc.

CFG,

Comerica Inc.

CMA,

Fifth Third Bancorp.

FITB,

PacWest and Western Alliance Bancorp.

WAL,

Borrowing costs for these banks rose sharply following the Silicon Valley Bank failure and again as First Republic Bank began showing signs of stress. They have come down from recent highs, but remain elevated compared to the start of the year and compared to large diversified banks perceived to be too-big-to-fail.

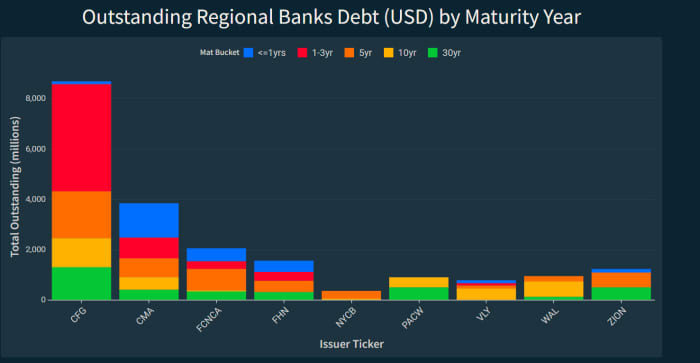

Several regional banks that have found themselves at the center of market skepticism towards the sector also have significant amounts of debt scheduled to mature in the next 1-3 years, which may put further pressure on the sector as it seeks to replace this funding.

BondCliq

Economists estimate that the market assets of the U.S. banking system are worth more than $2 trillion less than the book value of those assets. Banks are allowed to value securities that they plan to hold to maturity at their face value rather than their market value, which can disguise losses in a rising-interest rate environment. Bonds issued during a period of low interest rates lose value as rates rise.

Such accounting rules help lessen volatility in bank earnings and can provide a more accurate picture of profitability during normal times, but Portes argued that regulators should be looking closely at the market value of bank assets during times of stress.

A new variable for regulators to consider is the speed with which runs on Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank occurred, according to Karen Petrou, co-founder of the banking advisory firm Federal Financial Analytics, Inc.

“The most radically new lesson of the recent crisis is the vulnerability of banks to viral runs,” she said, noting that new technology has enabled panic to spread much faster than in previous eras, carving out a new terrain for regulators to navigate.

Researchers led by economist Luigi Zingales of the University of Chicago published an analysis in April that showed that banks with well-functioning mobile applications experienced greater deposit flight when the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates than those without those digital tools.

This new dynamic makes it ever more important that federal and state bank supervisors aggressively monitor bank liquidity and risk-management practices during periods when rising interest rates incentivize depositors to move their money from traditional banks to higher-yielding investments.

Banks began seeing a slow-moving drain on deposits as early as the second quarter of 2022, Zingales noted, which he labeled a “bank walk” in contrast to the rapid run on deposits that occurred at several banks earlier this year.

“It is clear that deposits have become much less sticky,” he wrote. “This is not a problem if…banks do not have large losses in their held-to-maturity assets or in their loan portfolio. If they do, however, this mobility will slowly expose losses that the banks cannot face.”

Petrou said that these new realities mean that Congress should increase deposit insurance for business transaction accounts and regulators must get serious about improving bank supervision and becoming much more assertive when they see behavior that could lead to worries about bank solvency.

“There were quite a lot of opportunities for regulators to step in and turn these failed banks around,” she said. “We’ve got to have much better supervision.”

This story originally appeared on Marketwatch