Mired in a sex scandal, Silvio Berlusconi held a dinner party at a posh Rome hotel in 2010 to charm reporters – but struggled to play it straight: “You’re all invited to the bunga bunga!” he told us defiantly.

Then the impish smile. “But you’d be disappointed.”

When it came to entertainment, Berlusconi – the media mogul-turned-prime minister, his hair slicked back and face orange from a fake tan – rarely disappointed. When it came to governing, he disappointed many parts of his country.

Yet upon leaving office a year after that dinner, never to return to power, the Milanese magnate left behind an enduring political legacy – and leadership vacuum – that affects Italy more than a decade later.

Over the course of his life and political career, Berlusconi, who died on Monday at the age of 86, was many things: a cruise-ship crooner, a media entrepreneur, Italy’s richest man, and its longest-serving postwar leader.

Above all, he was a larger-than-life figure who polarised modern Italian society and politics like few before him. He summed it up himself once when he said: “50% of Italians hate me, 50% love me”.

He revolutionised Italian politics and went on to dominate it for 20 years.

A conservative prime minister, he pioneered a brand of populism that took hold in other countries long after he had lost power, using wealth, fame and fierce rhetoric to gain power, much as Donald Trump was to do years later.

Berlusconi lived an unapologetically lavish life. In AC Milan, he once owned one of Europe’s most successful football teams. He used his media empire to hobnob with celebs and sustain his political career. Twice divorced, he was often seen with women decades younger than him.

“The majority of Italians in their hearts would love to be like me and see themselves in me and in how I behave,” he once said.

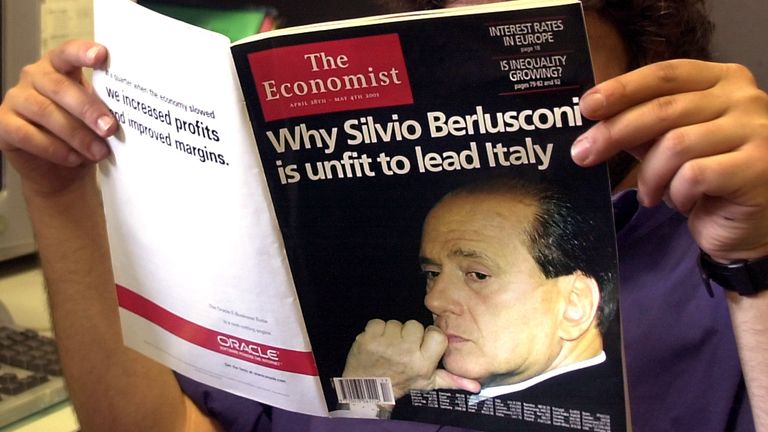

‘Unfit to lead’?

Berlusconi took advantage of the vacuum created by the corruption scandals of the early 1990s, which wiped out an entire generation of politicians, to launch his political career.

His critics said he wanted to save his business interests, which had been protected by politicians who were now disgraced and had lost power.

They saw him as a threat to democracy, a dangerous man who amassed unparalleled political and media power for a Western country.

The Economist famously deemed him “unfit” to lead the country, infuriating Berlusconi when he was trying to burnish his international credentials.

He called himself the “chosen one” to come to Italy’s rescue and save it from communists.

And he elicited worship among his admirers, who loved his can-do attitude, plain-speaking and break with the traditional political establishment.

Longest-serving prime minister

In a country that traditionally distrusts its political class, he was an outsider who promised Italians a dream, or “a new economic miracle”, as his early electoral slogan put it.

Over and over, Italians believed him: he was prime minister for nine years over three periods of time between 1994 and 2011 – longer than anybody since World War II.

In his prime, the perennially tanned Berlusconi – who in old age was surgically enhanced and had thicker hair thanks to a transplant – was a formidable and charismatic campaigner who defied the odds to keep coming back to power.

Berlusconi said his success in life was down to three things: “work, work and work”.

But he was also a crowd-pleaser who loved a joke and a party, did not shy away from the occasional singing at discos, and often boasted of his success with women.

Eventually he resigned in shame in 2011, weakened by the “bunga bunga” scandals and overwhelmed by the scale of Europe’s debt crisis.

In between those turbulent years, there were plenty of gaffes, sexist comments and racist remarks.

He described a newly elected Barack Obama as “young, handsome and tanned”; was reported to have used a vulgar term to describe Angela Merkel as sexually unattractive – and once at an EU summit kept her waiting while he was on the phone; likened a German politician to a Nazi concentration camp guard; said it is “better to be fond of beautiful girls than to be gay”.

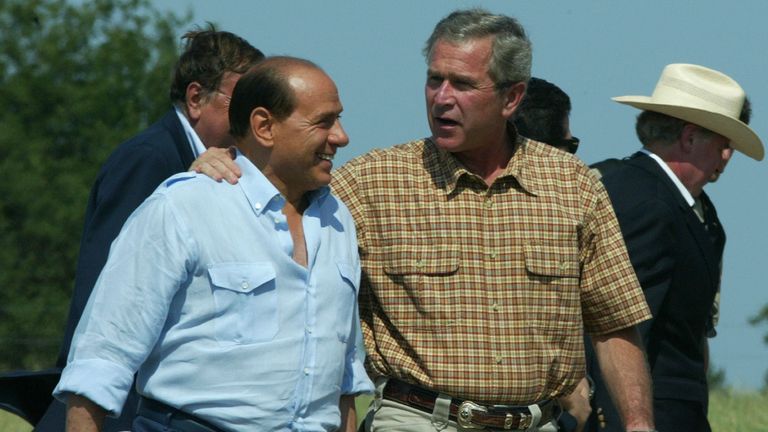

Berlusconi took controversial decisions, first and foremost going to war in Iraq in 2003 alongside George W Bush and Tony Blair, a move the majority of Italians opposed.

He played host to Muammar Gaddafi and his entourage, and was a close ally and friend of Vladimir Putin, hosting him in his Sardinian villa.

Even after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he struggled to distance himself from Putin, saying there would be no war if Volodymyr Zelenskyy had “stopped attacking the two independent republics of the Donbas” and adding that he judged the Ukrainian leader “very very negatively” and would not meet with him if he were still the Italian prime minister.

Legal cases

For years, Berlusconi managed to survive scandals that would have ended the career of many a politician – conflict-of-interest accusations, claims of corruption, even criminal trials.

He was convicted for tax fraud; and later of paying a minor for sex and abuse of power as part of the sex scandal – a conviction that was subsequently overturned.

He was even expelled from parliament and barred from public office, but the ban was lifted in 2018.

Throughout, he denied any wrongdoing, saying he was the victim of a political vendetta by left-leaning magistrates.

Berlusconi repeatedly made laws to protect himself and his business empire. But he shrugged off all controversy.

“All citizens are equal before the law, but maybe I am a little more equal than the others since I’ve received the mandate to govern the country,” he said, with an Orwellian twist, during a court appearance at one of his trials in Milan in 2003.

‘Bunga bunga’ parties

Ultimately, he engulfed Italy in a lurid scandal of sex and late-night “bunga bunga” parties that brought incalculable damage to the international reputation of the country and ridicule across the globe.

Between 2009 and 2010, when he was prime minister, Italian newspapers were filled with tawdry details of parties featuring scores of young women.

It started with revelations he had attended the birthday party of an 18-year-old who called him “Daddy”; it continued with tales of high-end escorts, accusations of underage girls being paid for sex; and of young women dressed as “sexy Santas” or pole-dancing for Berlusconi and his friends.

In one famous case, a 17-year-old Moroccan girl nicknamed Ruby Rubacuori (or “Ruby the Heart-Stealer”) was released from police custody after Berlusconi intervened with authorities – with his allies telling parliament that she was believed to be the niece of the late Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak.

Berlusconi has always maintained the “bunga bunga” parties were simply “elegant soirees” where nothing unsavoury went on.

“The parties were elegant and proper, the rooms were filled with guests and waiters”, he told journalists gathered at the hotel in Rome on a warm April night in 2010.

“We could even have shot the whole thing on camera, there was nothing to hide”.

One more comeback?

In the latter years of his life, Berlusconi was set back by a series of health issues, including open heart surgery in 2016, when he was 79.

He contracted COVID during the pandemic and became seriously ill.

He later described the illness as the “worst experience of my life”, and urged Italians to wear masks and maintain social distancing.

He was admitted to hospital again shortly before his death for chronic leukemia.

Berlusconi tried one more comeback in 2022, making an unlikely, and ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to become president. While the role is largely ceremonial, the president is seen as a figure of high moral standing who stays above the political fray.

But he did win a Senate seat at last year’s election, returning to parliament for the first time in almost a decade, with his Forza Italia party becoming part of the governing coalition supporting Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

Legacy

In many of his views and remarks, Berlusconi sounded like a dinosaur.

Yet he was in a way ahead of his time: a Trumpist tycoon who offended his way to success, who considered self-interest to be the national interest, and who employed charisma and TV marketing to shatter the norms of politics, and disorient his opponents.

Whether Berlusconi is remembered for his success or for greed; whether for charm or vanity; whether for ending the old corruption or just making it his own, he left an indelible mark on the Italian story.

This story originally appeared on Skynews