On a corner lot just off the 10 Freeway in Redlands, Slow Bloom Coffee Cooperative looks like any other hipster café.

Outside, planters made from repurposed wine barrels and galvanized sheet metal hold succulents. The Progress Pride flag — the banner with a triangle canton on the left side over a rainbow field to represent the trans community — flies from a pole next to the parking lot.

A bench next to a cactus garden offered relief to a line of customers that already stretched out the door. Above them, a marquee announced Slow Bloom’s name in festive, ‘60s-style font out of an Austin Powers movie.

Inside, cabinets and shelves were stocked with T-shirts, roast blends and store stickers. R&B played on speakers. Only a small display of framed newspaper articles next to the all-genders restroom hinted at a deeper story.

Stickers at the Slow Bloom Coffee Cooperative, a coffee shop, on July 11 in Redlands.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Slow Bloom is the culmination of a years-long struggle by former employees of Augie’s Coffee, a beloved Inland Empire chain that shut down in the summer of 2020. Father-and-son owners Andy and Austin Amento blamed the COVID-19 pandemic, but workers claimed the closure happened because they had formed a union.

The workers filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board, which ruled that the Amentos’ actions were illegal. That led to a financial settlement with the fired employees, most of whom had moved on to other jobs. But 15 had stuck together, selling cold brews and roasts online and at popups with dreams of opening their own shop.

With settlements in hand and tens of thousands of dollars in Kickstarter funds gathered by fans, the remaining Augie’s alumni opened Slow Bloom last spring as a worker cooperative — one of just a few such spots in the U.S. coffee industry. Everyone has an equal ownership stake, everyone has a say in every decision. Everyone makes $19 an hour and shares in the tip pool. They distribute any profits among themselves at the end of every quarter according to how much each person worked.

So far, so great.

Slow Bloom just opened a permanent popup at a local bar, is looking to rent a space to expand its roasting capabilities and is in talks with a baker to open another co-op in town. On the morning I visited, patrons of all ages and races came in and out and lingered in a shaded patio despite the already stifling heat.

The main room of Slow Bloom Coffee Cooperative, a coffee shop in Redlands. Former employees of Augie’s Coffee, a beloved Inland Empire chain that shut down in the summer of 2020, opened Slow Bloom as a worker cooperative.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

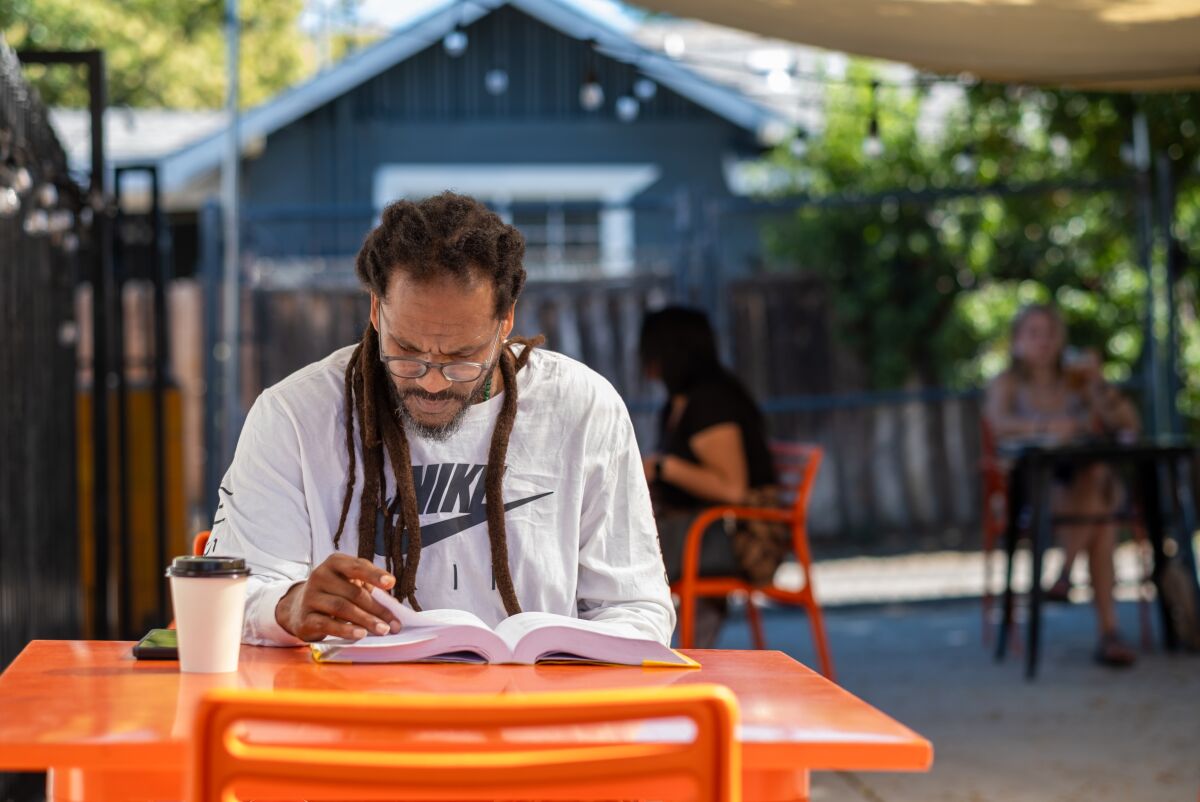

Daawud Smith enjoyed a double chai cut with oat milk as he read a self-help book. The San Bernardino resident had started hanging out at Slow Bloom a few weeks earlier, drawn in by the “positive vibes” of the place. At some point, he read the articles on the wall and learned about the café’s history.

“I think it’s great,” Smith said. “Don’t complain. Create and change. Go forward and do something better.”

A table over, Loma Linda University student Julius Reyes worked on a paper and shouted out Slow Bloom’s “ambiance, which is helping me with my creative juices.” A friend had told him about the store’s origins.

“It’s a very inspiring story,” said Reyes. “They took their own initiative to do that.”

Toward the back, Slow Bloom’s executive board — president Kelley Bader, vice president Jina Edwards and treasurer Evan Costello — sipped on their own brews and beamed.

“We caught the wave at a very good moment to ask people to help,” said Costello, 27. “People were so fed up with so much. People were ready for something new.”

“We’re still learning as we go, but there’s a sense of huge accomplishment,” said the 43-year-old Edwards. “But I feel ecstatic working here, because we come from the same place, and we’re in charge of our lives.”

Bader typed away on his laptop and searched for an email he had sent to one of the few other coffee cooperatives — a chain in the Sacramento area. “Every day, I wake up and think, ‘How did we get here?’ for better or worse,” said the 31-year-old. “But really, better.”

Slow Bloom’s executive board includes, from left, president Kelley Bader, 31; vice president Jina Edwards, 43; and treasurer Evan Costello, 27.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

I covered the closing of Augie’s in 2020, and the story always stuck with me even though coffee ain’t my cup — I’m more of an Orange Bang! type of guy. At the time, only a handful of coffee shops had unionized in the U.S., even though labor groups had been trying for decades. Experts felt it was an impossible task because barista-ing was seen as a transitory job drawing people who were looking for a workplace vibe instead of a living wage.

Over the past three years, however, coffee shops big and small have voted to unionize — over 300 Starbucks locations alone. Slow Bloom’s decision to run as a worker cooperative made them pioneers once more.

Bader said the fired Augie’s workers discussed early on whether to form a collective or open Slow Bloom as a traditional limited liability corporation, where only a handful of people would legally own it.

“We couldn’t employ 60 people just like that, and people needed to work immediately,” he said.

“But what were we fighting for?” Edwards replied. “We were fighting for autonomy. We wanted to all be on the same playing field, so no one would be overlooked.” She said the workers who ended up forming Slow Bloom took solace from longtime customers who supported them from the moment they were fired by continuing to buy their products.

“People would say, ‘Keep going, we’ll be here for you,’” Edwards said. “’We see you.’”

Worker cooperatives remain rare in this country. A 2021 United States Federation of Worker Cooperatives report estimated there were about 1,000 such businesses — a speck of the estimated 33 million small businesses nationwide. Slow Bloom is believed to be the only coffee shop run as a co-op in Southern California (another such effort in Lynwood closed a few years back).

Barista Jacob Rivera, middle, is a member and owner at Slow Bloom Coffee Cooperative. Each worker has an equal ownership stake, has a say in every decision, makes $19 an hour and shares in the tip pool.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Bader, Costello and Edwards think more coffee shops should follow in their steps. They’re now the ones offering advice, even as they continue to ask others for it.

“It’s a lesson in commitment,” Costello said. “It’s been like building a car while the engine is driving it forward.

The problems they have faced in their new venture are nothing they hadn’t experienced before at Augie’s. The first week, someone stole a cash register. Some customers, learning about their system, have left in a huff.

Espresso at Slow Bloom Coffee Cooperative, a coffee shop in Redlands.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

The biggest issue, Bader admitted, is “coming to terms with how to handle scenarios of discipline in the workplace” — someone who didn’t do all their shift duties, for instance. “None of us feel super comfortable enforcing rules and policies.”

In other words, no one wants to act like a boss because everyone’s the boss. But those scenarios have been so few and far between that Slow Bloom has yet to lose a single founder and is looking forward to create a model where more co-owners can join.

“I think something is in the air,” Bader added. “Young people are seeing themselves working longer and longer in the same job category and not moving up. People are getting a sense of their place in the chain as their companies get bigger. And they hear the clock ticking and ask, ‘I either do something, or I get left behind.’”

I bade farewell to the three and walked back into Slow Bloom. It was busy when I first arrived, and it was now packed. I ordered a tamarind slush to go from Danny Storll.

Daawud Smith, of San Bernardino, reads at Slow Bloom Coffee Cooperative in Redlands. Smith was drawn in by the “positive vibes” of the coffee shop.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

“The best thing about this is you’re not punished for caring,” said the former Augie’s catering manager. “Bosses put more work on you, exploit you, just because you want to do better. Caring here grows the pot for everyone. It’s such a freeing thing to be a part of.”

A line was forming behind me. I moved out of the way, and a regular took my spot.

“Good morning!” Storll said. “Usuals?”

This story originally appeared on LA Times