Robbie Robertson, the driving force behind the pioneering rock ’n’ roll group the Band, died on Wednesday. He was 80.

His death was confirmed by his longtime manager, Jared Levine.

In a statement, Levine said that Robertson died in Los Angeles after a long illness. “Robbie was surrounded by his family at the time of his death, including his wife, Janet, his ex-wife, Dominique, her partner Nicholas, and his children Alexandra, Sebastian, Delphine, and Delphine’s partner Kenny,” the statement read. “He is also survived by his grandchildren Angelica, Donovan, Dominic, Gabriel and Seraphina. Robertson recently completed his fourteenth film music project with frequent collaborator Martin Scorsese, ‘Killers of the Flower Moon.’ In lieu of flowers, the family has asked that donations be made to the Six Nations of the Grand River to support a new Woodland Cultural Center.”

As the Band’s chief songwriter and grand conceptualist, Robertson turned old American folklore into modern myths, a knack that gave a timeless quality to such songs as “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”; it was as if he had unearthed the songs, not written them. Robertson specialized in portraits of bygone figures and institutions, writing odes to Confederate soldiers, blacksmiths, medicine shows and whistle stops, his tall tales given weight and energy by the heft of the Band.

“Music From Big Pink” and “The Band,” the group’s first two albums, arrived at the twilight of the 1960s, helping to shift rock away from the heady excesses of the psychedelic era and into something rugged and elemental, an evolution that had a seismic effect on the group’s peers.

“The Band has leapfrogged all its competitors,” The Times’ Robert Hilburn wrote in 1970, “and emerged as the chief challenger to the Beatles’ position of rock supremacy.”

The Band in 1971, from left: Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko and Garth Hudson.

(Gijsbert Hanekroot / Redferns / Getty Images)

Robertson rarely sang in the Band but he was unquestionably its leader, assuming control of the initially egalitarian outfit when his bandmates demonstrated they had no desire to take that position. He played that role with charismatic ease, a quality showcased in “The Last Waltz,” Martin Scorsese’s documentary about the Band’s 1976 farewell.

Flashing a wide smile and his knack for spinning yarns, Robertson acted as the ringleader in “The Last Waltz,” widely regarded as one of the greatest concert films ever made. By the time the film was released in 1978, Robertson had parted ways with the Band — they’d later reunite without him — and his bond with Scorsese deepened. Scorsese became Robertson’s lifelong collaborator, with the guitarist supervising music on the director’s films from “Raging Bull” in 1980 to “Killers of the Flower Moon” in 2022.

This regular cinematic work allowed Robertson to pursue an idiosyncratic career as a solo recording artist. After a decade’s absence from music, he returned in 1987 with a self-titled debut designed to sound at home alongside U2 and Peter Gabriel. Robertson gradually left the mainstream behind in the 1990s, as he explored his Native American musical roots and dabbled with electronica, yet he preserved the Band’s legacy by supervising deluxe reissues and a documentary, and by publishing his autobiography, “Testimony,” in 2016.

Robertson’s impact upon rock ’n’ roll was immense and immediate. George Harrison’s latter-day work with the Beatles bore signs of the Band’s influence and Eric Clapton wrote in his 2007 memoir, “It stopped me in my tracks. … Here was a band that was really doing it right, incorporating influences from country music, blues, jazz and rock, and writing great songs.” Decades later, the depth of the Band’s reach became clear, as the alt-country of the 1990s and the Americana of the 21st century all used its music as a blueprint.

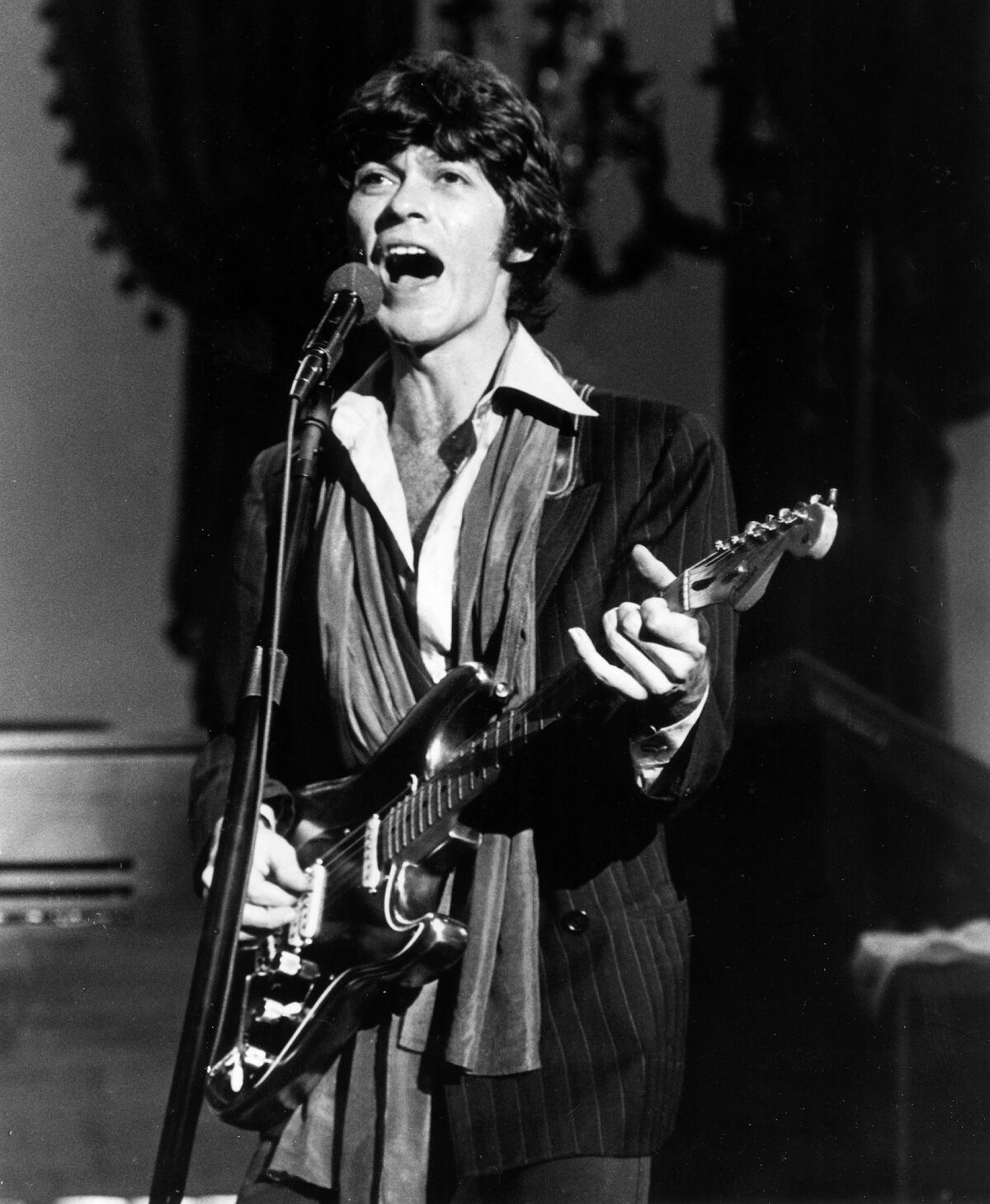

Robbie Robertson performing in the 1978 concert film “The Last Waltz.”

(Larry Hulst/Getty Images)

Born Jaime Royal Robertson on the Six Nations Reserve outside of Toronto, Ontario, on July 5, 1943,the future musician was the son of Rosemarie Dolly Chrysler, who claimed Mohawk and Cayuga as her heritage. Rosemarie was married to James Robertson, an army man whom Robbie believed to be his father. But when his parents separated when Robbie was in his early teens, his mother revealed that his biological father was Alexander David Klegerman, a professional gambler she met while James was stationed in Newfoundland.

Robertson was drawn to characters like Klegerman — hucksters who operated on the fringes of society — and he spent some time as a teenager working with traveling carnivals before he felt the pull of rock ’n’ roll. He’d been fascinated with music as a child, listening to American radio broadcasts of rock ’n’ roll and R&B while learning how to play guitar.

In his teens, Robertson started gigging with local bands, then formed his own group, first called Thumper and the Trambones, then Robbie and the Robots as a salute to a central character in the classic 1956 sci-fi film “Forbidden Planet.” Robertson’s next outfit, the Suedes, shared a bill with Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks, and the Arkansan rockabilly singer took a shine to Robertson, while the fledgling guitarist was infatuated with Levon Helm, the drummer of the Hawks.

Robertson worked his way into the inner circles of the Hawks, writing a pair of original tunes (“Hey Baba Lou” and “Someone Like You”) for Hawkins. Hawkins was so impressed that he sent Robertson to the Brill Building to choose the rest of the material for what became his 1959 LP, “Mr. Dynamo.” Robertson became the bassist in the Hawks shortly afterward. His adolescence at times could be a point of contention with club owners, who were reluctant to allow underage musicians in their venue; Hawkins had to sweet-talk the proprietors.

The teenage Robertson graduated to the lead guitar slot within a matter of months. “I was trying to do something with my playing that was like screaming at the sky,” he wrote in “Testimony,” developing a taut, penetrating style he’d sustain through the heyday of the Band. As the Hawks toured across North America, they acquired bassist Rick Danko, pianist Richard Manuel and multi-instrumentalist Garth Hudson, the lineup that would become known as the Band later in the 1960s.

The Hawks broke away from Ronnie Hawkins in 1964, soon adopting the name Levon and the Hawks. The group played a similar circuit to Hawkins, landing residencies on the Jersey shore, but they also worked their way into the blues scene of New York City, playing on John Hammond Jr.’s 1965 album, “So Many Roads.” During this time, Levon and the Hawks recorded three Robertson originals that were released over two 45s on Atco.

Late in the summer of 1965, Albert Grossman contacted Robertson with the intention of setting up a meeting between his client Bob Dylan and the Hawks. Originally, Dylan planned to hire Robertson as a guitarist, an offer Robertson rejected, but he did sit in on two Dylan concerts, bringing Helm along as the drummer. Encouraged by the shows, Dylan rehearsed with the band as they closed out a Toronto residency, then hired the band for his fall tour of 1965.

Dylan opened these shows with an acoustic set, then unleashed the loud, electrified Hawks on his unprepared audience. Crowds didn’t embrace the full-throated roar of the Hawks but they plowed ahead, only without Helm, who decided he didn’t want to play to hostile listeners. The rest of the Hawks soldiered on with a rotating series of drummers into 1966. That tour’s emotional climax arrived at Manchester Free Trade Hall on May 17, when somebody in the audience cried out “Judas!” in response to Dylan’s rock ’n’ roll, a moment that was immortalized on bootlegs and later officially released. Between the U.S. and U.K. tours, Dylan recorded the single “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” with the Band, then enlisted Robertson for part of the Nashville sessions for “Blonde on Blonde.”

Dylan’s wild years came to a sudden halt on July 29, 1966, when he suffered a neck injury in a motorcycle accident. As he headed to upstate New York to recover, the Hawks were kept on a retainer, with Dylan inviting the group to Woodstock in February 1967. Robertson headed upstate with his new girlfriend, Dominique Bourgeois; they’d marry that year and subsequently have three children together before divorcing in the mid-1970s. Danko, Manuel and Hudson followed in their footsteps, renting a house in West Saugerties, N.Y., they’d nickname “Big Pink.”

With a primitive recording studio installed in its basement, Big Pink became the creative center for Dylan and the Hawks. The five musicians would hunker down to play old folk, blues and country songs, then turn their attention to new tunes intended to be songwriting demos for Dylan. By the end of the summer, Helm returned to the fold and the group wound up with more than 130 recordings . These homemade, casual recordings were not designed for public consumption, yet interest was stoked when Jann Wenner published an editorial in Rolling Stone calling for their release, helping set the stage for 1969’s “The Great White Wonder,” an illicit collection of basement tape highlights commonly acknowledged as the first rock ’n’ roll bootleg.

Dylan gradually loosened his ties with the Band in early 1968 — they supported him at two Woody Guthrie memorial concerts at Carnegie Hall that January — while Albert Grossman, who was now their manager, secured a contract with Capitol Records. Working with producer John Simon, the group recorded “Music From Big Pink,” an album whose painterly, evocative production contained passing hints of the nervy energy of the Hawks. “Music From Big Pink” blended the intimacy of folk with the rollicking ramble of a juke joint, the mood shifting as often as the lead singers. Helm, Danko and Manuel traded leads, sometimes individual lines, over the course of the record, with Robertson singing just one tune: “To Kingdom Come,” one of his four originals on the 11-track album.

Indeed, the entire group had an air of mystery: Their name was intentionally generic; their photos were not visible on the outer artwork; the group didn’t tour or do interviews. Not long after the album’s release, Aretha Franklin and Jackie DeShannon each cut their own version of “The Weight,” the first step in the song becoming a modern-day standard.

The Band’s cultivated mystery started to lift with “The Band,” a sequel they swiftly cut at a pool house they leased from Sammy Davis Jr. Leaner and louder than their previous work, “The Band” ran the gamut from delicate, plaintive folk (“Whispering Pines”) to funky rock ’n’ roll (“Up on Cripple Creek”), with “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” — a Civil War tale told from the perspective of a Confederate soldier — anchoring the album. Like “The Weight,” “Old Dixie” was popularized through covers, with Joan Baez having a Top 10 hit with it in 1971. Unlike “Music From Big Pink,” “The Band” bore songwriting credits from Robertson on every track and no lead vocals from the guitarist at all (he’d not sing again on a Band album until their last, “Islands”).

“The Band” placed the Band squarely within the popular zeitgeist, earning enough attention to garner them a Time magazine cover in 1970. Robertson tentatively started to pursue projects outside of the group, producing the acclaimed eponymous 1970 debut by singer-songwriter Jesse Winchester, but the Band remained his primary focus. Cracks began to develop within the group starting with “Stage Fright,” a 1970 album recorded with pop wunderkind Todd Rundgren. Robertson enjoyed the experimental energy Rundgren brought to the sessions but the engineer clashed with other Band members, many of whom started a slow slide into substance abuse. With Helm, Danko and Manuel all experiencing some form of debilitating toxicity, Robertson rallied the group forward through “Cahoots,” a 1971 album that showed signs of fatigue; of its 11 songs, only “Life Is a Carnival” — a song Robertson co-wrote with Helm and Danko — became a part of the Band’s canon.

The Band, from left: Rick Danko, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson.

(Gijsbert Hanekroot/ Redferns / Getty Images)

Pulling back from the studio and the road, the Band bided their time for a while. Their New Year’s Eve stint at New York’s Academy of Music in 1971 became the 1972 double album “Rock of Ages.” The group stirred back to life in 1973, knocking out an amiable collection of rock ’n’ roll oldies called “Moondog Matinee” and headlining the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen alongside the Grateful Dead. At the end of the year, the Band reunited with Dylan to record “Planet Waves,” an album they supported with a blockbuster tour in 1974; the closing stint at Inglewood’s Forum was condensed into the double album “Before the Flood,” released in the summer of 1974. The following year, one last Bob Dylan & the Band project emerged when Robertson produced a double-LP set of “The Basement Tapes,” cleaning up the original 1967 recordings with some overdubs and adding a few Band outtakes to create the illusion they were equal partners to Dylan.

The Band reconnected with their past in another way: They sought to re-create the clubhouse atmosphere of Big Pink by renting a Malibu ranch called Shangri-La (previously the site where the talking-horse sitcom “Mr. Ed” was filmed) and converting it into a recording studio. Other musician friends spent time at Shangri-La — Eric Clapton cut his 1976 LP, “No Reason to Cry,” there, a record that featured all five members of the Band — while the Band recorded “Northern Lights — Southern Cross,” a 1975 release that was their strongest, most cohesive album since their second record. Once Robertson wrapped up his production duties on Neil Diamond’s “Beautiful Noise,” the Band launched a supporting tour for “Northern Lights — Southern Cross” in the summer of 1976.

Things quickly fell apart. Richard Manuel sustained a neck injury in a boating accident, forcing the Band to cancel a portion of the tour and prompting Robertson to consider an escape route. He conceived “The Last Waltz,” a lavish farewell to the stage to be delivered at the Winterland Ballroom on Thanksgiving Day 1976. Robertson decided to preserve the event, so he asked Scorsese, fresh off the release of “Taxi Driver,” to direct a documentary. The pair formed an instant and deep bond, evident in the finished film, which portrays Robertson as a movie star in waiting.

Van Morrison, from left, Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson performing “I Shall Be Released” from 1978’s “The Last Waltz.”

(United Artists / Getty Images)

Within the Band, there was discontent about whether the concert closed the curtain on their years as a touring act or on their career overall; Robertson claimed the former, Helm the latter. The drummer proved to be correct. Robertson spent much of 1977 working with Scorsese in postproduction on “The Last Waltz,” dreaming up ideas like shooting on-camera interviews with the group and filming the Band playing on a soundstage. “The Last Waltz” and its accompanying soundtrack appeared in 1978, helping stoke Robertson’s cinematic dreamsn. He secured a deal with MGM and developed a film based on his teenage experiences with a carnival. During preproduction, Robertson leapt from producer to star, appearing alongside Jodie Foster and Gary Busey in the 1980 film “Carny.”

Robertson didn’t prove to be a movie star but he found space in the film industry, working alongside Scorsese as a music advisor on “Raging Bull” and “The King of Comedy.” For the 1985 “The Hustler” sequel “The Color of Money,” Robertson co-wrote the theme song, “It’s in the Way That You Use It,” which Clapton recorded; it was the first time Robertson had a presence on rock radio in a decade.

Soon, Robertson launched his solo career, hiring Daniel Lanois to co-produce his self-titled debut. Robertson next released “Storyville,” a 1991 album inspired by the sounds and legends of New Orleans.

“Storyville” was the last conventional rock album Robertson would make for a while. “Music for the Native Americans” found him collaborating with the Red Road Ensemble, a group of Native Americans who helped him trace his heritage. Robertson moved further into the future with “Contact From the Underworld of Redboy,” an electronica fusion made in collaboration with Marius deVries and Howie B. After its release in 1998, Robertson slowed the pace of his solo projects, taking a full 13 years before returning in 2011 with “How to Become Clairvoyant,” a semiautobiographical record sporting cameos by Clapton, Steve Winwood, Tom Morello and Trent Reznor. His 2019 album, “Sinematic,” coincided with the appearance of Scorsese’s gangster epic “The Irishman”; the film’s quasi-theme song, “I Hear You Paint Houses,” was the centerpiece of the album.

Robertson was credited as executive music producer or music supervisor on every Scorsese feature from 2002’s “Gangs of New York” to 2022’s “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

He also did other movie work. He supervised the soundtrack to the John Travolta film “Phenomenon,” helping bring together Clapton and producer Babyface for the mellow soul of “Change the World,” which would take home Grammys for song of the year and record of the year in 1997. Robertson also worked on Oliver Stone’s NFL saga “Any Given Sunday.”

Robertson spent some time working as an A&R executive at DreamWorks Records in the early 2000s, helping the label sign Nelly Furtado. He also spent a considerable amount of time tending to thoughtful reissues of the Band’s catalog, shepherding the monumental 2005 box “The Band — A Musical History,” several anniversary editions of “The Last Waltz” and 50th-anniversary editions of their core catalog that offered fresh remixes. He also told his story through his 2016 memoir “Testimony” and the 2019 documentary “Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band.”

Robertson sold his music publishing, recorded interests and rights to his name, image and likeness for a reported $25 million to Iconoclast in 2022.

Following the Band’s induction into the Canadian Hall of Fame in 1989, the Band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994. Robertson received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Academy of Songwriters in 1997. In 2008, he received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. He was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2011.

This story originally appeared on LA Times