Teacher Christopher Gleditsch leads students in AP U.S. Government class at KIPP DC College Preparatory in Washington, D.C.

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

Teacher Christopher Gleditsch leads students in AP U.S. Government class at KIPP DC College Preparatory in Washington, D.C.

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

As high school seniors at KIPP DC College Preparatory in Washington, D.C. took their seats in AP U.S. Government class this week, they were already talking about the day’s lesson: what had just happened in the U.S. House of Representatives.

“Well, it happened last night,” said teacher Christopher Gleditsch. He was talking about what he had prepared students for in class a day earlier: the ouster of Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) as Speaker of the House.

He hit play on a video clip showing the vote and its momentous result.

“And with that gavel, history was made. This has never happened before in American history,” Gleditsch told the class.

The timing was good — the class had just covered the legislative branch and its leaders. The upheaval on Capitol Hill was a chance for the class to look at how well — or not — that structure is working right now.

Gleditsch asked why a small group of fellow Republicans went after McCarthy.

“They decided to remove him because he was siding with the Democrats at certain times. … He wasn’t sticking to being a Republican,” answered a student named Sean. (NPR is not using students’ last names because they are minors).

A few of the students in the AP U.S. Government class at KIPP DC College Prep.

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

A few of the students in the AP U.S. Government class at KIPP DC College Prep.

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

“But like … isn’t that how Congress is supposed to work? Aren’t you supposed to work together?” Gleditsch countered.

“I feel like that’s how it’s supposed to be,” a student named Jakiya suggested. “But how Congress is set up now, it’s like Republicans and Democrats will always have that separation going on because there’s certain situations that they cannot agree on and they don’t agree on. Like when we learned about Republican philosophies and Democrat philosophies, they see things in two different ways.”

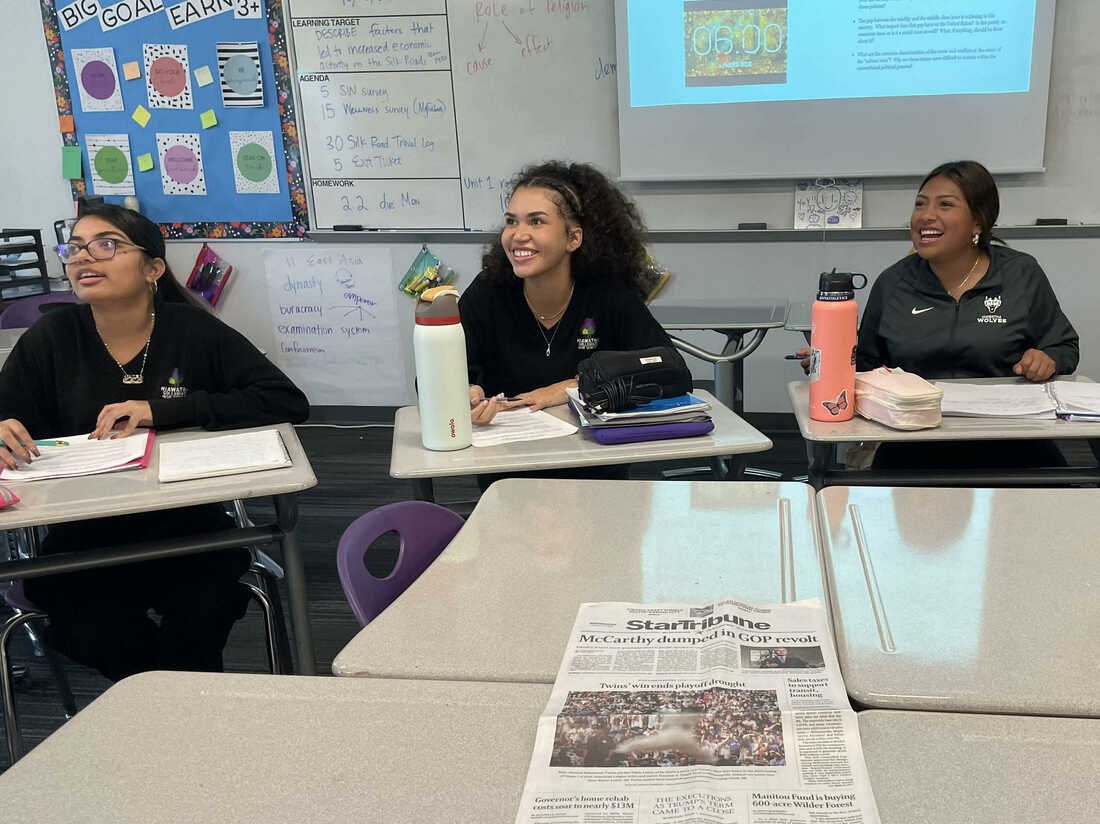

Halfway across the country, polarization was also top of mind in Joe Kennealy’s class at Hiawatha Collegiate High School in Minneapolis. His students sat in a circle, with the day’s Star Tribune newspaper strewn out in the center with the top headline “McCarthy Dumped in GOP Revolt.”

“All right, seniors, I will turn off my voice and hand it over to you guys,” Kennealy said as the students settled in for the discussion section of class.

A senior named Luke said it can be good to disagree: “But I think that if those disagreements become demonizing each other, just because you have those different values, you’re never actually going to get common ground.”

His classmate Sarah countered, saying the consequences can become too high to not fight for your beliefs.

“If we talk about the Supreme Court decision about overturning Roe v. Wade, it feels like sometimes there needs to be polarization because sometimes the things that are happening in the government is, like, a direct attack on someone’s identity,” she said. “If you feel like your identity is being attacked, then you’re obviously going to have more passion.”

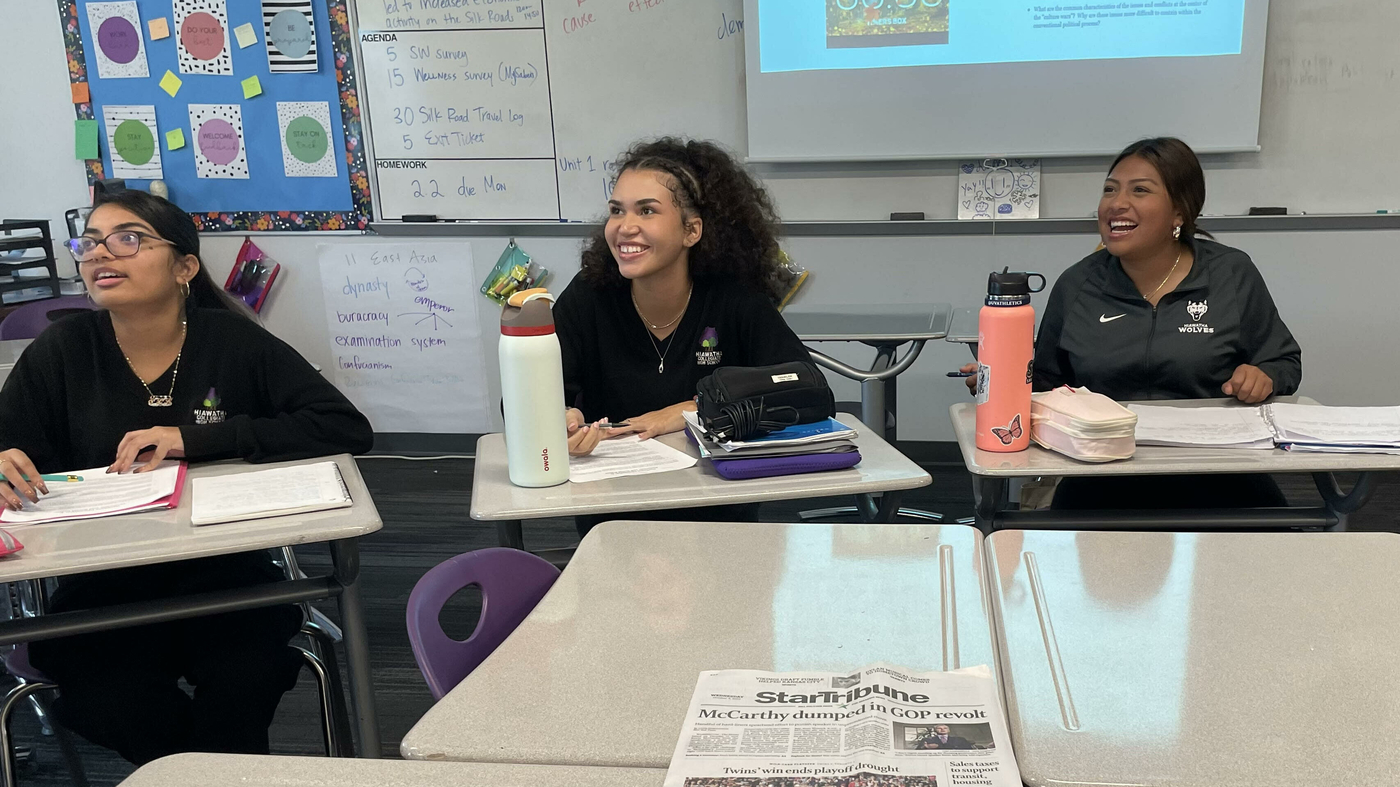

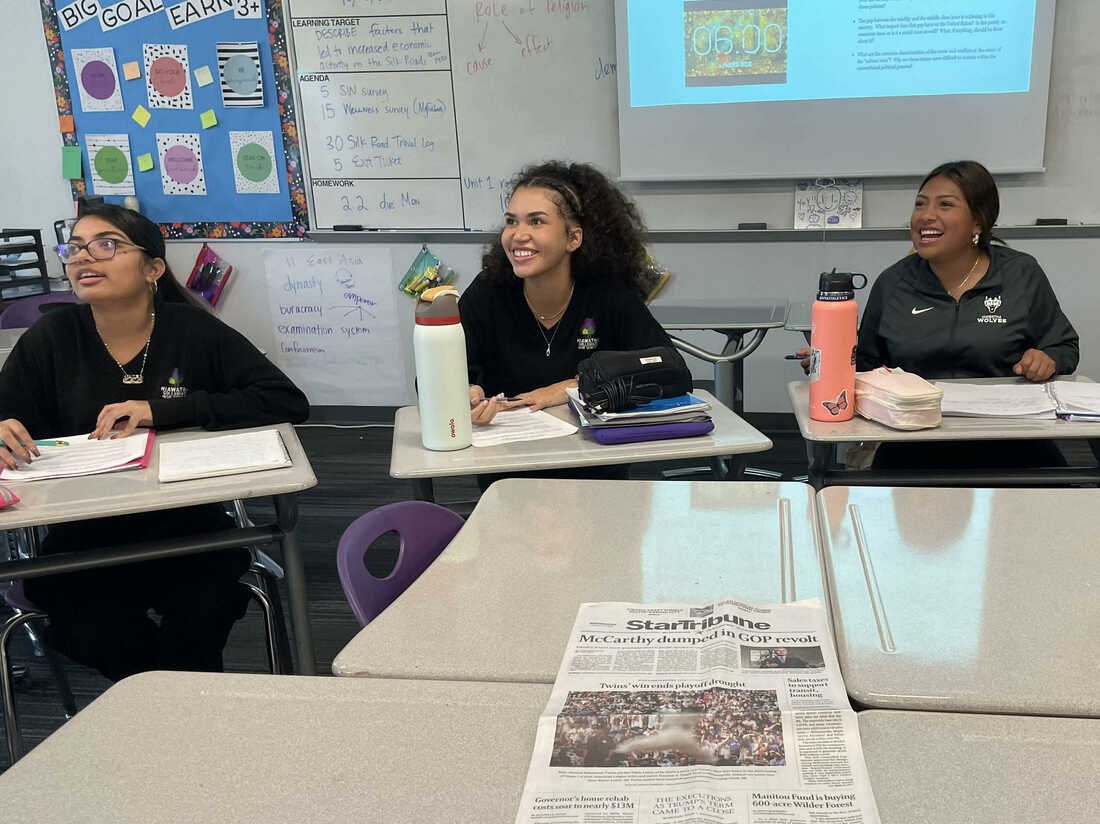

Students at Minneapolis’ Hiawatha Collegiate High School discuss polarization within the federal government.

Meg Anderson/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meg Anderson/NPR

Students at Minneapolis’ Hiawatha Collegiate High School discuss polarization within the federal government.

Meg Anderson/NPR

These conversations about government aren’t really a priority in a lot of schools across the country. That’s according to Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University.

“One of the things about civic education that’s challenging is that we neglected it for the past three decades or so for sure,” she says.

A 2021 report funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the U.S. Department of Education estimated that the federal government spends about $50 per student per year on studies related to science and math, but only five cents on civics.

That’s a problem, Kawashima-Ginsberg says, because not only does civics education teach students how the government is supposed to function, it also teaches students how to disagree with one another in a productive way.

“Schools can offer different opportunities in that students will meet somebody that thinks differently than themselves. And that practice of doing that with somebody and then still coming back with something they learned is going to go a long way,” says Kawashima-Ginsberg, who was on the report committee.

The stakes are high, says Paul Carrese, director of the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership at Arizona State University, who was also on the committee.

“We are clearly showing signs that we are in a dangerous domestic political environment with anger and demonization at one extreme, disaffection, people just tuning out at another extreme,” he says.

But, he says, teachers can actually harness that as a teachable moment — exactly like what the teachers in D.C. and Minneapolis did.

“One idea is, for teachers at any level, to make lemonade out of the lemon, when there is bad news or something striking in the news,” he says. “It’s a great human story, the United States of America. I’m not saying we’re flawless or perfect, but it is a great human story. We ought to get young people excited about it.”

The turmoil on Capitol Hill provided fodder for high school civics classes, including one at KIPP DC College Prep in Northeast Washington, D.C.

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

The turmoil on Capitol Hill provided fodder for high school civics classes, including one at KIPP DC College Prep in Northeast Washington, D.C.

Laurel Wamsley/NPR

Back in the Minneapolis classroom, one student, Zakariya, was feeling less than enthused about the turmoil in the halls of Congress. But, he said, he’s not sure whether lawmakers care what he thinks.

“If I had an opinion, like, it wouldn’t really matter to them,” Zakariya says. “They’re all like closed door meetings, like all the rules that they make.”

Kennealy, his teacher, was across the room listening.

“I’d like to think that that’s not where [Zakariya]’s going to end his journey,” Kennealy says. “But I do think civics and government class, if it’s done right, does help students to understand more of those systems that are in place that they’re already in.”

The classes give them tools to make sense of what’s happening on Capitol Hill – and to recognize whether Congress is functioning like it should.

This story originally appeared on NPR