California is set to adopt regulations that will allow for sewage to be extensively treated, transformed into pure drinking water and delivered directly to people’s taps.

The regulations are expected to be approved Tuesday by the State Water Resources Control Board, enabling water suppliers to begin building advanced treatment plants that will turn wastewater into a source of clean drinking water.

The new rules represent a major milestone in California’s efforts to stretch supplies by recycling more of the water that flows down drains.

“We’re creating a new source of supply that we were previously discharging or thinking of as waste,” said Heather Cooley, director of research at the Pacific Institute, a water think tank in Oakland. “As we look to make our communities more resilient to drought, to climate change, this is really going to be an important part of that solution.”

Water agencies in many areas of California have been treating and reusing wastewater for decades, often piping effluent for outdoor irrigation or to facilities where treated water soaks into the ground to replenish aquifers.

The regulations will enable what’s known as “direct potable reuse,” putting highly treated water straight into the drinking-water system or mixing it with other supplies.

Cooley and other water experts say it’s inaccurate to call this “toilet to tap,” a term that was popularized in the 1990s by opponents of plans to use recycled water for replenishing groundwater in the San Gabriel Valley. They say the sewage undergoes an extremely sophisticated treatment process, and scientific research has shown that the highly purified water is safe to drink.

“This is really about recovering resources, not wasting precious resources,” Cooley said. “This is really, I think, an exciting opportunity for helping to realize that vision of a more circular sort of approach for water.”

The process of developing the regulations, which was required under legislation, has taken state regulators more than a decade. It included a review by a panel of experts.

Rupam Soni, a community relations team manager, shows a cutaway of part of a reverse-osmosis treatment system during a tour of the Metropolitan Water District’s pilot water recycling facility in Carson.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

“We wanted to absolutely make sure that we put public health first priority, so that the public had confidence,” said Darrin Polhemus, deputy director of the State Water Board’s Division of Drinking Water.

“We have a very thorough set of regulations,” Polhemus said. “It has broad support, and we think we’ve gotten it to a point where everybody is comfortable with what it presents.”

Building plants to purify wastewater is expensive, and it’s likely to be years before any Californians are drinking the treated water. But Los Angeles, San Diego and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California are all planning to pursue direct potable reuse as part of ongoing investments in recycling more wastewater.

The regulations detail requirements for infrastructure, treatment technologies and monitoring, Polhemus said, and ensure “triple redundancy for each of the areas we’re treating for,” including bacteria and viruses, as well as chemicals.

The water will go through various stages of treatment, passing through activated carbon filters and reverse-osmosis membranes, as well as undergoing disinfection with UV light, among other treatments.

The regulations require such thorough purification that at the end of the process, minerals will need to be added back to achieve a taste and chemistry resembling typical drinking water.

“This will be by far the most well-treated, highest-quality water served to the public,” Polhemus said. “It’s an incredible amount of treatment.”

Once the regulations are approved by the State Water Board, they need to be approved by the Office of Administrative Law; this is expected to happen next year.

The treatment technology is similar to the process used for desalinating seawater, but recycling wastewater requires less energy and is less costly than turning saltwater into freshwater. Polhemus said the costs for purifying wastewater will probably be about half those of desalinating ocean water.

Direct potable reuse has for years been a strategy in other water-scarce parts of the world, including Namibia and Singapore. Some communities in Texas are also doing it. Colorado has rules in place allowing potable reuse, while Arizona and Florida are developing regulations.

In California, some agencies have for years been conducting indirect potable reuse, in which highly treated water is used to replenish groundwater and is later pumped out, treated and delivered as drinking water.

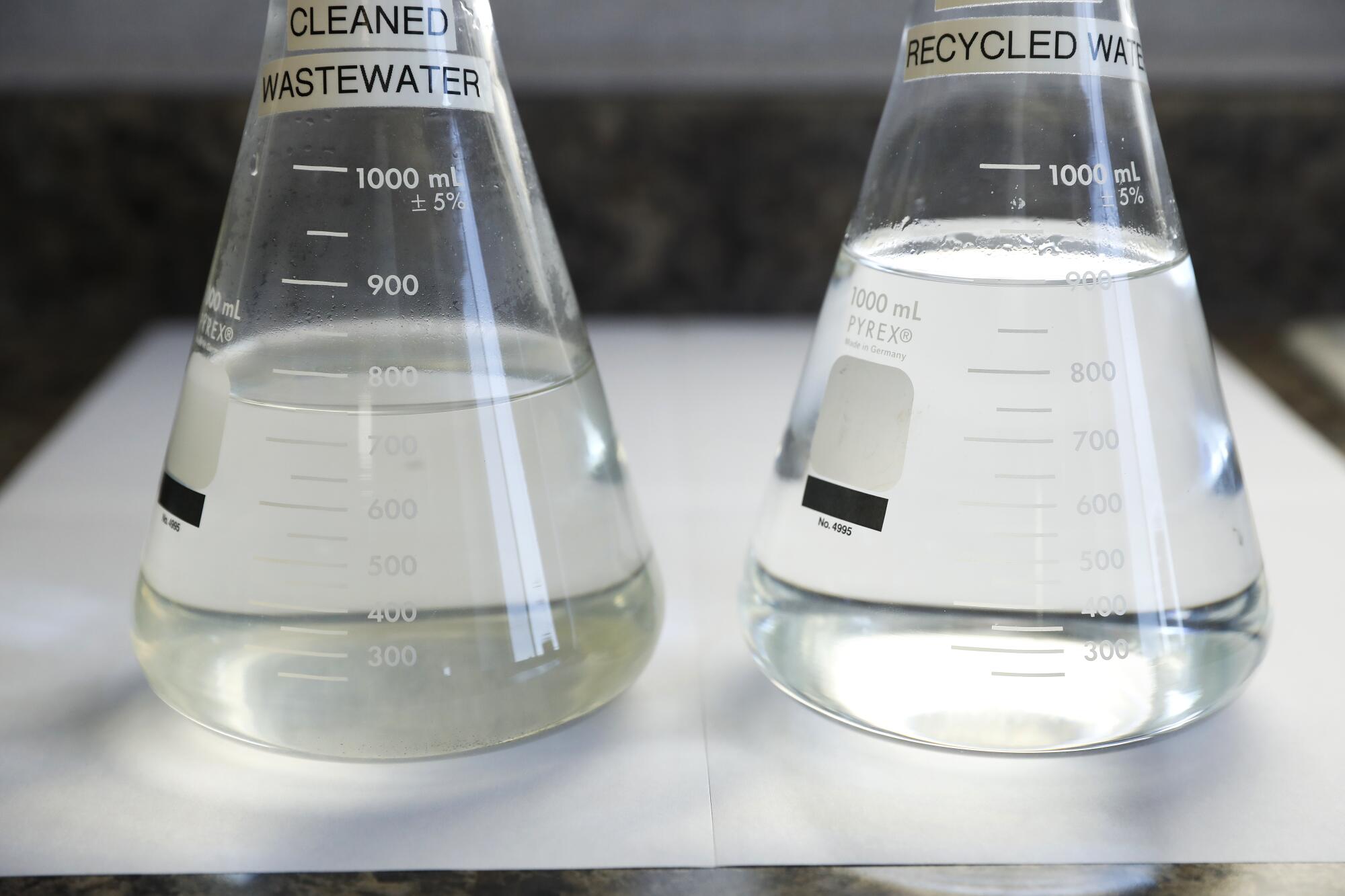

A cleaned wastewater sample, left, and a purified recycled water sample, right, are displayed at the Metropolitan Water District’s pilot water recycling facility in Carson.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Orange County, for example, has its Groundwater Replenishment System, the world’s largest project of its kind . The system purifies wastewater using a three-step advanced treatment process, and the water then percolates and is injected into the groundwater basin, where it becomes part of the supply.

While Orange County plans to stick with indirect potable reuse, Polhemus said, other water districts are looking at direct reuse as an approach that saves costs by using existing infrastructure rather than building separate systems for recycled water.

This strategy also offers cities and agencies a new route for reducing reliance on imported supplies and scaling up the use of recycled water — a source that managers view as relatively drought-proof.

“Our communities are always going to generate wastewater, even in the worst drought. And having this available can really augment that supply and add resiliency,” Polhemus said.

Recycling more wastewater brings other environmental benefits, reducing the amount of treated effluent that flows into coastal waters.

“It’s easier on the environment you’re taking the water from, it’s easier on the environment you’re discharging it to and sets us up to be better stewards of our environment overall,” Polhemus said.

The complexity and costs of the treatment plants mean that large, well-funded agencies will adopt the technology first, Polhemus said. Direct potable reuse also is suited to coastal areas, he said, because the reverse-osmosis treatment, like a desalination plant, generates brine that can be discharged offshore.

As for how much purified water might be used, if some coastal communities are able to get 10%-15% of their supply from treated wastewater during a drought, that would represent a significant improvement in diversifying supplies, Polhemus said.

“Someday, it could be 25% to 40% of some communities’ water supply,” Polhemus said. “At some point, we could recycle the majority of wastewater that now flows to the ocean just as treated wastewater.”

The Metropolitan Water District plans to start direct potable reuse as part of its Pure Water Southern California project, building a $6-billion facility in Carson that is slated to become the country’s largest water-recycling project.

It’s scheduled to deliver its first treated water as soon as 2028. Initially, the district says, the supplies will be used largely to replenish groundwater basins for later use, with some also going to serve oil refineries and other industrial users.

By 2032, MWD officials plan to be producing 115 million gallons of purified water a day. Of that, they expect to send 25 million gallons per day to a plant in La Verne to be mixed with other supplies from the Colorado River and Northern California, and delivered as drinking water throughout the region — an amount that’s projected to increase to 60 million gallons a day once the facility is operating at its full capacity of 150 million gallons .

Depending on how wet or dry a year is, the district will be able to store more water in aquifers or send more purified water directly into the distribution system, said Deven Upadhyay, the MWD’s executive officer and assistant general manager.

“We’re building that flexibility into the design of this program,” Upadhyay said. “If you needed to push more into direct potable reuse, you would be able to do that and back off of your deliveries to the groundwater basins.”

He said that flexibility is valuable as California deals with more extreme droughts fueled by climate change.

“Our view is that over time, those imported supplies will decline. And we want to take the water that is used, and reuse it as much as possible, and try to close that cycle of water use,” Upadhyay said. “Because it’s such a drought-proof supply, it really creates another degree of resilience for us.”

The Metropolitan Water District has a pilot water recycling project in Carson, where it plans to build the country’s largest recycling facility.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

The Metropolitan Water District functions as Southern California’s wholesaler, delivering supplies to cities and agencies that serve 19 million people in six counties.

About 450,000 acre-feet of wastewater is now recycled in Metropolitan’s service area, an amount equivalent to the water use of about 1.3 million households.

The MWD’s recycling project, as well as Los Angeles’ Operation Next and San Diego’s Pure Water , will dramatically increase the use of recycled water once they are built out, Upadhyay said.

“We should expect a doubling of recycled water that Southern California is producing and drinking by the time those three projects are completed,” Upadhyay said.

And part of that will come thanks to the state’s new regulations that enable direct reuse, he said.

“It’s a major milestone for the state,” Upadhyay said. “This is going to lead to water agencies throughout the state starting to plan for potable reuse projects in a way that results in a more resilient California water future.”

In the Bay Area, the Santa Clara Valley Water District also plans to pursue potable reuse.

In a study last year, researchers at the Pacific Institute said California recycles about 23% of its municipal wastewater and has the potential to more than triple the amount that is recycled and reused.

Cooley said some portion of that will come through direct reuse where it pencils out for communities.

“It’s just part of the puzzle in terms of helping us to realize the full potential for recycled water,” Cooley said. “This is an important piece of helping make our communities more resilient.”

There has been growing public acceptance of recycling water as people have experienced more severe droughts and seen recycling projects expand, Cooley said.

Still, she said, acceptance isn’t universal, and “it’s important to really address openly concerns that people have as communities consider this as an option.”

She said reusing more water is one strategy that California should adopt, along with capturing more stormwater and improving efficiency.

Peter Gleick, the Pacific Institute’s co-founder and president emeritus, pointed out that the water-recycling technologies in use today are fundamentally the same approaches used by astronauts on the International Space Station.

“It’s not toilet to tap,” Gleick said, adding that it’s better described as “toilet to an unbelievably sophisticated system that produces incredibly pure water to tap.”

In his book “The Three Ages of Water,” Gleick wrote that reusing water provides a valuable new supply and should be part of a set of solutions for long-term sustainability.

“High-quality water produced from wastewater is an asset,” Gleick wrote. “We have the ability and technology to produce incredibly clean water from any quality of wastewater, and we should rapidly expand the capacity to do so.”

Newsletter

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

This story originally appeared on LA Times