The named defendant in the federal lawsuit was California Secretary of State Shirley Weber, but there was never a doubt that the target was Donald J. Trump.

For a time, as the legal maneuvering proceeded through the fall, it appeared that Los Angeles could be treated to another of its celebrated courtroom dramas, this one a constitutional showdown pitting a colorful civil rights attorney against a volcanic former president in the courtroom of a judge known for his fiery judicial flair.

The case sought an order prohibiting Weber from placing the Republican presidential front-runner on the California ballot, based on the 14th Amendment’s insurrection clause.

It was also intended to be a trap. If Trump’s legal team took the bait and joined the case, then the former president could be forced to face a grilling under oath on his role in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol.

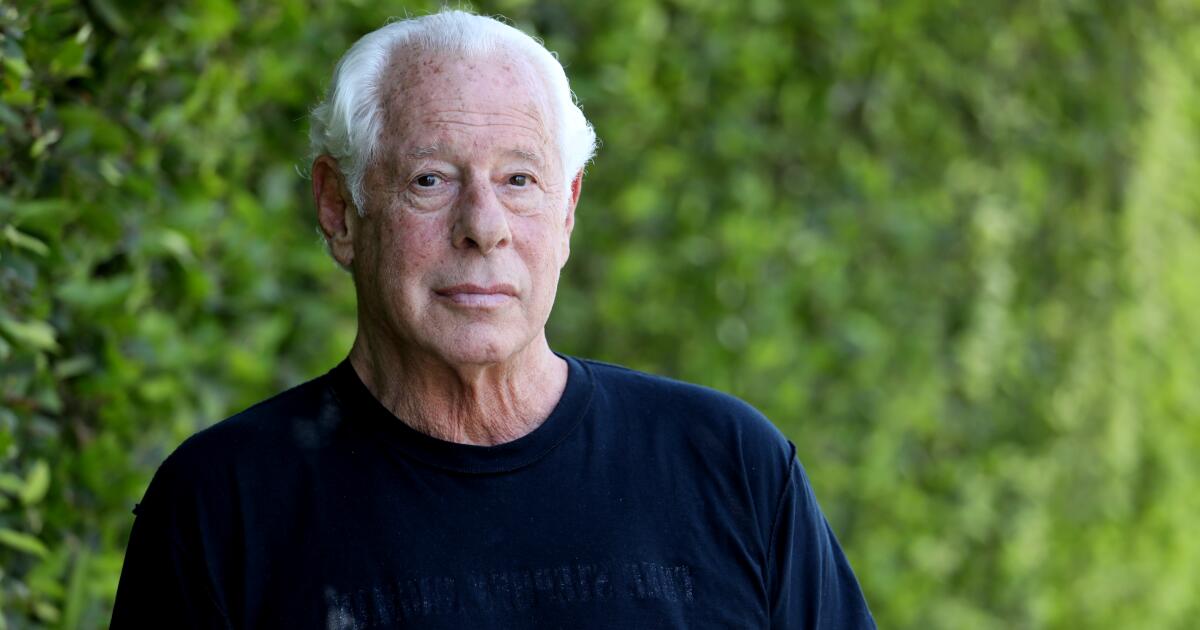

At least that was the theory of Stephen Yagman, an attorney both admired and reviled in local lore for his history of toppling sacred cows.

Over a span of two decades, Yagman broke legal ground in cases against the LAPD and the U.S. government, establishing that Los Angeles Police Department officers and their leaders can be held personally liable for civil rights violations and that prisoners at the Guantanamo Bay detention center had a right to due process. Then he suffered an ignominious fall with a 2007 federal conviction for tax evasion and bankruptcy fraud. In his 70s, more than a decade after serving 29 months in prison, Yagman regained his law license and resumed fighting for indigent victims of government abuse.

U.S. District Judge David O. Carter, a no less colorful figure than Yagman, has built a reputation for judicial unorothodoxy bordering on heavy-handedness. He’s held court on Skid Row and summoned mayors and supervisors to answer for their ineffective responses to homelessness. In two cases that were active at the time, Carter was holding L.A. County officials’ feet to the fire to extract a commitment for thousands of mental health beds and rebuffing efforts of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to wiggle out of a lawsuit over veterans housing.

More to the point of Yagman’s case, Carter had found in a 2022 ruling that stripped Trump legal adviser John Eastman’s attorney-client privilege that the two had “more likely than not” attempted to illegally obstruct Congress, calling it “a coup in search of a legal theory.”

Would Carter, who drew Yagman’s case because it was related to the earlier one, follow through with that reasoning? Yagman hoped so.

When Trump’s lawyers took the bait and petitioned Carter to intervene, Yagman virtually frothed with anticipation.

“This court, right here and now, has a unique opportunity to prevent a truly deranged and dangerous fool, Donald Trump, who perpetrated an assault on American Democracy, from again being president of the United States,” he wrote in a motion, noting that Trump “improvidently (for him) has intervened to make himself a party-defendant to the instant action.”

He buttressed his ever eccentric legalese with a flight of literary allusion invoking both Socrates and The Rolling Stones.

“Trump is a vile man. He has no virtue whatsoever,” Yagman wrote, appending a long footnote on the Greek philosopher’s concept of civic virtue.

“And contrary to what the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger sings … Trump, as today’s embodiment of the devil … deserves no sympathy….”

But it was to no avail. Not once, but twice in the months that followed, Trump’s lawyers raised legal technicalities to knock down Yagman’s flaming rhetoric.

The first was based on standing, a slippery legal concept meaning something akin to skin in the game.

Yagman’s case made the tortuous argument that his client, a Republican voter who planned to vote for Trump, would be disenfranchised if, after the March California primary, Trump was ruled ineligible to be president.

Carter dismissed the case in November, finding his client did not have standing because “the harm he alleges is too generalized.”

Yagman had a backup strategy, an amended complaint changing his case to a class action representing all Republican voters and naming Trump himself as a defendant on a novel theory of negligent infliction of emotional distress.

His clients, he argued, were “direct victims of Trump’s acts in creating and participating in insurrection,” both on Jan. 6 and in the “innumerable viewings of those acts on television, on the radio and in numerous publications….”

Reconsidering, Carter set a hearing for Jan. 8. But, over the holidays, Trump’s lawyers convinced the judge that a hearing was not necessary. In a Dec. 22 filing, Shawn E. Cowles of the Dhillon Law Group gave eight reasons why the case had no merit, ranging from presidential immunity and 1st Amendment protection to “reasons to doubt the veracity of Plaintiff’s claim that he is a registered Republican voter in Los Angeles County.”

The argument that carried the day for the former president was based on the statute of limitations. Ignoring Yagman’s contention that the injury was repeated every time Jan. 6 imagery appeared on TV, radio or in print, Carter ruled the case “time-barred” based on California’s two-year statute for negligent infliction of emotional distress.

Yagman, whose past victories included establishing that lawyers cannot be sanctioned for making disparaging comments about their judges, showed uncharacteristic magnanimity in defeat.

Carter, he said, is a good judge and decent human being.

“I’m happy enough with it because it’s him,” he told The Times. “Part of me is really sorry to see it go, I really wanted to depose Trump. But I’m ashamed of that because it would just be me playing games. I wouldn’t get anything out of that except chuckles.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this story.

This story originally appeared on LA Times