The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has signed off on a California oil company’s plans to permanently store carbon emissions deep underground to combat global warming — the first proposal of its kind to be tentatively approved in the state.

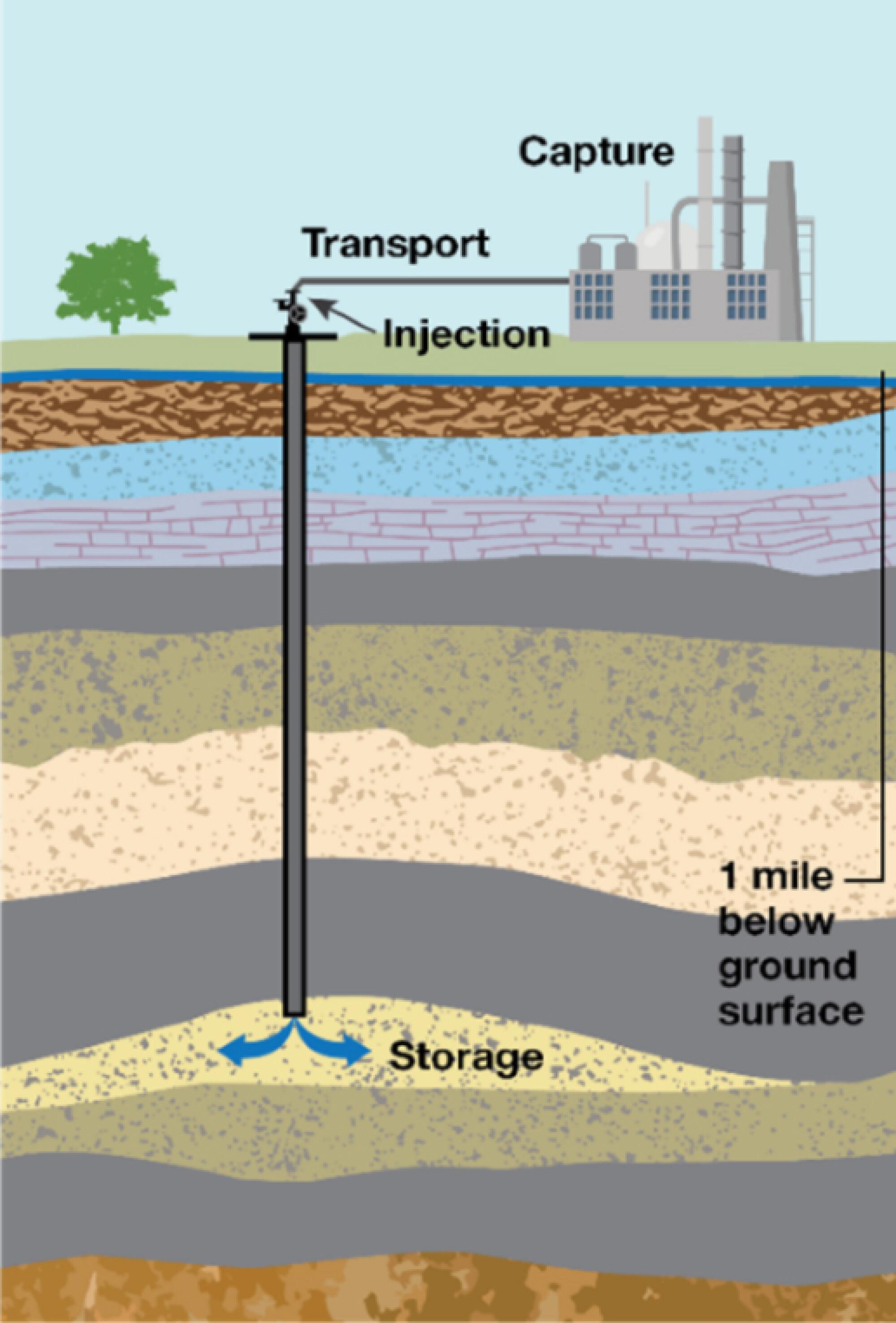

California Resources Corp., the state’s largest oil and gas company, applied for permission to send 1.46 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year into the Elk Hills oil field, a depleted oil reservoir about 25 miles outside of downtown Bakersfield. The emissions would be collected from several industrial sources nearby, compressed into a liquid-like state and injected into porous rock more than one mile underground.

Although this technique has never been performed on a large scale in California, the state’s climate plan calls for these operations to be widely deployed across the Central Valley to reduce carbon emissions from industrial facilities. The EPA issued a draft permit for the California Resources Corp. project, which is poised to be finalized in March following public comments.

As California transitions away from oil production, a new business model for fossil fuel companies has emerged: carbon management. Oil companies have heavily invested in transforming their vast network of exhausted oil reservoirs into a long-term storage sites for planet-warming gases, including California Resources Corp., the largest nongovernmental owner of mineral rights in California.

“CRC has been developing and operating subsurface reservoirs for decades in the state,” said Chris Gould, the company’s chief sustainability officer. “We have a deep and intimate knowledge of the subsurface characteristics.”

“It’s kind of reversing the role, if you will,” Gould added. “Instead of taking oil and gas out, we’re putting carbon in.”

In California, there are about a dozen applications — all sited in the Central Valley — that seek to collectively squirrel away millions of tons of carbon emissions in old oil and gas fields in exchange for government tax credits. But Greater Los Angeles is also “being evaluated” as a potential storage site, according to California Resources Corp. spokesperson Richard Venn.

The new carbon sequestration sector could mark a drastic transformation for fossil fuel companies and the communities that have built their economies around them.

Carbon sequestration projects capture CO2 from industrial sources and store them deep underground. In California, depleted oil reservoirs are expected to be used to store the planet-warming gas.

(U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

The transition has been met with a mix of cautious optimism and extreme skepticism. But public leaders are scrambling to consider what this will mean for the future of their communities, including Kern County, where planning officials have published renderings and economic prospects for a hypothetical carbon management business park.

“I know that there are people who are concerned that this is just a way for the oil companies to stay alive. And my answer is, yes, that’s actually true,” said Lorelei Oviatt, Kern County director of planning and natural resources. “At the end of the day, you want them to reinvent themselves, and no one seems to have any other good ideas on how we are supposed to keep our libraries open.”

Others are more reluctant to welcome such a new industry.

“I worry about the Central Valley becoming the repository of everything bad,” said Dean Florez, a member of the California Air Resources Board and native of Kern County. “Where did every prison go in the ‘80s? The valley. Where does all of L.A.’s [sewer] sludge go? The valley.”

California Resources Corp. has applied for permits for five carbon storage projects across the region — the most of any other company in the nation. It has partnered with Canadian-based Brookfield Corp., which has initially invested $500 million for the joint venture.

For every metric ton of carbon it captures and stores, the company stands to earn $85 in federal tax credits and possibly more if it qualifies for California state subsidies. The company also intends to encourage other industrial businesses to store their carbon emissions in their underground reservoirs in exchange for a fee.

The company said it plans to store emissions from its gas field operations, as well as a proposed hydrogen plant and direct air capture facility. Direct capture facilities use fans and filters to gather carbon dioxide straight from the atmosphere.

These operations, California Resources Corp. officials say, are in alignment with California’s climate plan, which calls for carbon emissions to be captured from state oil refineries, cement plants and other industrial facilities that require high levels of heat that can’t be achieved with renewable energy.

But environmental groups and some valley residents have serious concerns about this strategy. Some argue it prolongs heavily polluting industries rather than encouraging these businesses to switch to zero-emission technology.

Although carbon capture equipment collects CO2, other emissions like smog-forming nitrogen oxides or particulate matter would still be released. The San Joaquin Valley is already the most polluted air basin in the nation.

Florez, the state air board member, compared the technology to a catalytic converter, saying it addresses only greenhouse gas emissions, not the lung-damaging pollutants.

Florez said California officials need to clearly identify if carbon capture will serve as a bridge to zero-emission technology or whether it just perpetuates the use of fossil fuels.

Environmentalists also say that the transportation and injection of CO2 — an asphyxiating gas that displaces oxygen — could lead to dangerous leaks. Nationwide, there have been at least 25 carbon dioxide pipeline leaks between 2002 and 2021, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Perhaps the most notable incident occurred in Satartia, Miss., in 2020 when a CO2 pipeline ruptured following heavy rains. The leak led to the hospitalization of 45 people and the evacuation of 200 residents.

“Carbon capture and storage simply cannot function as a sustainable climate solution as it is a prohibitively expensive process that requires significant untested and unproven infrastructure,” said Chirag Bhakta, California director of advocacy nonprofit Food & Water Watch. “Further, the transportation and storage of captured carbon can lead to leaks, accidents and explosions that can release toxic substances into the surrounding environment. This can result in severe health risks, particularly to communities already living on the frontline of the climate crisis.”

State Sen. Henry Stern (D-Calabasas), a non-voting member of the state Air Resources Board, said the risks associated with carbon capture bring to mind the disastrous situation that occurred at the Aliso Canyon natural gas storage facility in the San Fernando Valley.

SoCalGas injects and stores methane inside a depleted oil reservoir in the Santa Susana Mountains near Los Angeles’ Porter Ranch neighborhood. But in October 2015, one of Aliso Canyon’s 115 gas wells developed an uncontrolled leak that lasted for nearly four months. About 100,000 tons of methane were released and more than 5,000 households were evacuated.

“On a gut, emotional level, as a resident, anything getting injected underground, especially by a fossil fuel company, I’m inherently skeptical,” Stern said.

However, Stern also acknowledged that storing CO2 underground is outlined in global, national and state climate plans — and the planet is running out of time to slow global warming.

“I worry if we debate forever, we’re going to be sitting here in another 10 years having the same conversation about some future model, and the world would be burning,” he said.

Under the EPA draft permit, California Resources Corp. must take a number of steps to mitigate these risks. The company must plug 157 wells to ensure the CO2 remains underground, monitor the injection site for leaks and obtain a $33-million insurance policy.

In addition, California Resources Corp. needs approval from the Kern County Board of Supervisors. Kern County has already prohibited carbon storage reservoirs from underlying residential or commercial areas, and officials intend to keep pipelines away from homes and sensitive habitat, according to Oviatt, the Kern County planning director.

“We are not interested in CO2 pipelines going through residential areas,” she said. “I don’t care how far back they are from the houses. They’re not things that I’m going to recommend.”

From an economic standpoint, the injection of CO2, by itself, is not expected to produce a significant number of new jobs. New hiring would come only from new incoming industries that would be attracted to the area near an injection site.

Kern County officials have also wrestled with how the phasing out of fossil fuels will affect their tax revenue. They have imposed an annual $250,000 charge for public safety and a $200-$400 yearly charge for each acre of land that sits above the injection area — an attempt to claw back some of what it plans to lose in oil revenue.

“If you pump oil out of it, then we tax it as an oil reservoir and we’re making money, right? But if you’re an oil company and you’re now going to use your land for something else, OK. That’s your right. My question is, is when you dial 911 for the CO2 leak, where’s the money come for the fire department to show up?”

But California Resources Corp.’s plan has come a long way from its inception more than two decades ago.

At least two earlier versions of the proposal planned to capture CO2 and inject it inside aging oil wells to flush out more petroleum. In 2022, however, the state Legislature passed a bill banning carbon capture projects from boosting oil production.

For Stern, the revisions to the project have made him more open-minded about the plan.

“If you clear all those hurdles, as well as new guardrails in place, it’s an amazing example of persistence,” Stern said. “Is this what it looks like to watch the evolution of the industry real-time? Who knows, after two decades, maybe this is the time.”

Newsletter

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

This story originally appeared on LA Times