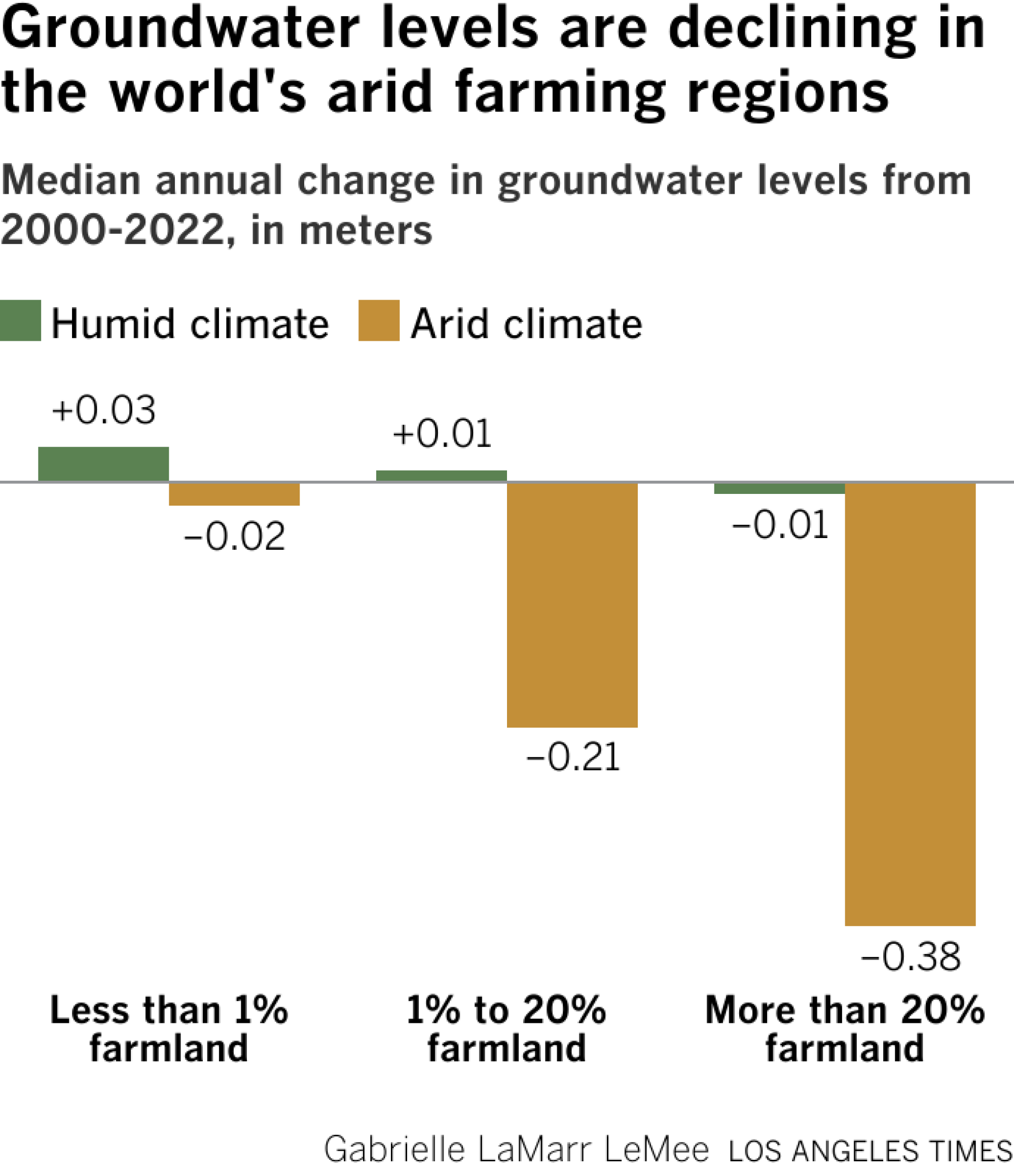

From California’s Central Valley to the croplands of Iran, groundwater depletion has accelerated over the last four decades across the world’s arid food-producing regions.

In many parts of the western United States, India, Chile, Spain, Mexico and other countries, groundwater levels have been rapidly declining as water is heavily pumped to irrigate farmlands, according to a new study analyzing measurements from 170,000 wells in more than 40 countries.

The research, published this week in the journal Nature, reveals that overpumping is taking a widespread and worsening toll on aquifers that hold critical reserves as many regions face more intense bouts of dry conditions with climate change.

The analysis shows that parts of California have some of the fastest declining aquifer levels in the world.

“Over and over again, we see places where groundwater is being depleted,” said Debra Perrone, an associate professor of environmental studies at UC Santa Barbara and one of the study’s lead authors. “Where we’re really seeing these trends is where we have arid climates.”

Many dry regions depend more on groundwater than areas with wetter climates. And where water levels are dropping because of overpumping, the consequences can include dry wells, diminished streams and sinking ground, as well as the loss of precious water reserves that accumulated underground over centuries or thousands of years.

While the study presents a stark picture of ongoing and pervasive groundwater depletion globally, the researchers also found that efforts to address the problem in some areas are successfully curbing declines and boosting aquifer levels.

“Our work demonstrates that rapid and accelerating groundwater declines are widespread but not inevitable,” said Scott Jasechko, a co-author and UCSB associate professor of water resources. “Declines can be slowed, stopped and even reversed, but much work needs to be done to address groundwater depletion.”

An irrigation system waters carrot fields in California’s Cuyama Valley in October.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

The scientists analyzed water-level measurements from monitoring wells in areas with available data. Examining 1,693 aquifers worldwide, they found that 36% of the aquifers declined significantly from 2000 to 2022 — at a median rate of at least 4 inches per year — while 6% of aquifers saw water levels rise at least that much, and others had relatively small changes.

They studied trends from 1980 to the present in 542 aquifers, for which they had long-term data, and found that declines have worsened or accelerated in 51% of those areas.

Various parts of California were among the regions with rapid and accelerating depletion since 2000. They include farming areas in the Cuyama Valley north of Santa Barbara, as well as large portions of the Central Valley — such as the Kaweah, Chowchilla, Northern Kern, Tule and Madera basins — where the agriculture industry draws on groundwater to produce nuts, fruits, hay, vegetables, grains and other crops.

In these areas, the study found, the median rates of water-level decline ranged from about 2 feet to more than 4 feet per year.

Other places where depletion has accelerated include parts of the western United States — such as the High Plains — Iran, Chile and South Africa.

“The fact that groundwater depletion has been accelerating in such a large number of food-producing regions underscores the critical links between food and water security, and that both are at far greater risk around the world than most people realize,” said Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist and professor at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability who was not involved in the study. “This paper should be a wake-up call that far better groundwater management is needed around the world.”

The study found that more than 80% of the regions with accelerating declines in aquifer levels also saw a decrease in precipitation over the last 40 years. And other research has shown that various dry regions of the world have grown drier in recent decades while accumulating greenhouse gases from fossil fuels have pushed temperatures higher.

Scientists say the drier conditions act as a “positive feedback,” driving even more reliance on wells and more depletion.

Famiglietti and other scientists have used NASA satellite measurements — from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, known as GRACE, and GRACE Follow-On missions — to assess how rapidly groundwater is being extracted in the western United States and other regions from South Asia to the Middle East.

While satellites have enabled scientists to map large-scale depletion in food-producing regions, the latest study reveals a more detailed picture with fine-scale data from water-level measurements in wells.

Famiglietti said the study will help improve satellite-based science by “providing an important reality check on the ground.”

“The sheer volume of well data collected over such a long time period makes this a critically important paper for groundwater sustainability,” Famiglietti said.

The study provides the most extensive analysis to date of water levels in wells worldwide. In all, the scientists said they compiled about 300 million water-level measurements during six years of research. Their team included researchers at universities in the U.S., U.K., Switzerland and Saudi Arabia.

As the scientists examined trends in each aquifer, they found significant improvements in some areas.

Water-level declines have slowed in 20% of the aquifers since 2000, while an additional 16% of aquifers saw declines reverse and water levels rise.

The scientists found examples of water levels recovering in parts of Arkansas, New Mexico, Arizona, California and the Thai capital, Bangkok.

In these and other cases, the researchers said, aquifer levels rebounded after decades of declines because of intervention efforts, such as imposing regulatory measures, importing surface water and reducing pumping, or using water transported from rivers to recharge aquifers.

“Whether that action was a supply-side solution, or a demand-side solution, getting to recovery took action,” Perrone said. “These cases suggest room for optimism that groundwater depletion is not inevitable.”

In El Dorado, Ark., a local agency started charging industrial water users a fee for groundwater pumping, which incentivized businesses to develop a pipeline to bring water from a nearby river, and allowed the aquifer to recover.

In Albuquerque, the city dramatically reduced groundwater use by taking advantage of a water transfer from the Colorado River into the Rio Grande Basin, and also started using the imported water for managed aquifer recharge projects, helping to boost water levels.

In Arizona’s Avra Valley, west of Tucson, water diverted from the Colorado River has been used for aquifer replenishment, increasing groundwater levels.

And in parts of California’s Coachella Valley, water levels have risen as flows of imported Colorado River water, transported in canals, have helped ease demands for groundwater and allowed for aquifer recharge.

In these and other cases, Perrone said, recovery is often linked to using an additional source of water.

These supplies from the Colorado River, however, are also under growing strain. Research has shown that global heating has significantly sapped the river’s flow, and efforts to address shortages have included curtailing the use of Colorado River water for replenishing groundwater.

“Surface water transfers in the southwestern U.S. that have helped some of these aquifers recover will certainly be at risk of being cut back as a result of the aridification going on in this region,” Famiglietti said. “This will be especially true for regions that are receiving Colorado River water. It’s going to be a challenge to maintain long-term recovery without significant additional effort.”

In many parts of the U.S. and other countries, groundwater remains poorly managed or entirely unmanaged.

California is gradually implementing the requirements of the state’s 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which aims to address problems of groundwater depletion in many areas by 2040.

In much of the Central Valley, agricultural wells and pumps continue to draw down groundwater levels. The declines have occurred while many growers have continued drilling wells and converting more farmland to lucrative orchards of almonds and pistachios.

Famiglietti said the groundwater crisis in the Central Valley requires stronger measures, such as requiring well owners to measure and report how much they’re using, charging fees based on amounts pumped, and limiting pumping, while also improving irrigation efficiency and promoting more aquifer recharge.

“There’s a whole kitchen sink of things we need to be trying,” Famiglietti said. “It’s important for future generations. It’s important to sustain our groundwater supply so that we can be growing food for generations and generations, not just one.”

The study presents an impressive amount of data and provides a comprehensive examination of groundwater-level data in different aquifers, said Bridget Scanlon, a senior research scientist at the University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences.

Scanlon, who wasn’t involved in the research, has previously studied areas in Arizona and California where the coordinated use of surface water and groundwater, and managed aquifer recharge efforts, have helped reverse declines. She said support from state legislators is critical to expand these efforts.

Areas without access to surface water, such as farming areas in much of Arizona and the southern High Plains, are much more difficult to manage, Scanlon said. Where aquifers continue to rapidly decline, she said, “economics will play an important role in regulating further depletion” as costs increase for pumping from deeper underground and drilling deeper wells.

A tractor plows a field in the Cuyama Valley in October.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

In other parts of the world, the study’s authors found that aquifer levels rose in Bangkok due to measures including pumping fees. A different sort of recovery occurred in Iran’s Abbas-e Sharghi Basin, where water diverted from a dam reversed declines. And depletion slowed in parts of Saudi Arabia, the researchers wrote, “possibly due partly to policies designed to reduce agricultural water demands.”

The scientists wrote that their analysis “illustrates the potential for depleted aquifers to recover, while demonstrating how much work remains to be done to protect groundwater resources.”

The study didn’t assess the volumes of water that have been depleted globally. But other research has found that massive withdrawals from aquifers are having measurable effects on the Earth’s rotation, and that the extracted water is contributing to sea level rise.

Jasechko said he and his colleagues hope their study can help spread information about solutions for California and other regions.

Still, he said, “there are far more cases where things are getting worse than there are cases where things are getting better.”

Newsletter

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

This story originally appeared on LA Times