Drugmakers grilled on the cost of prescription drugs on Capitol Hill Thursday sought to deflect the criticism onto drug-market middlemen who they said are pushing list prices for medications higher.

The chief executives of Johnson & Johnson

JNJ,

Merck & Co.

MRK,

and Bristol Myers Squibb Co.

BMY,

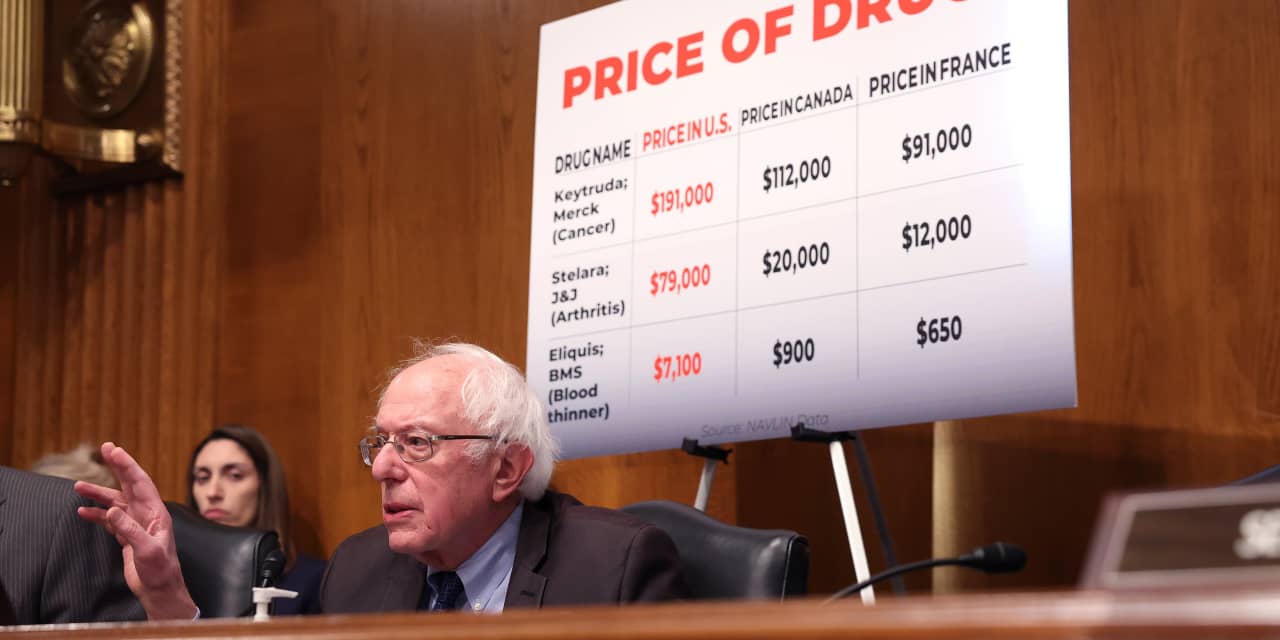

were faced with sharp questioning from Sen. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent, and other members of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee demanding to know why U.S. prescription-drug prices are far higher than prices for the same products overseas.

Top drugmakers “are doing phenomenally well, while Americans cannot afford the cost of the medicines they need,” Sanders said at the hearing, pointing to recent profits, stock buybacks, dividends and executive compensation at the three companies. All three of the drugmakers in recent weeks reported fourth-quarter earnings that topped Wall Street expectations amid strong sales of drugs like Merck’s blockbuster cancer treatment Keytruda and Bristol Myers’s blood thinner Eliquis.

As lawmakers during the three-and-a-half-hour hearing repeatedly highlighted the U.S. list prices of the companies’ top-selling drugs, including Eliquis and Johnson & Johnson’s psoriasis treatment Stelara, the CEOs fired back by suggesting Congress should instead focus on reforms related to pharmacy benefit managers and other intermediaries who they said can collect massive rebates on drugs without passing those savings along to patients.

In 2022, Johnson & Johnson paid out $39 billion in rebates, discounts and fees, almost 60% of the purchase price of its drugs, CEO Joaquin Duato told the committee, adding, “Congress should stop middlemen from taking for themselves the assistance that pharmaceutical companies intend for patients.” While Stelara’s list price is about $79,000 a year, rebates and other discounts cut that price by about 70%, Duato said.

Bristol Myers Squibb, meanwhile, paid out almost $100 billion in rebates and discounts over the past five years, with most of that tied to Eliquis, CEO Chris Boerner told the committee. While the drugmaker sets the list price for the drug, he said, that price “is driven up by the incentives of intermediaries.” When the drugmaker can’t reach an agreement with a pharmacy benefit manager on the rebate, he said, “they take [the drug] off the formulary,” or the list of covered drugs, leaving patients without access to the medication.

At Merck, the diabetes drug Januvia has a list price of $6,900 per year, but Merck only realizes a net price of $690, CEO Robert Davis told the committee. The rest of the money goes to “middlemen,” he said, “into the system as a whole.”

The pharmacy benefit manager industry was not represented at the hearing. Asked to comment on the executives’ statements Wednesday, the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, a trade group, pointed to its statement issued Wednesday ahead of the hearing, saying that “lawmakers should challenge any attempt by drug company executives to evade responsibility for the high prices they alone set, and the anti-competitive tactics used to extend monopolies, which keep competitor products out of the market and drug prices high.”

The hearing comes as more than 80% of Americans say drug prices are unreasonable, according to health-policy research nonprofit KFF, and majorities of Republicans, Democrats and independents say there is not enough government regulation to limit prescription-drug prices.

Narrowing the gap between U.S. and overseas drug prices has become a key talking point for some members of both major political parties. If elected, former President Donald Trump has pledged to revive his “most-favored nation” drug-pricing model, which would have linked prices for drugs under Medicare Part B to prices paid overseas but which was scrapped by the Biden administration. Under the policy, the federal government “will tell Big Pharma that we will only pay the best price they offer to foreign nations, who have been taking advantage of us for so long,” Trump said in a video posted to his campaign website last year. “The United States is tired of getting ripped off.”

Although other countries effectively “free ride off the innovation stimulated by the American market,” introducing European-style pricing policies to the U.S. is not the answer, Darius Lakdawalla, research director at the University of Southern California’s Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, said in a written statement to the committee. Such a step would reduce Americans’ life expectancy by over half a year, because a tradeoff between innovation and affordability means that U.S. consumers get to access newer drugs earlier and more often than people in other countries, Lakdawalla told the committee.

Congress could remove incentives for the system to favor higher list prices by requiring that intermediaries’ revenue streams be delinked from the price of medicines or, alternatively, by requiring that discounts provided by drugmakers be passed through to patients at the pharmacy counter, the pharmaceutical executives said Thursday.

Lawmakers have put forth a number of recent proposals to overhaul the pharmacy benefit manager industry, and some on Thursday suggested that those intermediaries should remain the focus. “We may not have the right bad guys here,” Sen. Mitt Romney said at the hearing, adding that pharmacy benefit managers want “higher and higher list prices.”

In a written statement to the committee, Merck’s Davis also outlined what can happen when pharmaceutical companies try to cut list prices. When Merck launched a hepatitis C medicine, Zepatier, at a list price 42% below that of the drug commonly used at the time, pharmacy benefit managers and plans were reluctant to add Zepatier to their formularies, Davis said in the statement. Cutting the list price by another 60% didn’t boost the uptake, he said, adding that “lower list prices can result in reduced access for patients.”

The role of patents in keeping drug prices high was also in the spotlight Thursday. While Merck’s key patents on Keytruda expire in 2028, the company currently has 37 years of patent protection on the drug, including on a subcutaneous formulation that, if approved, could replace the current intravenous version, Tahir Amin, CEO of the Initiative for Medicines, Access and Knowledge, a nonprofit that advocates for drug-pricing reform, said in a written statement to the committee. Switching to the subcutaneous form could “lengthen Merck’s market monopoly on the drug,” Amin said.

Merck said in a statement to MarketWatch that “there doesn’t have to be a ‘one size fits all’ approach to the route of administration for a cancer drug with 39 [Food and Drug Administration] approved uses, and many potential future indications still in clinical development.” If a subcutaneous version of Keytruda is approved by the FDA, the company said, Merck has no current plans to take the current intravenous version off the market.

This story originally appeared on Marketwatch