After years of rapid expansion, California’s booming EV market may be showing signs of fatigue as high vehicle prices, unreliable charging networks and other consumer headaches appear to dampen enthusiasm for zero-emission vehicles.

For the first time in more than a decade, electric vehicle sales dropped significantly in the last half of 2023. There are even signs that Californians may be growing tired of Tesla — or at least weary of its outspoken chief executive, Elon Musk — as state Tesla sales fell 10% in the final quarter of last year.

It’s unclear whether the declines are a mere blip or the beginning of a downward trend, but the news is already raising questions about California’s ability to meet its ambitious climate goals, including a pledge to ban the sale of new gasoline- and diesel-powered cars and light trucks by 2035.

“It’s an interesting time for the automakers and consumers,” said Greg Bannon, director of automotive engineering at AAA. “The government and automakers have spent billions on something consumers may not want.”

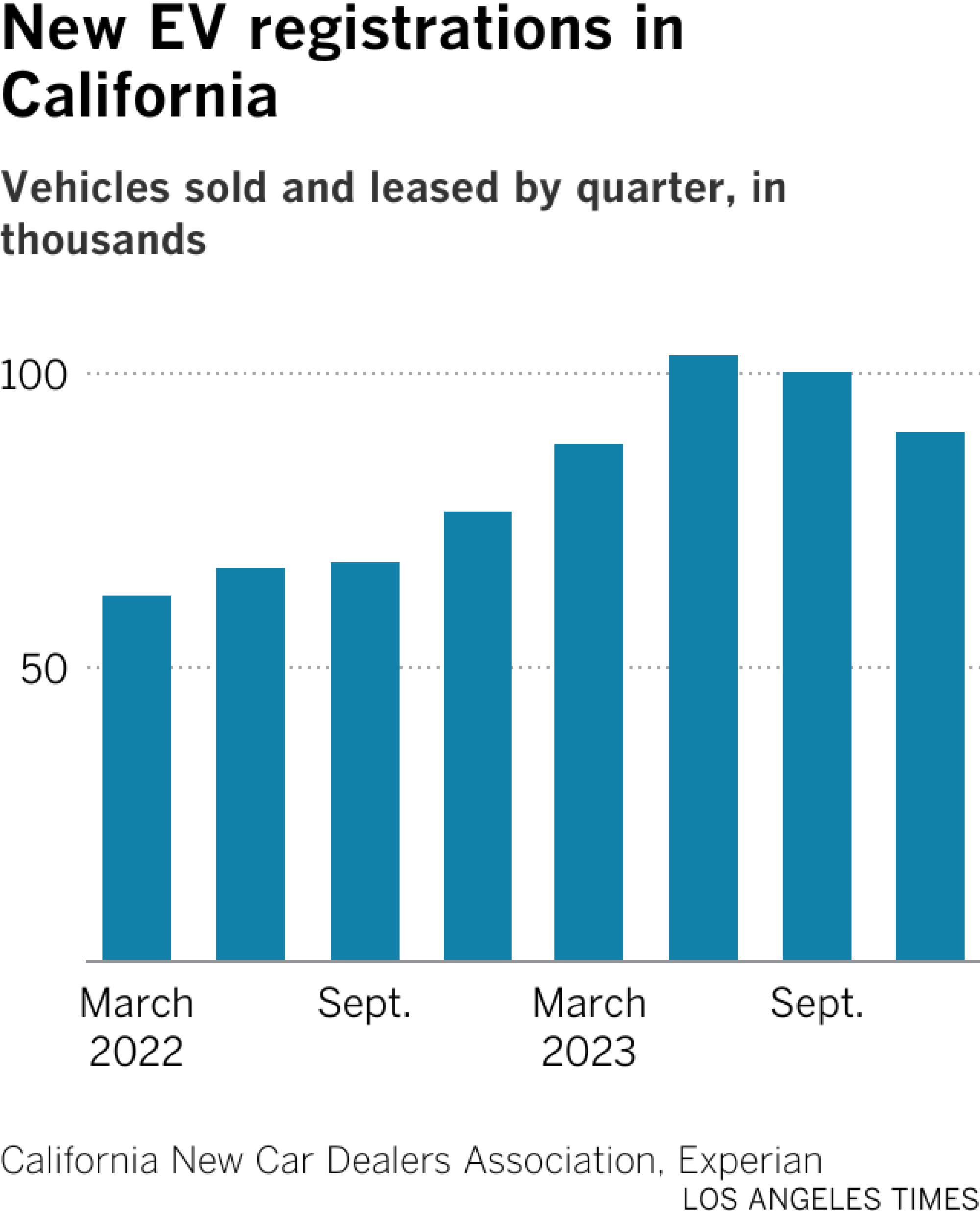

Sales of all-electric cars and light trucks in California had started off strong in 2023, rising 48% in the first half of the year compared with a year earlier. By that time, California EV sales numbered roughly 190,807 — or slightly more than a quarter of all EV sales in the nation, according to the California New Car Dealers Assn.

But it’s what happened in the second half of last year though that’s generating jitters. Sales in the third quarter fell by 2,840 from the previous period — the first quarterly drop for EVs in California since the Tesla Model S was introduced in 2012. And the fourth quarter was even worse: Sales dropped 10.2%, from 100,151 to 89,933.

“There are real challenges,” said Corey Cantor, EV analyst at Bloomberg BNEF, an energy research firm. “Growth year-on-year for 2023 was really impressive, but watching the first half of this year will be important.”

Propelled by the sales success of Tesla, and boosted by electric vehicles from other automakers entering the market, consumer acceptance of EVs had seemed like a given until recently. In fact, robust sales growth is a key assumption in the state’s zero-emission vehicle plan.

Currently, there are 1.4 million electric vehicles on the road in California, and EVs make up 20.1% of all new car sales. Under the no-gas mandate, zero-emission vehicles must account for 35% of all new vehicle sales by model year 2026.

“It’s conceivable we can get to 35% in two years, but it’s going to be difficult to get there,” said Brian Maas, president of the California car dealers association.

Why the slowdown? Market analysts and survey takers point to several issues: unreliable or insufficient public chargers, high vehicle prices, high interest rates and confusing government incentive programs.

Some also theorize that an aging product line coupled with a steady stream of controversial pronouncements by Tesla’s Musk have turned off consumers — particularly in Democratic-heavy counties where EVs are most popular.

Nationally, EV sales growth also has slowed as automakers such as Ford and General Motors cut back — at least temporarily — on EV and battery production plans. Hertz, the rental car giant, is also pulling back on plans to shift heavily toward EVs. Hertz several years ago announced plans to buy 100,000 Teslas but is now selling off its EV fleet.

Hyundai-Genesis North America Chief Executive Jose Munoz with the all-electric Hyundai Ioniq 5.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Cantor, the BNEF analyst, said that although recent sales figures are worrisome, there’s plenty of momentum behind the EV transition, as evidenced by government mandates around the globe and massive investments by motor vehicle manufacturers and their suppliers.

Those investments total $616 billion globally over five years, according to consulting firm AlixPartners.

But plenty of speed bumps and roadblocks could impede the EV transition. Here are some of the biggest challenges:

Undependable chargers

Public charging is notoriously unreliable. As The Times reported in January, the state government is contending with an undependable charging system that, according to studies from academic researchers and market analysts, can be counted on to malfunction at least 20% of the time. That has provoked an outcry from EV owners who can lose hours a day locating working chargers and then waiting in line to use them.

The Tesla Supercharger station in Kettleman City, Calif.

(Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

California has doled out $1 billion to EV charger companies thus far, with more billions to come. But the California Energy Commission, which hands out the cash grants for charger installation, has only now decided to collect reliability statistics. It’s also mulling over how to hold the charger companies accountable for performance. The charger companies, including Electrify America, ChargePoint, and EV Go, have promised to improve.

Too few public chargers

Even if they were reliable, there aren’t enough chargers to go around. EV sales have outpaced public charger installation. The energy commission reports 93,855 publicly accessible chargers are in place throughout the state, including 10,000 fast chargers. That’s far short of the 250,000 chargers that the state has targeted by 2025. The state estimates that by 2035, 2.1 million chargers will be needed.

There are bright spots however: Some Tesla Supercharger stations — the number is not yet clear — will be opened up to non-Tesla vehicles over the next few years. The federal government is spending $5 billion nationally to put fast chargers on major highways at 50-mile intervals. California will receive $384 million.

A Tesla Supercharger Station in Kettleman City, Calif.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

Seven major automakers have also teamed up to build a North American charging network of their own, called Ionna. The joint venture plans to install at least 30,000 chargers — which would be open to any EV brand — at stations that will provide restrooms, food service and retail stores on site or nearby.

High prices

Although the cost of building EVs continues to drop, it has yet to reach price parity with internal combustion cars and trucks. The average retail price for an EV now is $55,343, compared with $48,247 across all vehicles, according to Kelley Blue Book. Higher interest rates add more price tag pain.

President Biden stops to talk to the media as he drives a Ford F-150 Lightning truck in May 2021.

(Associated Press)

Tesla, which has built more manufacturing capacity than the market demanded, slashed prices last year. That’s caused other EV makers to lower prices in kind — or to keep prices elevated but cut back on production.

Ford has taken that approach with its F-150 Lighting electric pickup truck. Despite glowing reviews in the automotive media, sales have been disappointing. Ford chose to cut planned production in half rather than lose big money on drastic price cuts. Marin Gjaja, head of Ford’s EV arm, recently told stock analysts that the next generation of EVs will be launched “only when they can be profitable.”

Confusing incentives

Government incentives, whether tax credits or cash grants, do help boost EV sales. But as the Biden administration tries to balance EV adoption with a made-in-America industrial policy, federal incentives have become both scarcer and harder to understand.

Depending on whether a car was manufactured in North America or not, and what countries its battery materials were sourced from, tax credits could range from nothing to $3,750 to $7,500. The number of models that qualify for the full federal subsidy has fallen from 17 last year to 8 today.

To further complicate matters, EVs assembled overseas and purchased domestically don’t qualify for tax credits. However, consumers can qualify for federal subsidies if they lease the same vehicle instead. It’s a complicated arrangement that requires close work with a trusted dealer to sort out.

There’s some good news for those who do qualify for a tax credit when they buy an EV. Since Jan.1, buyers don’t have to wait until they file their taxes to benefit — they get the credit upfront as a reduction in purchase price.

In California, EV subsidies were reworked last year. Strict income ceilings were put in place to qualify for help. Poorer buyers will get more incentives; richer buyers, nothing at all. Such an approach addresses equity concerns, but it will take time to assess the affect on EV sales.

Market saturation?

The EV market is far from saturated. In 2023, 15.6 million cars and light trucks were sold in the United States, most of them gasoline. Electric cars accounted for just 7.6% of those sales.

In California, the market share is already up to 20.1%. The ultimate limit on market saturation, theoretically, is 100% in 2035.

But there’s also a market for EV early adopters: those who can afford EVs and buy them because they’re perceived as cool, or like the way they drive, or are deeply concerned about the climate — or all three.

But mainstream buyers — i.e., most car buyers — might be a tougher sell. “A lot of observers agree that early adopters have bought an EV,” said Maas, the California car dealer president. “These vehicles are very expensive for the mass market, and on top of that you have the charging challenges,” he said.

Lower-priced EV models are due to arrive over the next several years, but right now they’re in short supply. In fact, General Motors last year announced that it would stop selling its popular Bolt EV, one of the least expensive EVs on the market, while pushing gigantic battery-powered vehicles such as the Silverado pickup and the 9,000-pound Hummer. Americans have shown a strong preference for bigger vehicles — pickup trucks and SUVs. Those require bigger, heavier and more expensive battery packs — one reason prices remain so high. (Profit margins are much higher on these vehicles too.)

The Musk factor

There’s no survey to prove it, but there’s plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest liberal-leaning California car buyers are done with Elon Musk’s abrasive personality and his stands on political issues. (Ask friends or neighbors who drive a Tesla.)

Elon Musk, chief executive of what was then Twitter, is broadcast on a screen as he speaks at a Miami marketing conference in April 2023.

(Rebecca Blackwell / Associated Press)

LaRaye Lyles, a therapist and consultant in Oakland, was thrilled when she bought a Tesla Model Y a couple of years ago. “I felt very happy when I got the car. I was excited about it. Then I lost the joy of owning a Tesla.”

Musk’s endorsement of the “great replacement theory” championed by white supremacists on X, his hostility toward transgender activism and his general public persona turned her off. “I would absolutely not get a Tesla again, as long as Elon Musk is associated with it,” she said. “In fact, I wish I’d leased this one so I could just give it back.”

Tesla remains a major player in California. Last year, 1 in 8 cars sold, EV or gasoline, was a Tesla. But in the fourth quarter, Tesla sales dived 10%. If enough buyers here are truly fed up enough with Musk to influence their purchasing decisions, Tesla’s sales could continue to suffer.

On the EV front, there’s plenty to watch out for in the year ahead.

This story originally appeared on LA Times