A series of powerful storms brought Los Angeles close to having its wettest February ever recorded.

Another storm is moving in Monday afternoon. Forecasters have been downgrading projections for the storm for days, and it’s looking less and less likely that it will provide enough rain to make history. The latest forecast calls for less than a half an inch of rain through Tuesday, with snow levels hovering around 7,000 feet.

Even so, the last month has been remarkable. Downtown Los Angeles has recorded an incredible 12.56 inches of rain so far this February — a quadrupling of its average February rainfall.

Modern record keeping began in 1877, and the record for the rainiest February was in 1998, when an incredible 13.68 inches of rain fell on downtown L.A., part of a memorable El Niño winter.

Compared to February 1998, California has been relatively lucky in February 2024. The latest storms dumped much rain — resulting in localized damage and destroying at least one home — but at a rate and intensity that did not cause widespread landslides across the state along with the loss of life and destruction that seemed to be a hallmark of many California winters in the 1990s.

In California in 1998, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said, “four weeks of nearly continuous storminess resulted in widespread flooding, mudslides, and agriculture disruptions.”

This February is likely to come up short of being an all-time record breaker.

Only a weak storm is expected starting Monday afternoon that could last through Tuesday. That will be the last storm for February.

(The first storm of March, forecast to arrive on Friday and lasting through the weekend, is expected to be moderate.)

About one-tenth of an inch of rain could fall on downtown L.A. over Monday and Tuesday, according to the National Weather Service office in Oxnard. Generally, most areas are expected to receive less than one-quarter of an inch, but hillside areas might get up to half an inch.

That would end this month with a whimper of a storm — something very different from what California experienced in the February of 1998, which ended with a very powerful one.

Unlike this February’s storms, where the lion’s share came during Feb. 4-6, plus more over the Presidents Day weekend, the February of 26 years ago brought repeated storms with little time to dry off, with the last storm of the month causing some of the worst damage and many deaths.

That included a devastating mudslide that hit homes in Laguna Beach. Glenn Alan Flook, a lanky, athletic 25-year-old, had taken refuge in a neighbor’s home when it was struck by mud. He was thrown through a window as the room collapsed; his body was found wedged beneath a mobile home 50 yards downstream.

Elsewhere in Southern California 26 years ago, two California Highway Patrol officers died in San Luis Obispo County after their car fell into a massive sinkhole as a river eroded a highway. Two Pomona College 19-year-olds heading to class were killed when a eucalyptus tree slammed into their sport utility vehicle.

Northern California was hit hard by landslides in early February 1998. A landslide that destroyed a house in rural San Mateo County killed one person, and another landslide elsewhere in the county damaged a number of homes. With most of the Bay Area receiving double the average rainfall by the midwinter of 1997-98, “a number of slow-moving landslides were activated” that winter and into spring, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

California’s early February storm of 2024 came with nine reported deaths statewide — three in car wrecks; four from falling trees; one person found dead in a river in San Diego County; and a woman who was in hospice care who died after the power went out at her home.

Landslides affected a number of areas earlier this month, destroying one home in the Beverly Crest neighborhood of Los Angeles. Landslides also damaged homes in the San Fernando Valley, the San Gabriel Valley and Baldwin Hills.

The winter of 1997–98 has long been seen as a memorable year because it brought so much rain and came during a very strong El Niño. But total seasonal rainfall isn’t the only factor in explaining particularly costly damage. The “timing of storms within the season, and not the total seasonal rainfall,” matters, as explained by meteorologist Jan Null.

On his Golden Gate Weather Services website, the veteran meteorologist noted that the 1997–98 El Niño rain year wasn’t even among the top 10 costliest in California’s modern record, causing roughly $860 million in damage statewide in 2023 dollars.

The costliest flood season in the modern record actually came during a weak-to-moderate El Niño during the 1994–95 season, resulting in $5 billion in damage statewide, according to Null. That season hit the central California coast particularly hard, even temporarily isolating the Monterey Peninsula as rivers flooded key roads into the area.

Seasons with the worst flood damage occur during “high intensity-short duration” storms that overwhelm flood control systems, Null wrote. The January and March 1995 storms “were both events of extremely high one-day rainfall rates concentrated over a relatively small region,” Null said.

The second-costliest modern flood season was last year, at a cost of $3.5 billion, according to Null, and resulted in at least 22 storm-related deaths, according to a Times tally. There was a weak-to-moderate La Niña that season.

And the third-costliest came during the 1996–97 season, which brought $2.94 billion in damage, when there was neither El Niño nor La Niña, but New Year’s floods fueled by an atmospheric river hit the Central Valley hard.

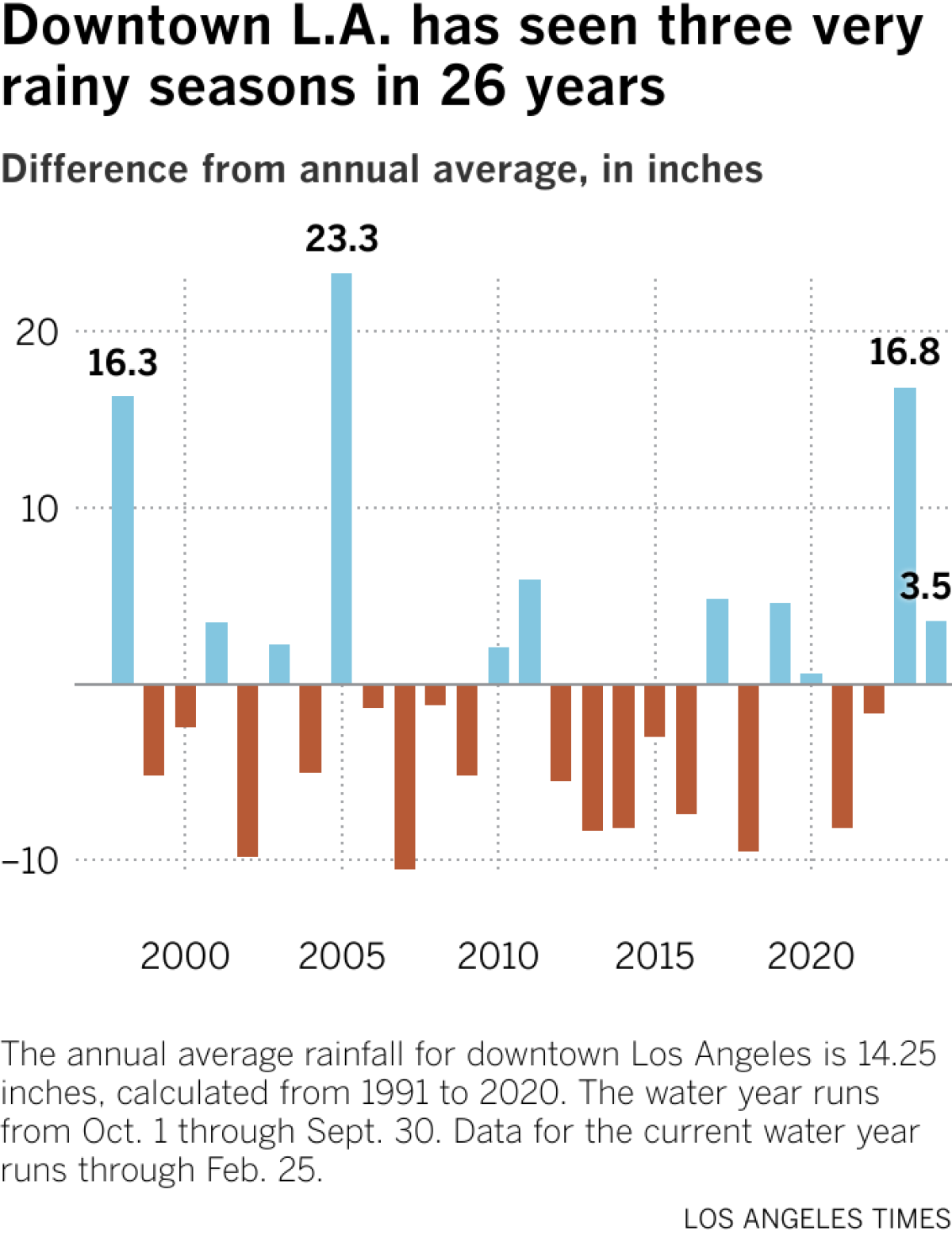

And while it feels like there has seen a lot of rain recently, thus far, downtown L.A. has seen only a little bit above average for the entire year thus far.

As of Sunday, 17.79 inches of rain had fallen on downtown L.A. since the water year began Oct. 1. That’s 3.54 inches more than the annual average of 14.25 inches.

That’s significant, but if there is only very little rain until the water year ends Sept. 30, downtown L.A. would only be a bit above average for the entire year.

For downtown L.A., there have been only three supersized rainy seasons in the past 26 years — for the water years that ended in 1998, 2005 and 2023. In each of those water years, downtown L.A. recorded more than 30 inches of rain, or more than 16 inches above the annual average.

Also important to note is that in the northern Sierra, precipitation for this time of the season is roughly average.

A key benchmark index for monitoring precipitation key to the statewide water supply is known as the northern Sierra eight-station index. It’s important because precipitation that falls on that stretch of California’s mightiest mountain range supplies reservoirs that send water throughout the state.

As of Sunday, the precipitation total in the northern Sierra since Oct. 1 is 32.7 inches — just short of the average of 35 inches at this point in the water year, but nowhere near where it was at this time in the 2016–17 drought-busting season.

During that record-breaking season that ended a devastating five-year drought, by late February 2017, more than 75 inches of precipitation had already fallen in the northern Sierra, well on its way to finish the water year at 94.7 inches.

During last year’s impressive season, by late February, more than 40 inches had fallen, and by the end of the water year, 66.6 inches of precipitation had fallen in the northern Sierra.

The average for the northern Sierra eight-station precipitation index for the end of the water year is 53.2 inches.

This story originally appeared on LA Times