The team gathered at 4th and Crocker streets and headed south, into the blue-tented netherworld of social collapse, armed with life-saving drug-overdose kits and injectable, long-acting anti-psychotic medication.

“We’re trying very aggressive treatment on the streets,” said Dr. Susan Partovi. “Housing definitely saves your life, but there’s a small sub-group of people who won’t accept housing because of their mental illness.”

She figures that if she administers medication that lasts a month and can help stabilize patients — with their consent — they’ve got a chance.

“They don’t think there’s anything wrong, and they think they don’t need housing,” Partovi said. “They don’t think rationally, and so once you treat their delusions and their irrationality, they start to realize, ‘Oh, I do need resources.’ ”

Partovi, who began practicing street medicine in 2007 in Santa Monica, has never been shy about her lack of patience with the official response to the entrenched humanitarian crisis. In 2017, I shadowed her as she walked through Skid Row with County Supervisor Kathryn Barger, advocating for broader authority to assist those in obvious acute mental and physical distress, even if they refused help, and despite opposition from civil rights attorneys and others.

By administering long-acting meds, Partovi—author of the just-published “Renegade M.D.: A Doctor’s Stories From the Streets”—is once again pushing boundaries. She’s acting out of a belief that her approach is medically sound, and with frustration sharpened by her street-level view of the countless bureaucratic cracks and canyons in the system. She’s driven, too, by an uncompromising compassion for homeless people who are so sick, she can sometimes predict who will die next.

Critics might say a person in the throes of impairment isn’t competent to give consent for a month-long dose of medication, and that such meds are neither a panacea nor a substitute for intensive ongoing case management. But to Partovi, the slow pace of intervention — along with multiple daily deaths on the streets — add up to a human rights violation and a moral failure, so she’s stepping into the breach.

But she’s not a psychiatrist, and her street medicine team’s approach is not fully embraced by the L.A. County Department of Mental Health. DMH has psychiatric street medicine teams operating in several parts of the county. The Skid Row unit —which is led by Dr. Shayan Rab and injcludes psychiatric nurses, social workers and addiction counselors, and sometimes conducts sidewalk court hearings for those who resist treatment — was featured in a September 2022 article by my colleague Doug Smith.

Dr. Susan Partovi, left, and Dr. Steven Hochman talk to a woman during their medical outreach.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Dr. Curley Bonds, chief medical officer of the department, says DMH psychiatrists first establish a working relationship with the client and invest time in determining a clinical history, including prescribed medications and dosage. It can be difficult, he said, to distinguish between psychosis and the effects of street drugs like methamphetamine, but trained psychiatrists have an advantage over doctors with other specialties. Treatment would ordinarily begin with short-term oral medication, Bonds said, to establish the “efficacy and tolerability of the agent.”

Only then would long-acting injectables be an option, he continued, but even then, the civil rights of the patient would have to be a consideration.

“We are more cautious about making sure there is informed consent and … we really want to respect a person’s autonomy for decision-making,” Bonds said. Despite procedural differences and quibbles over the Partovi team’s approach, Bonds added, “I don’t want to put us at odds with them … because what they are doing is important work.”

A glance at the reality on the streets of Los Angeles makes clear that far more help and substantially greater urgency are badly needed. And Partovi is not alone in practicing what she calls “low barrier bridge psychiatry.”

Dr. Coley King, director of homeless healthcare at the Venice Family Clinic, is not a psychiatrist, either. But as a street medic in L.A., the national capital of homelessness, he works in what is essentially an outdoor mental hospital, with tents instead of beds. King treats mental illness and whatever else he sees — and what, often, no one else is treating.

He told me he has used both short-term and long-term anti-psychotics, depending on the situation. The risks posed by medication are not as great, he said, as the risk of being homeless, sick and untreated.

“The need is so dire, and the patients are dying at such a young age, and the lack of available psychiatry is so marked,” said King, who leads a street medicine team through Westside streets four days a week and often works with a psychiatric nurse practitioner. “We’re not doing this in any sort of cavalier fashion. We’re doing it very thoughtfully with a mind to knowing our medications and knowing our diagnosis and treatment are based on a ton of experience and a lot of exposure to working side-by-side with psychiatrists in the field.”

In 2020, I wrote about a formerly homeless Santa Monica woman whose life had been turned around after King treated her for her addiction and physical and mental ailments. The treatment included a long-acting injection the woman agreed to, and when I met her, she was living in a hotel before moving into housing arranged by the outreach team.

::

When I met with Partovi last month on Skid Row, her team consisted of Dr. Steven Hochman, an addiction specialist; David Dadiomov, director of USC’s psychiatry pharmacy program; and social worker Sylvia Meza. It was Meza who established this nonprofit outreach team — it’s called SUDIS, for Substance Use Disorder Integrated Services — and brought in Partovi as medical director last year.

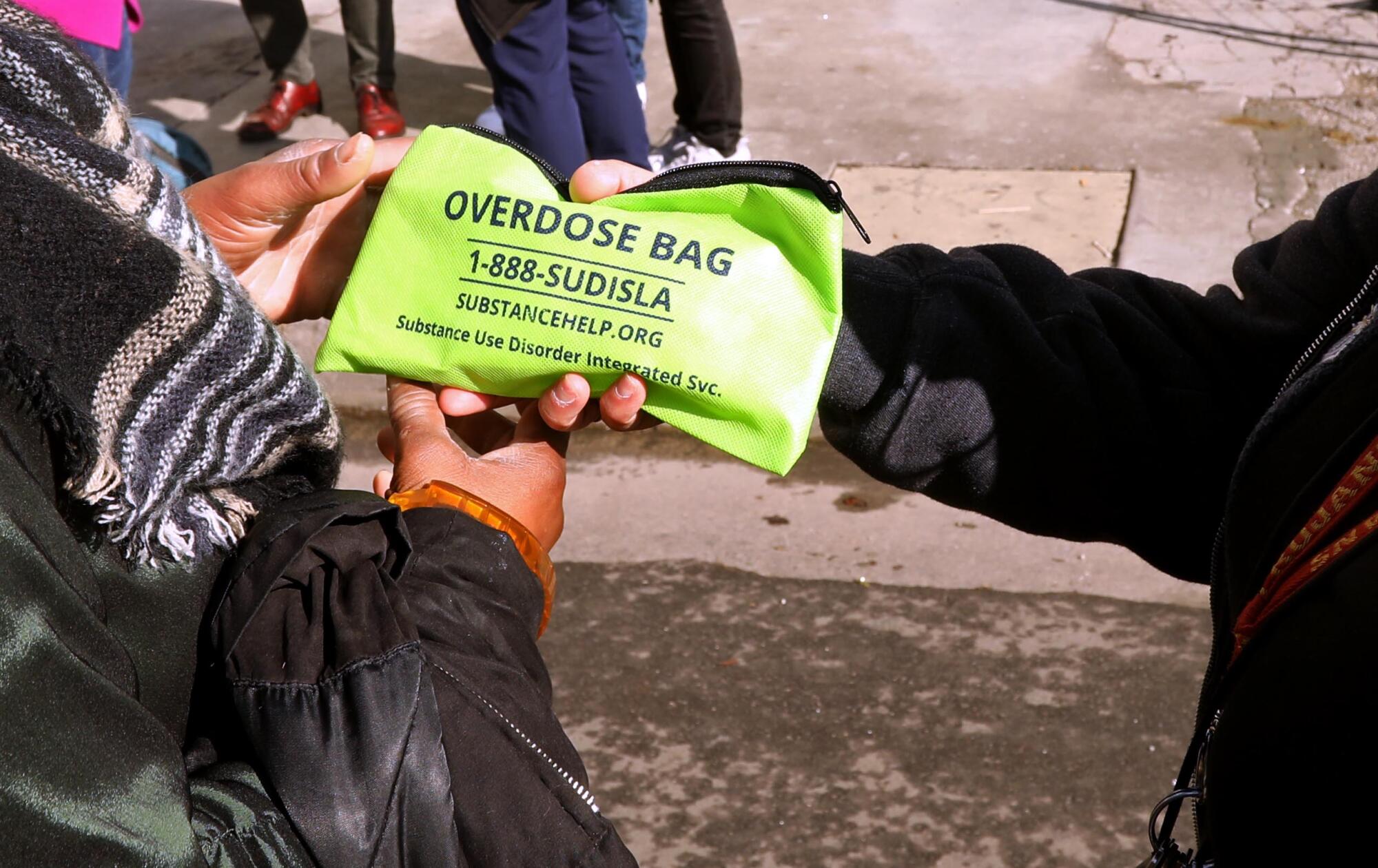

Overdose bags contain Naloxone — a medication designed to reverse an opioid overdose — fentanyl strips to detect the presence of fentanyl and reading materials about avoiding overdose.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

As someone who works the aging beat, I was struck by how many of the people we encountered were late middle age and beyond. Partovi estimated that about 50% of the people served by the team are 50 and older.

“They got caught up in Skid Row when they were young and were never able to get out of it,” Meza said. “Skid Row is like bondage. People are trapped in there. They have this poverty mentality where they feel like they can’t get out, but they can. It’s just about motivating them to see the cup as half full and not half empty.”

A gray-haired man crossed the street before us, and just up ahead, 63-year-old Israel stood near a tent, not far from a woman named Diane, who said she was 60 and was caring for her two cats, Gold and Silver, along with two dogs owned by a woman who’s in jail.

“That’s French Fry,” Partovi said as one of the dogs, a white terrier, crossed the street.

She knew the dog’s name because that’s how outreach works— you get to know people, their routines, their histories, even their pets. Neither Diane nor Israel was interested in medication on this day, but a connection was made, the first step in building trust.

Hochman spoke to Israel in Spanish and English, letting him know he’d be back again, and that medication was available. He told me the outreach team tries to determine a patient’s medical history, and at times does prescribe short-term medication if there are concerns about tolerability. But people often lose their daily medication, Hochman said. Or they forget to take it. Or it gets stolen, or swept away in storms or street-cleaning sweeps. A month-long dose can up the chances of turning things around.

On Crocker Street, where the team distributed Narcan kits to slow the epidemic of overdose deaths, Meza was joking with a 68-year-old man when we noticed that Partovi, a half block away, was waving for the team to join her.

Dr. Steven Hochman, left, Dr. Susan Partovi and Sylvia Meza check on the well-being of a man in downtown Los Angeles.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

The doctor had spotted a woman she thought would be a candidate for an injection. Amanda, 51, said she had been diagnosed with two psychiatric conditions. She listed her most recent medications and said she wanted something to treat her depression.

Partovi asked several questions, including whether Amanda had a history of adverse reactions. Partovi has a network of psychiatrists she can consult, but she didn’t think she needed to in this case. She informed Amanda that with the injection, she’d be medicated for a month. Amanda gave her approval.

“I’m gonna hold your hand,” Meza said as Partovi rolled up Amanda’s sleeve and poked a syringe into the soft tissue of her right shoulder.

“We want to do this every month,” Partovi said as Amanda grimaced from the sting.

“Sorry, sorry, sorry, sorry, almost done,” Partovi said before adding: “OK, now you’re good.”

Partovi said that in the best scenarios, the “word salad” dissipates, patients express themselves more clearly, and they make better decisions about recovery. “In my experience, once they get their mental health stabilized, then they want to work on substance abuse,” she said.

I asked how she can distinguish between mental illness and the effects of drug use.

“We’re not treating a diagnosis,” she said. “We’re treating symptoms. If someone is having psychiatric symptoms, the literature shows that whether it’s meth-related or organic schizophrenia, the anti-psychotics are going to work. That’s been my experience as well.”

Among the homeless people of Skid Row or anywhere else, the back stories are usually long and messy narratives involving childhood trauma, domestic abuse, sexual assault, chronic disease, poverty, incarceration, a lack of affordable housing, mental illness and self-medication with increasingly dangerous street drugs.

Amanda said she’d been homeless since 2017 after doing some jail time and that she couldn’t recall having a place of her own. Meza promised Amanda she would investigate options for housing and other services.

“Do not lose my number,” Meza said, handing Amanda her business card. “This is my personal cell number.”

They posed together for a photo, and then the team kept moving, getting approval for injections from two more clients over the next 20 minutes.

I first connected with Partovi many years ago, after I’d met a homeless Juilliard-trained street musician whose career had been derailed after a diagnosis of mental illness. In full disclosure, at her request, I interviewed Partovi about her work and “Renegade M.D.” at her book-launch party last month.

In the book — a compelling and personal front-lines look at who becomes homeless and why, complete with triumphs and tragedies and an unflinching examination of a fragmented system that is a often a barrier to recovery — Partovi says that as a Westside teenager, she traveled to a leprosy clinic in Mexico with a Christian service group and medical team. She knew then what she wanted to do with her life.

“I made the commitment to become a doctor and focus on patients who experience the worlds of poverty and injustice,” she writes.

In 2007, while working as a street doctor in Santa Monica, she came upon “a woman who looked to be in her 80s but was probably younger. Living on the streets ages people quickly.”

She thought of her own grandmother, who had passed away in her 90s.

“If my grandmother had wanted to panhandle on the Promenade in her flannel nightgown, I would have picked her up … and thrown her into my car. … I would never allow my family member to live on the streets. … Why do we, as a society, allow it?”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

This story originally appeared on LA Times