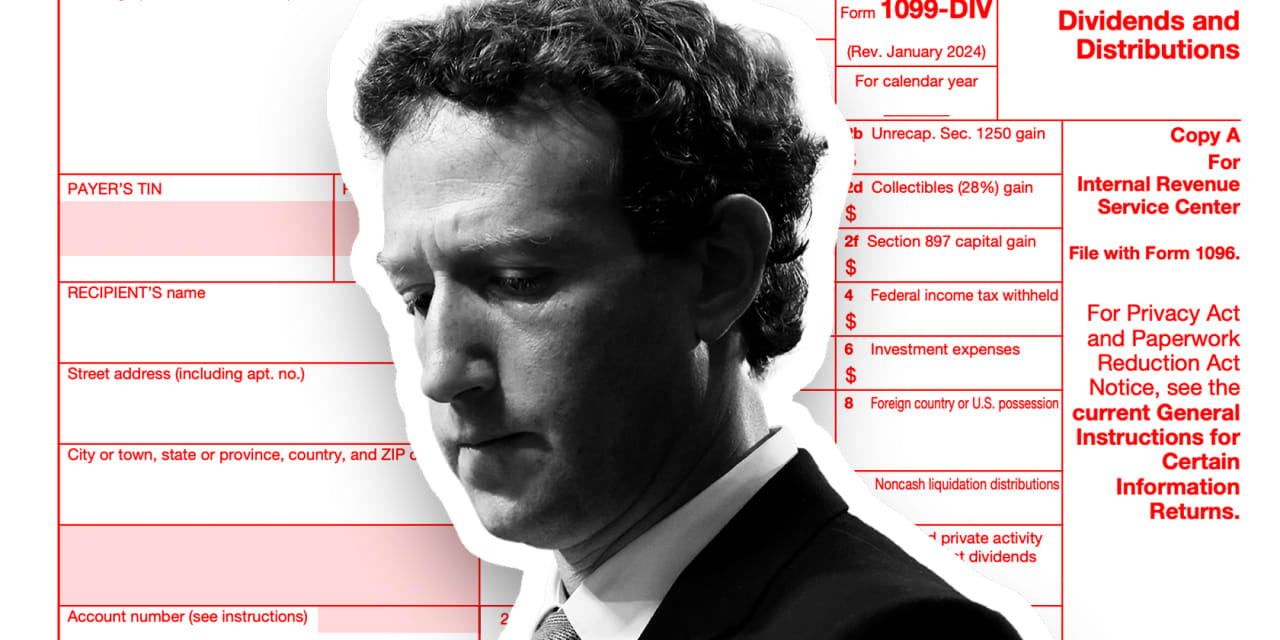

Mark Zuckerberg delighted Meta shareholders and Wall Street this week with news of the social media giant’s first-ever dividend.

The IRS may also be happy, now that it’s staring at millions in taxes on the Meta stock dividends bound for Zuckerberg’s portfolio.

Zuckerberg, the CEO of Meta Platforms Inc.

META,

is poised to make $700 million in dividends yearly. He owns nearly 350 million shares, according to FactSet, and the company will start paying a quarterly dividend of 50 cents a share.

That would yield nearly $167 million in federal taxes yearly, after a qualified-dividend tax of 20% and another 3.8% tax on the investment returns of rich households, two accounting experts said.

California income taxes of 13.3% on the dividends could cost Zuckerberg another $93.1 million, said Andrew Belnap, an accounting professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business.

All in, that’s a combined $259.7 million in federal and state taxes annually on the Meta dividends, Belnap estimated.

For context, U.S. taxpayers reported over $285 billion in qualified-dividend income to the IRS though mid-November 2023, according to agency statistics. Nearly 30 million tax returns reported qualified dividends through that time.

Meta said it plans a quarterly cash dividend going forward, with the first such payment in March.

Meta shares soared 20.5% on Friday, ending with a record-high close of $474.99. The Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

S&P 500

SPX

and Nasdaq Composite

COMP

all closed higher Friday.

‘Zuck is getting a major break’

Meta announced the dividend payment in its earnings results Thursday, on the same week that Americans began filing their income taxes.

A look at Zuckerberg’s dividends and their tax implications offer a peek at the debate about the varying ways wages and wealth are taxed.

“Zuck is getting a major break,” said Andrew Schmidt, an accounting professor at North Carolina State University’s Poole School of Management who also crunched the numbers for MarketWatch.

Approximately $167 million “seems like a high tax bill,” he said. But if Zuckerberg received the $700 million as a straight salary, Schmidt estimated he’d be looking at a roughly $259 million tax bill on the wages after they were taxed at the top marginal rate of 37%.

Federal income tax brackets run from 10% to 37%.

Meanwhile, the IRS taxes qualified dividends and capital gains at 0%, 15% and 20%, depending on income and household status. The net investment income tax adds another 3.8% for individuals making at least $200,000 or married couples worth $250,000.

For federal and state taxes on the Meta dividends, Zuckerberg would face a combined rate of 37.1%, Belnap noted. “His tax rate on this is actually fairly high,” he said.

The gap in tax rates on income derived from wages and investments “has been a big criticism with U.S. tax policy,” Schmidt said, especially as lawmakers look for ways to come up with more tax revenue.

Regular retail investors enjoy the same preferential rates on capital gains and dividends as the top 1% of taxpayers, Schmidt added. The issue is that those dividends and stock profits are a smaller part of their income while salaries, taxed at higher rates, are a bigger proportion.

Belnap noted that California’s state tax rules don’t provide special treatment to dividends.

Zuckerberg received a $1 base salary in 2022, a figure that hasn’t changed in several years. He is now worth $142 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, making him the fifth-richest person in the world.

Meta did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Taxes on the Meta dividends will not be something Zuckerberg, or any Meta shareholders big or small, need to deal with until next year’s tax season, Belnap and Schmidt observed.

But as taxpayers amass their 1099-DIV forms on dividend income, IRS figures show that it’s mostly upper-echelon taxpayers reaping the rewards on the preferential rates for qualified dividends.

Households worth at least $1 million accounted for 40% of the approximate $285.3 billion in qualified dividends reported through mid-November, according to agency figures.

For less affluent investors, “it’s usually a nice supplement, but I’d say very few people are living off dividends,” Belnap said.

This story originally appeared on Marketwatch