Since 1982, Sallie Reeves and her husband have lived atop a serene Rancho Palos Verdes canyon, overlooking the sparkling Pacific Ocean and Catalina Island, with little reason to worry about the slow-moving landslide complex beneath their feet.

“We’ve been here 41 years, never had a problem,” said Reeves, 80.

In just the last month, however, their Portuguese Bend home has started shifting under stress from intensifying land movement: Cracks have snaked up their walls, cupboards can no longer close, doorways have split at the seams and brick pavers are separating.

“We had no damage until one month ago,” Reeves said. “Now we’re making repairs.”

Sallie Reeves looks out at the view from her back deck at the home she has lived in for 41 years in the Portuguese Bend area of Rancho Palos Verdes on Wednesday.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

It’s far from the worst damage in the neighborhood, yet it’s a clear sign of the landslides’ escalation — fueled by back-to-back winters of heavy rains that experts say have not only accelerated the shifting, but also brought damage to more areas.

“What’s happening is unprecedented,” Mike Phipps, Rancho Palos Verdes’ contracted geologist, said this month after reviewing more than 16 years of data. “We haven’t seen this kind of movement in the upper areas of the landslide in the whole history of monitoring this landslide.”

The Portuguese Bend complex hasn’t been plagued by the sudden and violent shifts commonly associated with the word “landslide.” Instead, the ground has moved for years at a uniquely glacial pace, making it one of the most studied landslides in the nation. But the recent scale and rate of its movement have officials and residents on edge.

In the gated Portuguese Bend community where Reeves lives, just north of Palos Verdes Drive South, many of the neighborhood’s hilly streets are now lined with sandbags, dotted with orange cones or blocked by signs that warn of “landslide damage.” Where the road is not torn open by new cracks, there’s often fresh pavement trying to band-aid the latest splits or plastic tarps covering nearby fissures.

In the Seaview neighborhood of Rancho Palos Verdes, streets are closed and damage is being mitigated as new land movement exacerbated by recent storms has caused large cracks in pavement and damage.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

“This just gets worse by the day,” Reeves said on a recent walk through Cinnamon Lane, which she called a new ground zero for landslide movement.

Some areas in the landslide complex have struggled with slope movement for years — but now the issue has turned into a more widespread, and escalating, crisis.

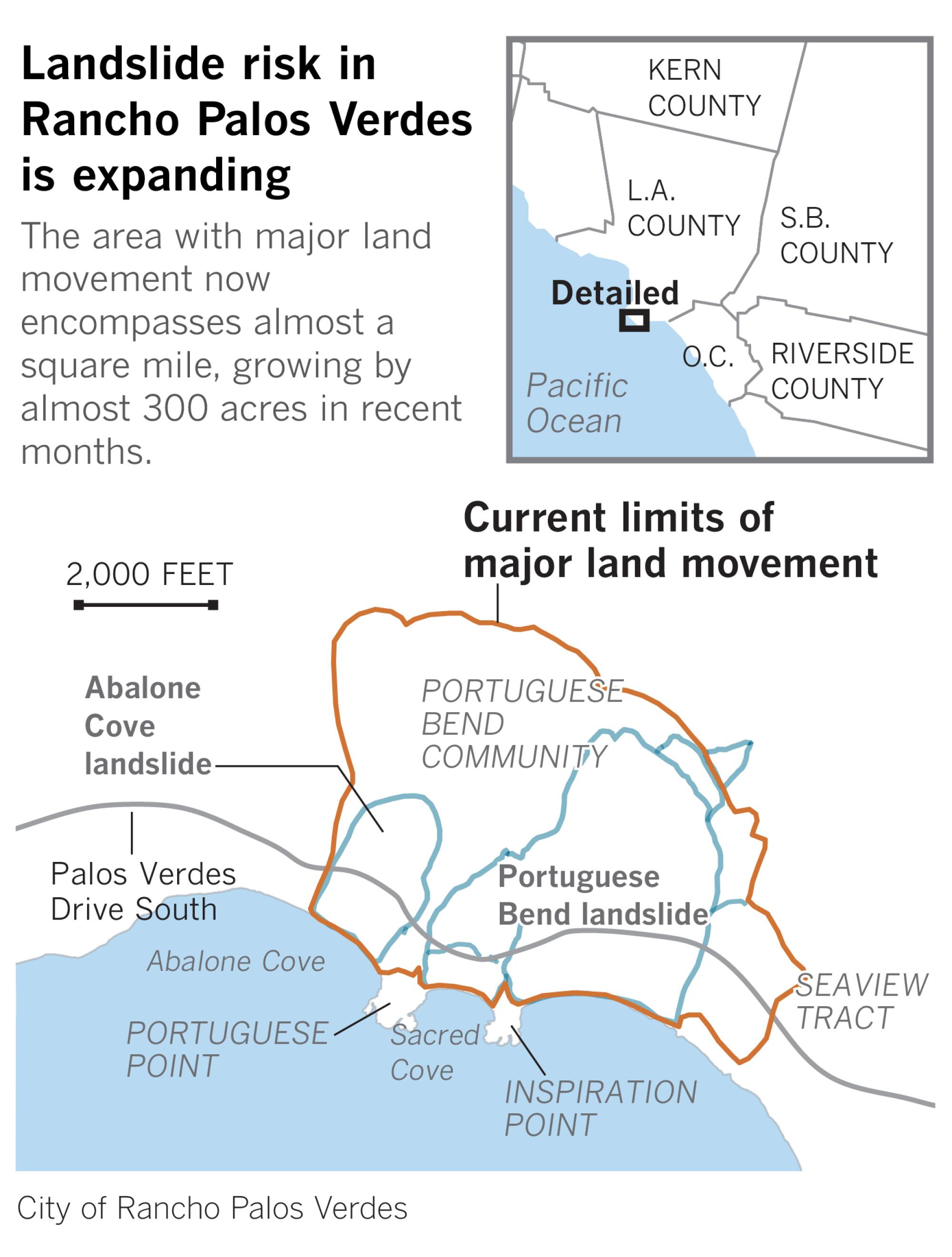

Major landslide movement is now occurring across almost 700 acres, or slightly over a square mile, Phipps estimated. That’s a 75% increase over the area that had seen major movement over the last few decades. And the rate of movement in recent months is three or four times that of prior analyses, he said, with further acceleration expected.

“I’m worried about the immediate effects today on infrastructure — the roads, the utilities, anything that’s buried,” Phipps said at a City Council meeting this month. “I’m just worried that we’re going to start losing roads … people are going to start losing access to their private properties.”

(Paul Duginski / Los Angeles Times)

Officials know that water is fueling the increasing land movement — infiltrating layers of clay, softening it — but stopping moisture from entering the ground is extremely difficult during repeated, record-setting rainstorms. Residents are facing another wet winter storm this week, heightening concerns that new rainfall could exacerbate what’s quickly becoming an emergency situation.

Often, landslides are triggered months after a rainy season. Increasingly, however, the rain’s effects are almost immediate, Portuguese Bend residents said.

“It rains and our house is moving,” said Caitlin McKay, whose home sits not far from where Reeves pointed out the landslide’s ground zero. McKay and her husband were unaware of any major movement issues when they purchased their home just two years ago; now they’re desperately trying to retrofit their walls, ceilings and foundation to ensure their young family’s safety.

‘It may not be enough’

In September, two new homes were red-tagged in the Seaview neighborhood — a community just southeast of Portuguese Bend — amid growing land movement, prompting city leaders to declare a local emergency. Now, officials are seeking an emergency declaration from the state, which they hope could bolster their fight.

There are approximately 400 homes in the area of the expanding landslides, with dozens already seeing damage, Phipps said. More than eight miles of trails have closed across Portuguese Bend Reserve, Filiorum Reserve, Abalone Cove Reserve and Forrestal Reserve, according to city park officials, because of toppled utility poles, massive fissures, fallen rocks and dangerous dropoffs.

The Wayfarers Chapel — designed by Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. and recently named a national historic landmark — announced its indefinite closure this week due to “accelerated land movement in our local area.”

Wayfarers Chapel rests nestled among the trees in Palos Verdes on Nov. 30, 2022.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

The neighborhoods where Reeves and McKay live around the Portuguese Bend Riding Club have moved an average of 4 feet in the last 15 months, Phipps said. Many of these areas have previously moved less than a foot, if at all, during similar stretches, the geologist reported.

The ancient complex includes four historically active landslides, dubbed the Portuguese Bend, Abalone Cove, Klondike Canyon and Beach Club landslides. The oldest and largest, Portuguese Bend, was activated in 1956, starting the land’s slow descent to the sea. After initial shifts ruined about 130 homes, officials have been able to stave off extreme damage with close monitoring, ongoing remediation and a growing inventory of de-watering wells, which pump out water from underground.

Possibly the only bright spot in this ongoing crisis, experts say, is that even with accelerating movement, the region is not expected to morph into a catastrophic landslide, as occurred last summer in nearby Rolling Hills Estates. In that surprising and disastrous event, which officials have said was probably caused by heavy winter rains, eight homes crashed down a canyon wall when the slope rapidly dropped 45 feet, destroying them and rendering several others unsafe to inhabit.

But the Rancho Palos Verdes community is still facing a laundry list of escalating issues. More land movement has meant more ruined roadways, water and gas leaks and property damage — all requiring frequent and intensive repairs, often with hefty price tags. That’s become too much even for a wealthy community like this one.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency recently awarded the city a $23.3-million grant to fund a long-term remediation project aimed at slowing the landslide, but that work is not expected to start until 2025.

A teddy bear decoration is perched along rerouted water lines on Exultant Drive where land movement exacerbated by recent storms has caused large cracks in pavement and damage to nearby homes in the 4300 block of Dauntless Drive on Feb. 9 in Rancho Palos Verdes.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

In the meantime, the city and local landslide abatement districts have put in six new de-watering wells, and local utilities have increased monitoring and started moving some lines above ground.

“I think we’re gonna see a tremendous benefit from all that,” Phipps said. “But, you know, we’re right in the middle of winter. We still got the six, seven weeks of what are usually the wettest months in Southern California…. It may not be enough.”

The City Council plans to meet next week to discuss ways to expedite projects in the works.

“Everybody is very concerned that, a) we have enough money to get through the year and b) that we can somehow arrest the sliding,” said Gordon Leon, chair of the Abalone Cove Landslide Abatement District, which operates 16 de-watering wells and will soon bring the six new ones online. The 16 currently pump out 130,000 gallons of water a day, he said.

But operating on a yearly budget of only about $250,000, the district has already gone through its reserves covering maintenance costs and the price of new wells, he said.

“It’s going to be tight getting from where we are today through the end of the year,” he said, “And we’re at a time when the landslide is moving at record speeds.”

Nevertheless, they stay

Yet residents across the neighborhoods most affected remain hopeful. Some are holding out for more federal disaster aid; others want to see drainage improved, the canyon lined more effectively or utility projects prioritized.

Many just hope for no more rain.

But despite a collaborative focus on the ongoing problem, most of those solutions are still far from becoming reality.

“I just don’t know if a lot of these houses [have multiple] years to spare,” McKay said. With every water main break — of which there have been many lately — water floods their streets and hillsides, adding to the saturated soils and landslides’ fragile layers, which she believes has to be worsening the problem.

Front steps have cracked and dropped nearly a foot at a home on Dauntless Drive in the Seaview neighborhood of Rancho Palos Verdes.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

“Everything takes so long,” said Julian McKay, Caitlin McKay’s husband. “This should have been dealt with five to 10 years ago, not in the middle of the crisis.”

And they are seeing the effects particularly clearly, the couple said.

“The movement on our property is insane,” said Julian McKay.

Since purchasing their home in 2022, they’ve learned that it sits on a fissure, which has continued to open and move with each rainstorm.

Within a few months of their arrival, small problems became more drastic: Ceiling cracks grew to an inch wide, the garage started separating from the house, their patio was sinking and a portion of their backyard plunged “as if a wave was rolling through,” Julian McKay said.

They are now doing intensive retrofitting work that has cost more than $50,000, they estimate, and they’re just at the beginning.

But with plans for a stabilized foundation and more pliable ceilings and walls, he and his wife are confident they will be able to keep themselves and their 6-month-old daughter safe for years to come. They have no plans to leave the area, despite its unstable ground and mounting repair fees.

“It’s such a magical neighborhood,” Julian McKay said. “When the movement slows, it’s back to being amazing.”

Sallie Reeves looks out at the view from her back deck at the home she has lived in for 41 years in the Portuguese Bend area of Rancho Palos Verdes on Wednesday.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Reeves worries about home values dipping as the landslide crisis drags on, yet the neighborhood remains prime real estate. In the last two years, several homes have sold across the Portuguese Bend community, according to Zillow data, including at least one just last month and one in late 2023 — even though the increasing landslide movement was well-documented.

“This is paradise, there is no place like Portuguese Bend,” Reeves said, looking out on her lush garden that overlooks the ocean. “I’m leaving in a box, that’s the only way I’m leaving here. And I’m not alone in how I feel about that.”

This story originally appeared on LA Times