After nearly 100 days at sea, the crew had given up. Since early September, they had logged nearly 12,000 miles aboard the Offshore Surveyor, crisscrossing the equator near the 180th meridian. Now a few days past Thanksgiving, the time had come to move on.

Amelia Earhart poses with her Lockheed Vega, the aircraft that helped many pilots in the late 1920s and 1930s set flying records. The Vega could fly fast and had a long range, which is why Earhart chose it to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean in 1932.

(Bettmann Archive)

They had worked hard under a tropical sun, days becoming weeks, a familiar routine offloading their unmanned submersible and watching as its sonar became their eyes on the ocean floor, recording all that it saw.

There’d been hiccups along the way. Crew had gotten sick. The underwater camera had broken, and after one dive, the data had come back presumably corrupted.

But the team of Deep Sea Vision hadn’t let any of that get in the way. They were out to solve the greatest aviation mystery of all: the disappearance of Amelia Earhart on July 2, 1937, during her epic flight around the world.

For the record:

11:19 a.m. March 13, 2024An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified in some instances, including photo captions, the research vessel Offshore Surveyor as the Offshore Explorer.

Never mind that over the years others had tried in vain to find some evidence of her fate: a faded photograph perhaps, a long-lost letter, some scraps of her plane.

Deep Sea Vision’s chief executive officer, Tony Romeo, a former real estate entrepreneur out of Charleston, S.C., had a plan.

Toward the end of the expedition, the crew had not found Amelia Earhart’s plane, and Craig Wallace and Tony Romeo, on the right, took to Zoom to talk with navigational consultant and Earhart expert Gary LaPook. (Courtesy Deep Sea Vision)

He had studied the maps, read the history and come up with the money to try to prove that Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, had miscalculated their location, run out of gas and perished after ditching their plane in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Proof would be the watery grave of Earhart’s twin-engine Lockheed Electra.

But by early December, Deep Sea Vision had nothing. Steaming away from their hopes toward their next destination, American Samoa, Romeo tried not to be too discouraged. He was having dinner with his crew, and the sun was setting on another beautiful day at sea.

Soon he would be with his family, sharing stories of this adventure and being teased for the beard he had grown while away. As for Earhart? Well, who knows? Maybe she had been abducted by aliens after all.

Then he heard someone calling. Craig Wallace, chief of operations, poked his head into the galley.

“Hey, you guys have to take a look at this.”

Not another technical glitch, Romeo thought.

She flew east to meet the dawn and never returned. Yet in death, Amelia Earhart is still with us. Aviator, feminist, adventurer, who rose to dizzying heights of celebrity in the 1930s, she was to her American moment what Taylor Swift is to ours.

Her stage was the sky, and her songs the records she set: first as a woman, flying alone across the Atlantic and nonstop across the United States; then among all others, flying alone from Hawaii to California and from Los Angeles to Mexico City and then to New Jersey.

Earhart owned at least three Lockheed Vegas. In 1935, she flew the aircraft alone from Honolulu to Oakland and a few months later by herself from Los Angeles to Mexico City and then to Newark, N.J.

( Associated Press)

“She represents freedom, dreaming big, adventurousness, seeking out the unknown,” said Jane Mendelsohn, who captured the heroine’s complicated mystique in a novel, “I Was Amelia Earhart.”

Earhart first earned her wings above the open fields of Los Angeles, wowing weekend crowds at airshows with her youth, her elegance and daring. The 1920s had found a superstar, who with her tousled hair, leather jacket, scarf and khakis, buoyed the world through the Depression.

She had long dreamed of circumnavigating the globe, a “shining adventure,” as she wrote, “perhaps encouraging other women toward greater independence of thought and action.” She began her journey on May 20, flying out of Oakland, with Burbank her first overnight.

Her final radio transmissions two months later en route to a critical fuel stop, Howland Island — but a speck in the middle of the Pacific — still haunt:

We must be on you but cannot see you — but gas is running low — have been unable to reach you by radio — we are flying at 1,000 feet.

A framed photo of Amelia Earhart in 1937, along with goggles she was wearing during her first plane crash, displayed in 2011 at Clars Auction Gallery in Oakland.

(Ben Margot / Associated Press)

For six days, she was a banner headline in the New York Times, all shock and disbelief. She was 39 years old.

“It’s the perfect riddle. It has just enough information to get you excited and not quite enough to get it solved,” said Romeo, 43, whose obsession with Earhart dates to childhood.

His father, a commercial airline pilot, set the hook with tales of her adventures. When Romeo was in fifth grade, he and a friend performed in a school skit, dramatizing a page from her life. The friend played a reporter and Romeo played Earhart, just before she vanished.

We live in an age where two truths are inescapable: The past is never past, and popular culture abhors a vacuum. Since disappearing, Earhart keeps surfacing, born aloft on wild postulations from a cottage industry staffed with history buffs, aviation nerds and undersea explorers.

Some say she survived: that the Japanese rescued her and Noonan; that she was taken to Saipan to broadcast Tokyo Rose-like pronouncements during the war; or that she lived far from the spotlight of fame as a housewife in New Jersey.

Years later when a shred of aircraft aluminum and the rubber heel from a woman’s shoe were found on an island 400 miles from Earhart’s destination, she was imagined to have been a castaway.

Standing beside her Lockheed Electra during a refueling stop in Khartoum, Sudan, on June 13, 1937, Earhart, with a scarf around her neck, speaks with several unidentified people. Less than three weeks later, she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, would be missing.

(Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

Still other searchers argue that she perished after running out of gas and landing on water. Millions of dollars have been spent combing the depths for her Electra, to no avail.

Romeo followed Wallace up the stairs to the forecastle. The Offshore Surveyor, a 110-foot research vessel, was a charter out of Papua New Guinea, and its bridge had a long settee and a table where the crew had set up a bank of computer monitors for tracking the submersible and assessing its findings.

Wallace went to his computer. He had been organizing the data and came across the file from Oct. 8 — Day 32 at sea — which they hadn’t initially been able to open. They presumed it was corrupted.

Other members of the expedition joined them. They had been called to the computer many times before to look at suspicious objects that ultimately didn’t match the Electra’s dimensions.

From the start, their submersible — a $9-million Hugin 6000 — had performed exceptionally well, running untethered for 36-hour stretches about three miles beneath them. They named it Miss Millie Pollywog, a portmanteau of Earhart’s nickname and sailor’s slang for someone who hasn’t crossed the Equator.

Nothing escaped its Doppler, its magnetometer, echo sounder and side scan sonar as it stored hours of imagery on a 10-terabyte hard drive that gave Wallace and Romeo the experience of soaring 50 feet above the ocean floor.

The crew crowded around Wallace. He’d been able to recover the data they thought had been lost.

1

2

3

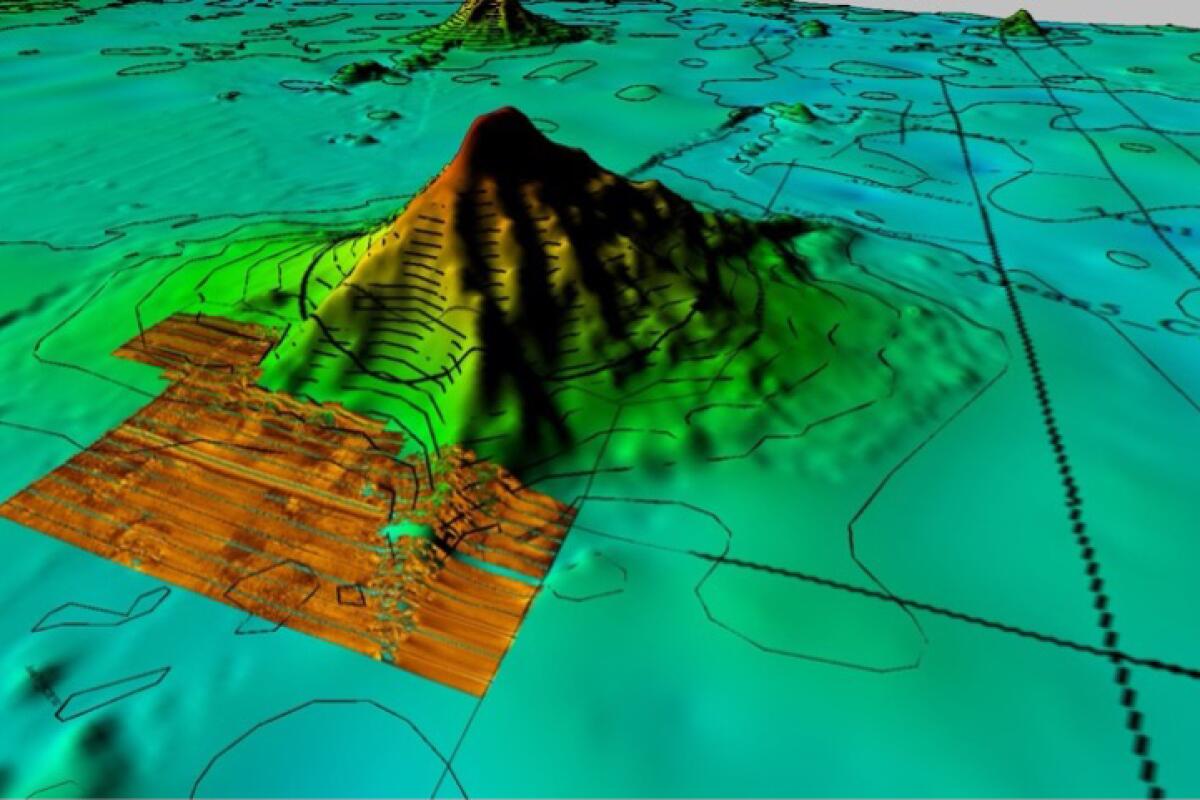

1. Howland Island is a mountain in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. This bathymetric image mapped by the submersible shows a portion of the seafloor at the base of the mountain, in brown. 2. Launched from the stern of the Offshore Surveyor, the unmanned submersible provided the crew with eyes on the seafloor. Working almost 3 miles deep, the vehicle took nearly 90 minutes to reach the bottom. 3. Crew from Deep Sea Vision — from left, Corey Friend, John Haig, Harald Aagedal and Craig Wallace — follow the submersible from the bridge of the Offshore Surveyor. Black-out curtains and red lighting make it easier to look at the monitors. (Courtesy Deep Sea Vision)

They had put to sea three months before at a cost of around $15,000 a day. Six of them operated the vessel. Nine others, including a producer and camera operator, were Romeo’s crew for a documentary with the working title: “Why Not Us?”

“Why can’t six random guys solve aviation’s greatest riddle?” said Romeo. “We’re no Robert Ballards. We’re no James Camerons. We’re just six guys who love the story and put together a business to solve it.”

Wallace hit play.

Romeo got the idea to search for Earhart when he and his son were magnet fishing the Charleston waterways during the pandemic, recovering random pieces of metal from the shallows, a pastime they had read about in the Wall Street Journal.

After retrieving so much fishing gear, Romeo wondered if a string of powerful magnets could pull up something bigger, like a sunken plane. He bounced the idea off his brother Lloyd, a pilot who lives in Temecula. They both agreed it was crazy.

But Romeo shifted his focus to autonomous underwater vehicles and sonar, which are prohibitively expensive. But at the time, he was selling his business.

With interest rates and inflation rising — and the office market falling — he knew he had to pivot. Since retiring from the Air Force in 2008, he had been moving fast — first creating and selling a residential real estate app, then managing commercial properties — and he was ready to get out.

So he bought a fancy Norwegian submersible for $9 million, learned how it worked, set aside another $2 million for the expedition and said goodbye to his wife and two children before taking off for the South Pacific, armed with the idea that Noonan hadn’t calculated a critical variable in longitude when they crossed the International Date Line on their way to Howland Island.

Crews offload supplies at Howland Island from an unidentified vessel. The island, approximately halfway between Papua New Guinea and Hawaii, was favored as a fueling stop for Earhart in her flight across the Pacific Ocean.

(Bettmann Archive)

The theory had seemed plausible.

But after coming up with nothing, he wasn’t so sure.

Wallace clicked the mouse, and the image on the monitor began to move.

The ocean floor on Day 32 came to life as a grainy black and yellow image scrolling down the screen like the credit roll at the end of a movie.

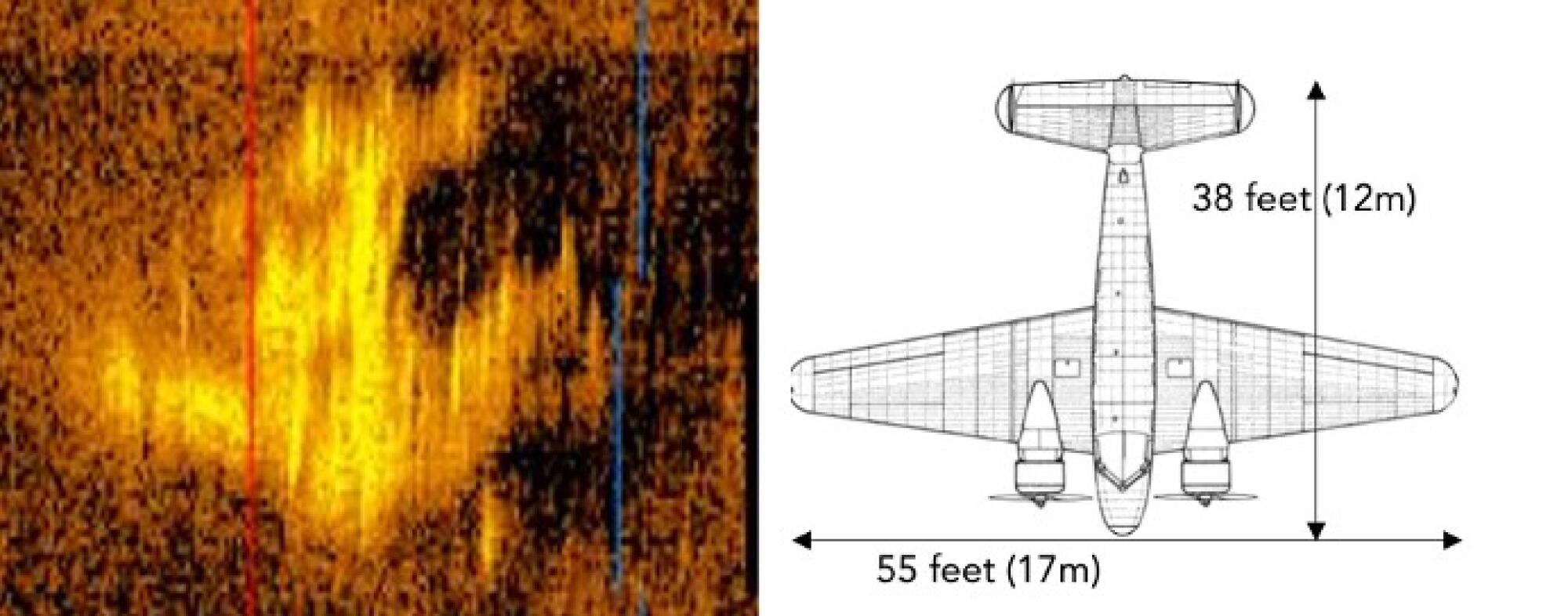

Wallace adjusted for brightness. He had applied filters that sorted for objects with straight lines and the same dimensions as the Lockheed Electra.

A brighter yellow shape emerged as a cross. The image was marred by interference. The submersible had caught it at a distance of about 750 feet.

Wallace froze the screen.

“Holy s—,” Romeo said.

There it was. He could even make out what he thought were the twin vertical stabilizers on the tail.

He felt a chill, not quite goosebumps, just the awareness, surreal actually, that this was the plane, seen for the first time since 1937.

Wallace replayed the image, and the crew began to talk. They knew that sonar can distort and that the mind can see what it wants, and still they needed to take precautions.

An image captured by sonar from an unmanned submersible is suggestive of Amelia Earhart’s twin-engine Lockheed Electra. The dimensions seem to match.

(Deep Sea Vision)

They had a checklist for just this moment, and the first step was to shut down the ship’s Starlink satellite connection. They wanted no one aboard to send or receive messages.

The confidentiality of their discovery — and its location — was paramount.

An estimated 3 million wrecks litter the seafloor, ranging from Nazi gold ships and Spanish galleons to ordinary cargo ships. As technology for both finding and plundering these vessels has grown more sophisticated, more companies have entered the field, increasing competition.

Never mind the tragedy of the Titan imploding last June on its way to the Titanic, killing all on board. Many firms employ unmanned autonomous vehicles for explorations just as vivid.

In 2018, a London-based company set its sights on a $70-million reward for Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, which had gone off the radar in 2014 somewhere in the Indian Ocean, with 239 people aboard. While the airliner was not found, the company did discover other shipwrecks, whose locations could be sold to treasure hunters.

In 2022, a deep-sea mapping company and a film crew collected more than 700,000 images of the Titanic and its debris field. The expedition was framed as an attempt “to write the proper science of the Titanic” with the prospect of one day monetizing a virtual tour of the ship.

While Earhart’s plane, like Ernest Shackleton’s recently found Endurance, has no material worth, its value is incalculable, measured by both the prestige of finding it and by its enduring fame, which helps explain this deep obsession.

One undersea exploration company, Nauticos, has mounted four expeditions covering a total of nearly 5,000 square miles, north and west of Howland Island, and come back with nothing.

After a day and a half of work, the unmanned submersible returns to the Offshore Surveyor. A winch pulls the vehicle up a hydraulic platform onto the deck. (Deep Sea Vision)

Its president and founder, Dave Jourdan, is skeptical of Deep Sea Vision’s claim.

“From the information that we have, there is no way to say exactly what it is,” said Jourdan. “It could be an aircraft. It could be a pile of rocks that looks like an aircraft. We just can’t tell. If it were the Electra, there are certain features we would expect to see: big engines, straight wings (not swept-back wings), closer dimensions.”

Those discrepancies can be explained, he said, “but the more discrepancies you have, the more explanation is required.”

John Gregg, whose Signal Hill-based company has conducted underwater surveys for development projects off Australia and Africa, calls Deep Sea Vision’s work “credible.” He also argues that there’s more at stake than just finding the Electra.

“These guys want the big splash to move their brand along,” said Gregg, “and to even raise the possibility that they have found it, they have accomplished their goal. They have gotten on everyone’s playlist.”

Hypnotized by the image, Romeo felt a pang of regret.

They had had it all along, 68 days earlier, if only they had taken the time to retrieve the file.

But he realized that the delay played to their advantage. The coordinates of Earhart’s plane were miles behind them. No one would be able to retrace their course.

He relaxed. The news would get out eventually, so the team decided to scrub the image of sensitive data and release it.

Wallace grabbed a bottle of whiskey, vintage 1937, the year Earhart disappeared. A toast seemed in order. But they held back. The Pacific was a graveyard of lost planes, and they wanted undeniable confirmation.

“Of course, it could be another aircraft. Until this is confirmed, skepticism is fair and needed,” said Romeo, who hopes to provide the ending to this chapter of history.

“It is a story that needs closure,” he said.

But will the mystery of Amelia Earhart ever be closed?

“Many people have wanted to be the first to know and solve the mystery,” said biographer Susan Butler, whose “East to the Dawn: The Life of Amelia Earhart” covers the breadth of her accomplishments. “But I never understood why, when the most fascinating thing was the most wonderful life she led.”

Mendelsohn, the novelist, has come to understand Earhart’s life and death as a Rorschach upon which the culture projects its unspoken aspirations, its unbridled desires no matter the risk, the danger or prospect of failure.

“I don’t know if finding out what actually happened will change any of that,” said Mendelsohn. “Even if we find the plane, I don’t think we will ever unravel the mystery of Amelia Earhart.”

Romeo is busy working out the logistics for returning to that remote corner of the Pacific in 2025.

He is confident that the Electra is so well-preserved in the icy depths that a photograph will show its radio registration — NR16020 — lettered on its wings.

Then comes the task of its retrieval.

For Romeo to make a claim in maritime court, he would have to provide some physical evidence. Not wanting to damage the plane, he is hoping photographs will do.

Then comes the question of sensitivity. While Earhart had no children, there are surviving relatives on her sister’s side of the family.

Earhart had initially planned to fly westward around the world. Her first stop was Honolulu, where she and Noonan were photographed on March 20, 1937. Problems with the aircraft forced them to cancel their attempt. Two months later they tried again, flying eastward.

(Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

“We plan on working with them,” Romeo said.

Lastly, there are logistics. To bring the plane to the surface, it needs to be structurally sound, and Romeo suspects it is, since Earhart was a skilled pilot who likely landed the plane on the water rather than crashing.

Then it’s a matter of getting a net under it, a task that “requires an engineering skill set that we don’t have.”

Still, Romeo is resolved.

“She belongs in the Smithsonian,” he said. “She needs to come home.”

This story originally appeared on LA Times