Garth Hudson, the stoic multi-instrumentalist and co-founder of the Canadian roots-rock group the Band, died Tuesday at a nursing facility in his adopted hometown of Woodstock, N.Y. He was 87.

His death was confirmed by the Toronto Star, which attributed the news to Hudson’s estate executor and said he “passed away peacefully in his sleep.” Hudson was the last surviving original member of the Band following Robbie Robertson’s death at age 80 in 2023.

Across a lifetime of music, Hudson — whose bushy beard, professorial demeanor and musical chops added a scholarly gravitas to the Band through his work on electric organ, accordion and saxophone — played with artists including Bob Dylan, Emmylou Harris, Neil Diamond, Norah Jones, Neko Case and Ringo Starr.

Though his bandmates did most of the talking in interviews and onstage, Hudson’s musical textures, many inspired by old Canadian and American folk songs, were essential elements of the Band’s sound on classic-rock standards including “The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and “The Shape I’m In.”

Famously, Hudson served as tape recorder operator and de facto engineer when, in 1967, Dylan moved to Saugerties, N.Y., to recover from a motorcycle crash and began woodshedding sessions with Hudson’s bandmates Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Levon Helm and Richard Manuel in the basement of a house they dubbed Big Pink. Hudson’s recordings served as the basis of both for the seminal Dylan and the Band album “The Basement Tapes,” officially released in 1975, and “Music From Big Pink,” the Band’s 1967 debut album.

Hudson’s stately bearing belied his roots as a rock ’n’ roller. Anyone who has seen his work in “The Last Waltz,” Martin Scorsese’s 1978 documentary on the Band’s final performance, will recall Hudson’s skills. Looking more like a 19th century senator than a late-1960s hitmaker, during the film he approached the microphone for an alto sax solo in “It Makes No Difference” as if stepping to a lectern to give a speech. When he did, he held the floor with effortless elocution.

“Different musical styles are just like different languages,” Hudson told Canada’s Globe and Mail in a rare 2002 interview. “I’m able to play a lot of instruments so I can learn the languages.” He added, “It’s all country music; it just depends on what country we’re talking about.”

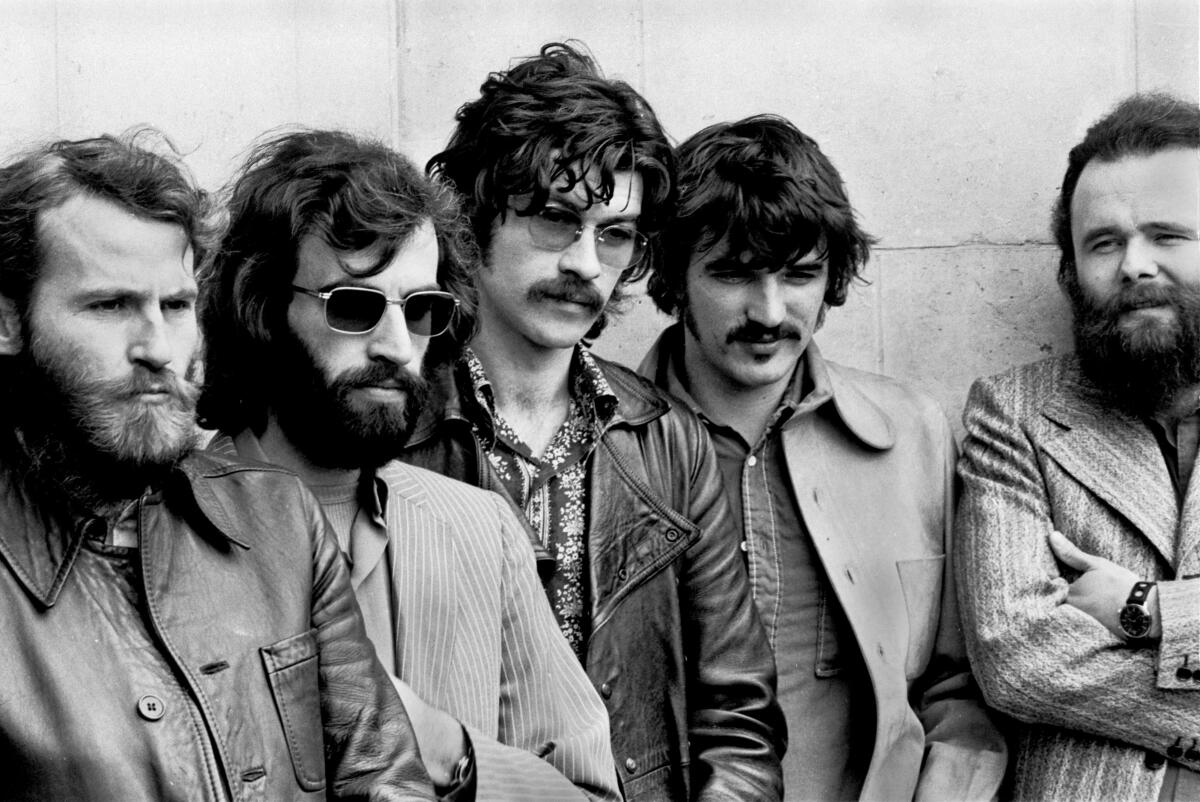

The Band, from left, Garth Hudson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Levon Helm and Robbie Robertson.

(GAB Archive / Redferns)

Born on Aug. 2, 1937, in Windsor, Ontario, Eric Garth Hudson was the son of a musically inclined father, Fred Hudson, who was a fighter pilot in World War I before becoming a farm inspector, and an accordion- and piano-playing mother, Olive Hudson, who started teaching her son both instruments when he was a child.

In addition to formal training, like many adolescents at the time Hudson’s musical tastes were informed by Alan Freed’s “Moondog Matinee” rock ’n’ roll radio show, which was broadcast from Cleveland. “That’s when I realized there were people over there having more fun than I was,” Hudson said, as quoted in Greil Marcus’ tome “Mystery Train.“ Hudson joined his first band when he was 12 and spent his teens playing piano and saxophone in rock and jazz outfits.

In 1957, he co-founded the Silhouettes, which morphed into Paul London and the Capers. The band occasionally ventured south to Chicago and Detroit, and even traveled west during one tour to play the famed jazz club the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach. “We’d played a couple of months before the Border Patrol told us to go home,” Hudson, who spoke with a measured Northern drawl when he bothered to talk in public at all, told the Globe and Mail. “They told us we had to get permanent work visas, which at that time they mostly gave to hockey players and wrestlers.”

In late 1950s Toronto, Hudson met the four other members of the Band when they were hired to tour with rock ’n’ roll singer Ronnie Hawkins. Within a few years, the Hawks gelled into a studied, tight backing band. As they gained momentum, they left Hawkins in 1963 to tour on their own, trekking through southern Canada and across the border to clubs on the East Coast. Dylan connected with the future Band during one of these stops and invited them to tour Europe with him. During these tours, Dylan officially “went electric” for half of each concert.

Garth Hudson performs during “The Last Waltz” on Nov. 25, 1976 in San Francisco.

(Ed Perlstein / Redferns)

That’s Hudson powering his trademark Lowrey organ through Dylan’s searing performance of “Like a Rolling Stone” at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, England, on May 17, 1966. He hit those overpowering first notes after an angry folk-loving fan had screamed “Judas!” at Dylan for betraying his folk roots. That outburst was due in no small part to Hudson’s pipe-rattling organ fills.

Hudson and the rest of the Band descended on Dylan’s home in Saugerties the next year. Each morning, the Band would awaken at Big Pink and prepare for rehearsals. Hudson went down early to ensure the recorder was prepared for Dylan’s arrival. When the day’s sessions started, Hudson sat in a corner near his organ and hit “record.”

“The wonderful thing in working with Dylan was the imagery in his lyrics, and I was allowed to play with these words,” Hudson told Keyboard magazine in 1983. “I didn’t do it incessantly. I didn’t try to catch the clouds or the moon or whatever it might be every time. But I would try and introduce some little thing at one point a third of the way through a song, which might have something to do with the words that were going by.”

Hudson added that when he was starting out he test-drove the more popular Hammond B-3 organ, but he was drawn to a model made by a smaller company, Lowrey. “The Lowrey had enough bite, and I could make it distort enough, to fit in with what we were doing.” The early models, continued Hudson, erupted with “a great distorted sound when you turned everything up.”

Hudson recorded 1968’s “Music From Big Pink” just as he’d done the Dylan sessions. Writer Marcus described the album in “Mystery Train“ with a sense of reverence: “Flowing through their music were spirits of acceptance and desire, rebellion and awe, raw excitement, good sex, open humor, a magic feel for history — a determination to find plurality and drama in an America we had met too often as a monolith.”

That album and its 1969 follow-up, “The Band,” cemented their reputation among the critics, but it failed to register in a youth market then obsessed with LSD and psychedelic music. When the sound the Band helped forge, country-rock, became a commercial powerhouse a few years later, they watched as acts including the Eagles, Lynyrd Skynyrd and countryman Neil Young soared to the top of the charts. The Band released five studio albums between 1970 and 1976. None was a runaway commercial success, but the musicians remained a powerful live band. Dylan invited them to embark on a 1974 joint tour, which later that year was the basis for Dylan’s first live album, “Before the Flood.”

The Band, left, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko and Garth Hudson in London, June 1971.

(Gijsbert Hanekroot / Redferns)

In the mid-1970s, Hudson and most of his bandmates — drummer Helm divided his time between L.A. and Arkansas — moved to Malibu to help create another legendary studio, Shangri-La. With Dylan investing alongside the band, they leased a house, allegedly a former bordello, and turned it into a state-of-the-art recording studio. Hudson bought a nearby property he dubbed Big Oak Basin Dude Ranch. By then, though, the Band had been together for nearly 15 years. They broke up in 1976 amid various addictions and life changes, but not before releasing “Islands,” the final studio album to feature the original lineup. He and his wife, Maud Hudson, lost their home and belongings in the 1978 Agoura-Malibu fire. (Shangri-La is now owned by producer Rick Rubin.)

With the Band’s demise, Hudson settled into a consistent life as a session musician, appearing on records by Poco, Van Morrison, the Call, Camper Van Beethoven, Mary Gauthier and many others. Minus Robertson, the Band partially reformed in 1983 to tour, and spent the next three years as headliners and on bills with the Grateful Dead and Crosby, Stills and Nash. After Manuel’s 1986 suicide, the Band returned to the studio for 1993’s “Jericho,” but Robertson again didn’t join Hudson, Helm and Danko.

Hudson’s work on fellow Canadian Neko Case’s acclaimed ‘00s albums, “Fox Confessor Brings the Flood” and “Middle Cyclone,” reinforced the ways in which his oft-menacing organ chords and gorgeous improvised countermelodies have resonated across generations.

Garth Hudson in 2014.

(Rick Madonik / Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Approaching old age, Hudson and his wife returned to the Hudson River Valley. His life as a nonsongwriting band member meant that he didn’t own a percentage of any of the Band’s songs, and therefore didn’t receive regular publishing royalties from their work. By then, Hudson had long ago sold his share of the Band to Robertson.

In 2013, Hudson made the news when the owner of a New York storage space threatened to auction off his memorabilia due to nonpayment. Already saddled with at least three bankruptcies, he struggled to regain control of his archives.

Maud Hudson died in late February 2022. The couple did not have any children.

Along with his fellow bandmates, Hudson was inducted into Canada’s Juno Hall of Fame in 1989 and into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1994. In 2008, he and the Band were presented with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

Garth Hudson released two solo albums: the cassette-only “Music for Our Lady Queen of the Angels” in 1980 and “The Sea to the North” in 2001. Mixing styles, synthesizer and organ tones, a Vocoder voice box and a prog-rock album’s worth of tempo changes, on both releases Hudson composes and plays as though his muse can barely contain all the ideas flowing out.

This story originally appeared on LA Times