And then they began coming home … to no homes at all.

Eighty years ago, the Japanese and Japanese Americans — men, women, kids, two, three generations of families who had been locked up in wartime incarceration camps like Manzanar — were allowed to start leaving their confinement.

After the empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, fear went into overdrive. The West Coast felt much too exposed, and its Japanese population, native-born, naturalized, or immigrants, were automatically and groundlessly assumed to put Japan first in their loyalties, even spying or committing sabotage on its behalf. Better safe than sorry, right? And so, by Executive Order 9066, President Franklin Roosevelt authorized their removal and relocation to camps well inland.

In this photo provided by the National Archives, Japanese Americans, including American Legion members and Boy Scouts, participate in Memorial Day services at the Manzanar Relocation Center, an internment camp in Manzanar, Calif., on May 31, 1942.

(Francis Leroy Stewart / War Relocation Authority / National Archives via AP)

Throughout December 1941 and then into 1942, they’d been swept up by force from their homes and farms and jobs and sent away, most of them first to “assembly centers” like the Pomona fairgrounds and the Santa Anita racetrack, and then on to the camps. In all, some 120,000 were put behind barbed wire. Most of them had been living on the West Coast, and two-thirds of them were U.S. citizens.

Exactly who was “Japanese enough” to be rounded up and relocated? On paper, anyone who was 1/16th Japanese, which meant that if one of your 16 great-great grandparents was Japanese, you were too. It was another iteration of the American racist “one drop” rule, that one drop of Black blood made you Black. It’s a rule that enforced racial divisions and racist power on Black Americans for hundreds of years.

When they were swept up from their towns and neighborhoods and homes and workplaces in the weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese Americans had to abandon anything they couldn’t carry in a suitcase, which left them able to pack clothes, documents, toiletries, cooking instruments, and little else.

Newsletter

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there’s someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Homes, cars, shops and businesses, farming and fishing equipment, and of course land — it all had to be left behind.

It was chaotic, it was heartbreaking, and it was often an ugly thing to see. A rare few were fortunate to have non-Japanese friends who looked after their property for them, but for most, the rounding-up created a grasping free-for-all opportunity — for others. Goods were auctioned off for a fraction of their value, and owners sometimes took even the stingiest offers just to realize some cash. And sometimes, non-Japanese neighbors just walked in and took whatever they wished — and what were the Japanese going to do about it?

Afterward, Bradford Smith, who headed the Central Pacific division of the Office of War Information, called the removal “one of the greatest swindles in America’s boisterous history,” and suggested that the pressure to evacuate had started with those who had the most to gain from it.

On Terminal Island, where Japanese and Japanese Americans had settled and worked for decades at “Fish Harbor,” residents had 48 hours to pack and go. They had no leverage, no bargaining power, only a ticking clock, and, as Congress heard in testimony in 1942, they took what lowball offers were made: $25 for a $300 piano, hundreds of dollars’ worth of appliances for $25, fishing equipment abandoned and reportedly taken by canneries in the harbor. Even people’s pets were bought up, or perforce left behind.

In downtown L.A., the historic Nichiren Buddhist temple on East First Street, near the Los Angeles River, at first served as a warehouse for its parishioners’ property, but in June 1943, police and government officials showed up at the place and found … a mess, and nothing. The woman hired to take care of it all — who had power of attorney over the property — had flown the coop, neighbors said, along with truckloads of goods. What was left behind were a few boxes and trunks broken open, their scant contents scattered.

A year after the war ended, the War Relocation Authority, which set up and ran the camps, worked up a 112-page apology. Not exercising responsibility for safeguarding the property of the evacuees allowed “an interval of golden opportunity to swindlers and tricksters who had a terrified group of people at their mercy,” according to the apology. Almost 40 years in the future, a congressional commission would calculate the property losses, in 1983 dollars, at $1.3 billion, and a net income loss of $2.7 billion.

So eight decades ago, they came back, not only dispossessed of property but subjected to some of the same abuse they’d experienced when they were taken away. The Interior secretary, Harold Ickes, was a man who sometimes parted company with his own administration’s policy over what he wasn’t reluctant to call “concentration camps.”

In California, in the four months after detainees began leaving the camps, the War Relocation Authority report found two dozen incidents of intimidation or violence.

In rural California, at least 15 shooting attacks against Japanese Americans, an attempted dynamiting, three arson cases and five “threatening visits” amounted to “planned terrorism by hoodlums.” Some of those “bloodthirsty … race baiters,” Ickes believed, hoped to scare off the returning detainees from the “economic beachhead” they were trying to rebuild.

Evacuees move into the Manzanar internment camp on June 19, 1942.

(Associated Press)

In some quarters, opposition to them returning from the camps began well before the war drew to a close. In June 1943, a Los Angeles women’s auxiliary of the American Legion started petitions to keep any Japanese people from living on the Pacific coast again, claiming the “great danger” that even American citizens would pose “to carry on sabotage or other assistance to our enemy.”

About 5,000 displaced Southern Californians did find homes, of a sort, in two dedicated trailer camps in Burbank and Sun Valley. The Sun Valley camp was the longer-lasting, operating until 1956 as a community of about a hundred trailers, sharing community bathrooms and kitchens. The government sold or rented them out for $65 to $110 a month. Residents kept pretty much to themselves, rarely going far from the camp except in the protection of groups.

Residents called them “camps,” like the ones they’d left. When government officials came to check in, they kept correcting them: “ ‘This is not a camp. It is a trailer court,’ ” the officials insisted. Tomio Muranaga, who was a boy throughout the incarceration and postwar years, told The Times in 1986, “… They wanted us to forget about places like Manzanar and Heart Mountain,” the camps in California and Wyoming.

That the coming-home began eight decades ago had not occurred to me. Calvin Naito, an Angeleno and fourth-generation Japanese American, tipped me to the anniversary. He himself hadn’t known much about the incarcerations until he was studying at the Harvard Kennedy school in 1988, when President Reagan signed a historic law about reparations.

The road to that redress was long and trying, the earliest begun around 1948 under an evacuation repayment act.

Near Fresno, the Koda family had been major rice growers who owned 5,000 acres and leased another 4,000 in December 1941, before they were hustled off to the camps.

Their claim against the federal government took about 15 years, and by 1965, when the settlement check arrived, the elder Kodas had died. Ed Koda, one of the sons, calculated then that what the government offered, $362,500, represented about 15 cents on the dollar for their $2.4-million claim. The fourth-generation Kodas still farm rice today, in Yolo County.

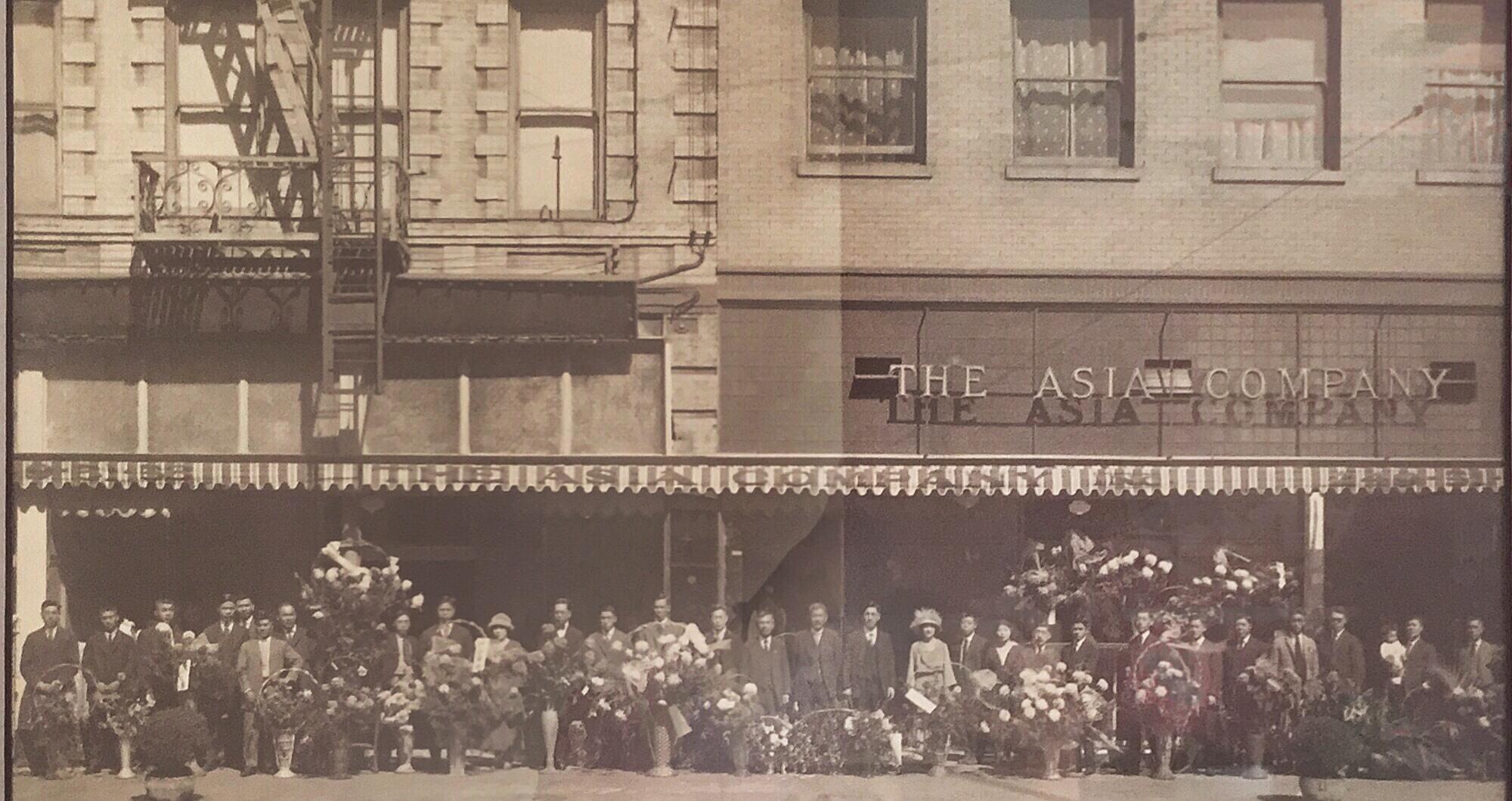

The Morey family too has done business for four generations in California. In 1907, Joshua Morey’s immigrant great-grandfather began the Asia Co. import-export business in Little Tokyo, and the family lived in a house in South L.A., near Manual Arts High School.

The Asia Co. was an import-export business that operated in Los Angeles. It was started by members of the Morey family before they were interned.

(Joshua Morey)

Their story was repeated by the thousands. Business and home left behind after the Pearl Harbor attack, the family left with what fit into two suitcases.

Morey’s great-grandfather, who came here in 1892, was sent to a detention camp in Tuna Canyon where the feds kept the foreign-born it regarded as security risks. Morey has read the FBI reports, and thinks he knows why his great-grandfather was sent there, while the rest of the family went to lower-security camps. “The Asia Co. was one of the businesses in our community prewar, and because he did so much business with Japan, I think he was lumped in, like maybe he was one of the spies.”

A Los Angeles Times advertisement on June 14, 1942, promotes an auction of the fixtures and products sold at the Asia Co. after the Morey family was sent to internment camps during World War II.

(Los Angeles Times)

“We had owned land in Little Tokyo, on First Street, where the business was. We lost the property, lost the business, came back to nothing.”

Restarting an import-export business with Japan was out of the question in the postwar U.S. But paradoxically, Morey’s grandfather, with his expertise in distribution systems for the Asia Co., was hired by the U.S. Army and sent to postwar Germany to manage the movements of military goods there.

Back in the U.S., the family found its new niche in insurance. “Post-World War II, no insurance company would insure Japanese people or their properties. That’s an example of how we were treated after the war,” Morey said.

The need and the opportunity matched up, and Morey’s insurance company still insures Japanese communities in California and Hawaii.

His family moved to the Bay Area when Morey was 3. In the 1980s, Norman Mineta, a survivor of the Heart Mountain incarceration camp, was settling into his job as a member of Congress. And the Moreys bought Mineta’s insurance business. “I grew up with Uncle Norm. He told people that he changed my diapers, and I said, Uncle Norm — I was 3 years old!”

You may know that name, Norm Mineta. San Jose’s international airport is named for him. He’s also a linchpin to what happened to compensate once-imprisoned Japanese Americans. Morey’s father, a bit reluctantly, would talk to his son and tell him, “Your Uncle Norm is trying to push to make what happened right.”

Lori Matsumura visits the cemetery at the Manzanar National Historic Site near Independence, Calif., in 2020.

(Brian Melley / Associated Press)

Mineta and other Japanese American members of Congress nudged and negotiated and legislated for years to “make what happened right.”

One of Mineta’s colleagues in this was the Hawaii senator Daniel Inouye, who lost his right arm fighting with a celebrated all-Nisei combat team in the U.S. Army in Italy in World War II. (Inouye’s arm was shot off as he tried to toss a grenade into a German machine gun nest. Inouye used his left hand to pry the grenade out of his severed right hand and tossed the grenade into the German bunker.)

In brief: The matter slogged forward from the first postwar compensation program that paid the Koda family about 15 cents on the dollar, into the early 1980s, when a congressionally established inquiry took testimony and made recommendations for redress. Finally, in 1988, Reagan signed the Civil Rights Act of 1988, an apology for the injustices of the detention, and cash amends of $20,000 to each living Japanese American citizen or legal resident who’d been imprisoned, then numbering about 80,000.

The ranks of the living who came back from the camps are thinned now, and eventually, of course, will be none. Joshua Morey knows their stories only secondhand, but now, “it’s become my life’s mission, our Japanese American story in America.”

“Our story is important to our community but also to America. Many communities’ stories are so different, but have this common thread of this is what America is. Whether it’s good or bad, struggle and success, it can’t be forgotten.”

This story originally appeared on LA Times