To celebrate 2025, I compiled Apple’s top ten major areas of innovation over the past 25 years. Let’s look at the decisions that led to this blockbuster success of the iPod and implications for new products today.

The first segment discussed Apple’s 2000 release of Mac OS X Public Beta, its most important innovation in the last 25 years. The second segment focused on Apple’s reinvented retail operations. The third segment looks at iPod.

Apple cheats death with a strategy of innovation

If the “Apple Computer” of the new millennium had only focused on retrofitting the Macintosh to sell as its principal money maker, it is unlikely it would have survived a decade. At the time, Apple was selling about 3 million Macs annually. Apple was beleaguered.

Apple was also innovating. It had launched a series of well received Mac products, from the original 1997 iMac G3, to the 1998 iBook, the 1999 “supercomputer” Power Mac G4 and the titanium PowerBook G4 in early 2001. Cautious optimism was beginning to sprout about the company’s turn around under the initial years of Steve Jobs‘ charismatic and pragmatic reinvention of the company.

Concerns arose from dark clouds during the Dot Com boom. Apple’s PowerMac G4 Cube, released just as the market peaked, faced tepid sales. The stock market crash further impacted demand, but the fancy by pricey Cube wasn’t a compelling choice for many core customers in creative markets or education. Apple misjudged its potential audience right before its buyers were increasingly forced to retreat away from luxury purchases.

It appeared there was an inherently limited potential audience for Macs, and that was a problem for Apple. Increasing competition from cheap commodity PCs further eroded sales prospects for high-end desktop and laptop computers. Apple really needed something to goose its sales.

To boost Mac demand among professionals, Jobs’ Apple focused on producing exclusive new software titles. Apple acquired Final Cut from Macromedia in 1998 and relaunched it as Final Cut Pro in 1999. Three years later, it acquired Logic from Emagic. One of Apple’s greatest innovations was to leverage great software to help sell its hardware.

At the same time, Apple embarked upon a similar strategy for home and education users, launching iMovie in 1999 as an easy to use movie editor alongside the New iMac DV. That same year, Apple bought SoundJam MP from developer Casady & Greene, with the intent to turn the music library software into iTunes.

Apple pursued an innovative strategy of launching creative, easy to use new first party apps to drive interest in its Mac hardware. This created a “digital hub” for users, where the Mac transformed from being just a browser and email machine into a creative center for a user’s increasingly connected “digital life” of movies, photos and music.

Apple wasn’t making tremendous revenues from selling its software. These new titles existed primarily to drive Mac adoption. But having its own bundled software opened up new opportunities for the company, with the first clearly being its new accessory for iTunes that acted as a remote “pod” for taking desktop music anywhere.

Apple didn’t invent portable music. While the company did pioneer key elements of desktop editing of digital audio and even digital video a decade earlier with QuickTime in the early 90s, its reliance on third party developers to actually make use of its QuickTime middleware to deliver powerful Mac apps began to falter with the release of Microsoft’s Windows 95.

The creative tools industry, including Adobe and Macromedia, began to focus on volume PC customers with Windows versions of their products. Microsoft was also doing all it could to scuttle Apple’s QuickTime. It pushed its partners to stop using and distributing Apple’s software in favor of its own. Microsoft even stole code from Apple’s QuickTime to improve the performance of its own media software for Windows.

On the music front in particular, Microsoft also began to pursue a strategy of tying all commercial music to its own proprietary players via its Digital Rights Management security software. It wouldn’t matter how attractive Apple’s music hardware and software were if its much more powerful PC competitor controlled the spigot of all licensed music and could turn this off for Mac users on a whim.

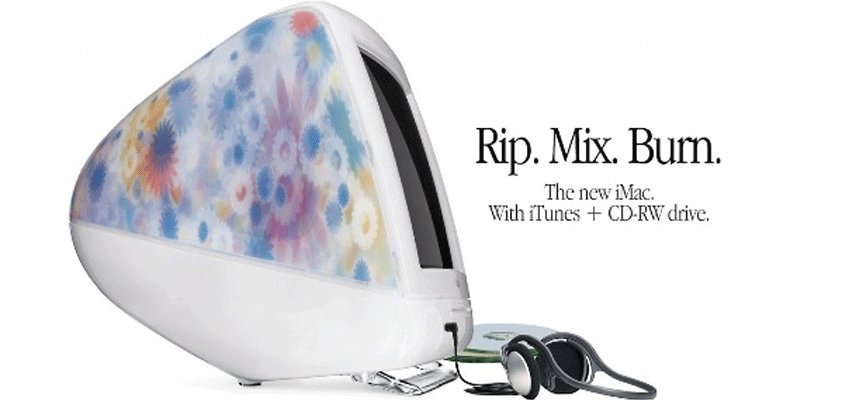

Apple’s iTunes strategy recognized this threat. It attempted to create an alternative to Microsoft’s Windows Media and Sony’s parallel efforts to lock up commercial music with its own DRM. In 2001, iTunes launched with the advertising campaign “Rip. Mix. Burn,” alongside a new iMac with Apple’s first CD-RW optical drive.

Apple wasn’t first to install rewritable disc recorders in a PC, but the combination of iTunes’ ease of use within the overall Mac package resonated with users. Part of Apple’s strategy of innovation was simply recognizing what people wanted to do, and doing the work to make that easier.

By freeing users to ingest their existing CD libraries and burn selected playlists onto standard CDs they could use anywhere, an iMac running iTunes offered a vastly better experience than the complex and restrictive rule sets Microsoft and Sony were attempting to push on users.

Microsoft was catering to its music partners, offering them broad flexibility with Windows Media to limit how users could use their own songs. Sony was largely working to link media sales to its own hardware, notably its new MiniDisc portable format that encouraged users to buy another new media format. It even limited what users could put on their own MDs.

Apple was selling a superior experience directly to its customers. Its entire strategy was designed explicitly for its customers, not for its partners. Many recording labels were initially hostile to the concept of users making copies of their own music, even though music piracy had already become well established. While Microsoft and Sony were trying to put that cat back into the bag, Apple was offering an entirely new way to think about music— initially to sell Macs, then to sell its own music player.

MP3 players had already become popular devices by the late 90s, but they had a few significant shortcomings. In order to store more than just a few songs, they either had to use rewritable optical media or a conventional hard drive, both of which were bulky and fragile.

Navigating the music on such a device quickly became unwieldy as song libraries expanded. The connectivity between players and a PC capable of copying song files to the portable device was also problematically slow. Battery life was an issue. Solid state storage was still too expensive to use liberally.

Apple fortunately had a variety of solutions already. Its work with digital video had resulted in Macs getting fast Firewire ports starting in 1999. The new iTunes offered a way to organize and sort files on a powerful computer, and to apply metadata to help navigate large libraries on an external device.

Toshiba had developed a compact hard drive it was shopping around to buyers without finding much interest. Seeking to enter the music player business, Apple launched a team under Tony Fadell to turn the concept into an attractive product.

Apple’s limited experience in consumer products outside of Macs meant that much of the iPod’s details were contracted to others. PortalPlayer software and a UI system by Pixo helped Apple focus its internal work on the hardware experience and its integration with iTunes. The result was a luxurious 5MB portable system with fast FireWire connectivity. Bulky HD and optical players suddenly looked really old fashioned, and their serial or USB 1.1 speeds felt anemic in comparison.

Apple also benefitted from its prior decade of experience with laptops and batteries, but it still had to develop significant elements of iPod’s portable hardware from scratch, or rely on third party chips and other components. The real product Apple was selling was the iPod experience.

Today, Apple has the size and resources to custom develop its own software from apps to the OS to the underlying firmware. It designs its own hardware right down to the silicon in many cases. But what Apple continues to sell is still an overall experience.

The revolution of a portable Apple

Initial sales of iPods were, by today’s standards, relatively limited. In 2002, its first fiscal year of iPods, Apple had sold fewer than 400,000 units. In 2003 it sold nearly a million. But in 2004 that figure jumped to 4.4 million, followed by more than 22 million in 2005 and almost 40 million in 2006.

The exploding growth and expansion of the iPod family of devices radically shifted Apple from being a fringe computer maker to being a very high volume device manufacturer. Apple was not only selling incredible volumes of devices, but also buying up vast strategic reserves of components such as RAM and hard drives.

Apple’s high volume purchases for iPod also helped improved its negotiating power for Mac components. It also took lessons learned from iPod to its Mac models. Experience with iPod also helped to commodify components of the Mac.

While FireWire was initially much faster than USB 1.1, Apple quickly incorporated early support for USB 2.0 to help sell iPods to Windows users. It also ported iTunes to PCs, giving many Windows users their initial introduction to the Apple world.

iPod also played a key role in the company’s newly built Apple Stores. It brought in an entirely new group of users and introduced them to the Mac. It also helped establish the Apple Store as a showplace for regular new introductions of iPod models.

High volume iPod sales also helped Apple partner with third party accessory makers. Apple’s own clumsy attempts to deliver accessories, ranging from iPod Socks to iPod HiFi, made it essential for the company to work with smaller developers who could try out a range of options to fit users needs.

Did it have to be iPod?

In retrospect, Apple’s monumental success with iPod and all of its surrounding innovations, the halo it cast over the Mac, and the foundation it helped lay for Apple’s forthcoming portable and wearable products, all seem as if they could have been applied anywhere.

Why did Apple pick portable music as its focus, rather than say, digital photography? Was iPod just the success Apple created from of a random strategic choice and just a lot of clever marketing? Could the same amount of effort just as well have been invested into an “iCam” with the same results?

The Apple of the 1990s had actually already pursued multiple experiments in portable devices categories. It most famously began work on a “digital assistant” that became the Newton MessagePad in 1994.

Apple spent tremendous funds developing custom OS software, a unique programming environment, innovative stylus-based apps and services, and even bespoke ARM chips suited to the mobile device.

Rather than being a smash success, Newton actually suffered from being excessively ambitious— it wasn’t quite finished at launch and cost too much to be broadly attractive for what it could do.

It’s less well known that Apple also pioneered digital photography, working with Kodak to deliver QuickTake cameras starting in 1994. Like iPod later would, this product also leveraged Apple’s multimedia software to manage and organize its digital files. Unlike iPod, Apple’s QuickTake cameras arrived without the showcasing power of its forthcoming Apple Stores.

Like Newton, QuickTake cameras were quite expensive and limited in what they could actually accomplish. Also like Newton, the QuickTake line was quickly discontinued by Jobs after his return to Apple in order to simplify operations.

What prevented Apple from returning to digital cameras in 2001, rather than shifting its mobile focus to digital music with iPod?

In part, digital cameras offered Apple a lot less commercial opportunity. By 2001, digital imaging technology had improved significantly, but most of the value in the industry was being captured by high end camera makers selling professional digital cameras priced closer to $8,000.

Pro photography users could afford to benefit from the advantages of shooting digitally, but they represented a much smaller market with limited potential for growth.

Consumer digital cameras priced around the $800 range of QuickTake offered limited advantages over more affordable, standard film cameras. Quality at that price point was still struggling to catch up to film, while film photos could already be digitized after they were developed, even put on a Photo CD for use with computers.

Apple’s digital camera competitors were also a lot better established and competent than makers of MP3 players. Apple had less to offer in terms of improving upon the experience of cameras compared to what it could do to make a better MP3 player.

Among camera makers, there were lots of very competent, highly competitive manufacturers already well versed in advanced optics and increasingly sophisticated custom chips and digital sensors, and were adept in delivering general usability. These makers were also already making money from their film cameras.

MP3 manufacturing was scattered across smaller players making bulky optical or hard drive players, or very limited Flash Memory devices. USB had arrived but was still slow. It would be easy to liken the MP3 market in 2001 to where mobile phones were in 2007, or smart watches in 2014, or VR headsets in 2024.

iPod’s music supply

Another strategic element essential to iPod was missing in the market for digital photography. While end users could create their own music just as they would take their own photos, most music listeners would be trying to listen to commercially recorded music.

Digital cameras weren’t similarly offering to play TV and movies or offering users a library of stock photography to view. In fact, a major reason why Apple pursued iPod was the parallel potential offered by what would become the iTunes Music Store. There was no analog for digital cameras.

Today we may think of the iTunes Music Store as a major new profit center for Apple, but its original impetus wasn’t making lots of money. Instead, much of Apple’s strategy for iTunes was simply aimed at making a parallel source for commercial content for Macs and iPods.

Apple was focused on selling hardware and earning the majority of its profits from Macs and later iPods. It frequently acknowledged, initially, that it was running iTunes Music Store at break-even.

Around 2000, the digital music industry was being held back by Microsoft and Sony’s rival efforts to push their own DRM. If Microsoft and Sony had succeeded in locking up commercially recorded music with their DRM, the market for all of Apple’s hardware would have been imperiled.

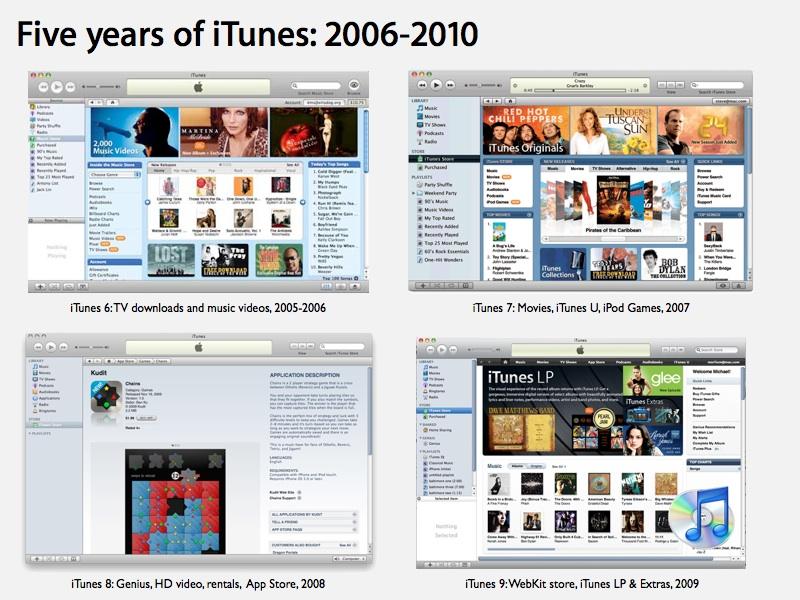

There is limited appreciation of Apple’s expertly delicate dance over the 2000s— first embracing ripped CDs, then transitioning to single track music sales in the iTunes Music Store, and then introducing FairPlay DRM to appease music labels without turning off its customers.

The development of iTunes in parallel with iPod required an entirely new way of thinking about digital content that is remarkable enough to deserve its own top ten article.

iPod legacy

Before looking at the iTunes Store, consider the lasting legacy of Apple’s investment and innovation in its digital music hardware.

Apple’s initial, incremental sales of iPods helped the product to rapidly improve. Between 2001-2003, consumer demand for more storage took the original 5GB iPod to 10GB and then 20GB models, facilitated by the shrinking sizes and increasing densities of hard drives.

Apple didn’t develop these hard drive mechanisms. Instead it relied on a series of competitive suppliers all seeking to deliver better components to win Apple’s high volume business. Today, Apple similarly doesn’t create all of its own components. It relies on Sony and Samsung for cameras and displays, and uses storage and RAM developed by others.

While Jobs was credited with the vision of what iPod should look like and how it should feel, it was Apple’s operations executive Tim Cook that brokered the company’s exclusive component deals, giving it competitive advantages over other companies seeking to enter the music player market.

If Apple had tried to build everything on its own, it would end up heavily invested in high risk industries like memory and sensors just like Sony and Samsung, and reliant on others to help it sell what it had developed.

Instead, Apple has selected certain strategic areas where it can beat the rest of the industry— such as today’s Apple Silicon— while relying on many commodity parts advanced by others. Much of the innovation was driven by gathering the understanding of where it could add value, and where it could lean on partners.

Apple not only negotiated massive supplier deals for iPods, but also expanded sales of iPods with key partners. In 2004, the significantly larger HP began licensing Apple’s iPod instead of developing its own product.

That same year, Microsoft rushed out its own Windows Portable Media Center and began licensing its designs for Portable Media Players with Samsung, Creative, iRiver and other PC and device makers.

Microsoft’s failure to beat Apple’s iPod with its “Windows” branded alternatives cast the first serious doubts over Microsoft’s supremacy in the tech world. The company sealed that fate with the Zune, introduced in 2006, even before Apple’s iPhone obliterated Microsoft’s other mobile efforts. This dramatically shifted views on Macs as well.

Apple didn’t just sit back and rake in iPod profits. Instead, it relentlessly innovated in creating new tiers of iPods. In 2004 Apple launched iPod mini using an even smaller, thinner hard drive. It was offered it multiple colors as a more affordable option. Its high volume sales continued to keep Apple a competitive component buyer and honed its design capabilities.

Apple’s increasingly precise and exacting design and manufacturing capacity greatly improved the Mac as well, helping to transform the iMac into a tightly integrated package behind an LCD. This also helped Apple to increasingly improve upon the size and durability of MacBooks and their batteries and storage.

In 2005 Apple introduced iPod nano using Flash Memory instead of a hard drive. The company preferred to rapidly cannibalize its own product lineup to stay competitive and innovative. The nano accelerated the mini’s focus on fashion and helped Apple shift away from tech specs into being an aspirational brand.

Apple’s mass consumption of Flash Storage for years of iPod nano helped prepare the company to pioneer the use of SSD storage in the forthcoming MacBook Air in 2008.

Alongside iPod nano in 2005, Apple introduced iPod Shuffle, an ultra-portable version with no screen, emphasizing simplicity and affordability. Its smaller size and random music playback focused on a new role in running and workouts.

Parallel with these two new smaller directions for iPod, 2005’s iPod Video shifted the high end iPod into being a more sophisticated multimedia device for presenting TV shows, movies and music videos. That functionality expanded Apple’s media leverage beyond music and acted as a shoulder for iPhone to stand on at its launch two years later.

Not only did iPod blossom into iPhones, but the wrist-wearable 6th generation iPod nano effectively inspired the later development of Apple Watch, completely shifting the company from being a device maker to being a lifestyle brand selling luxury wearables.

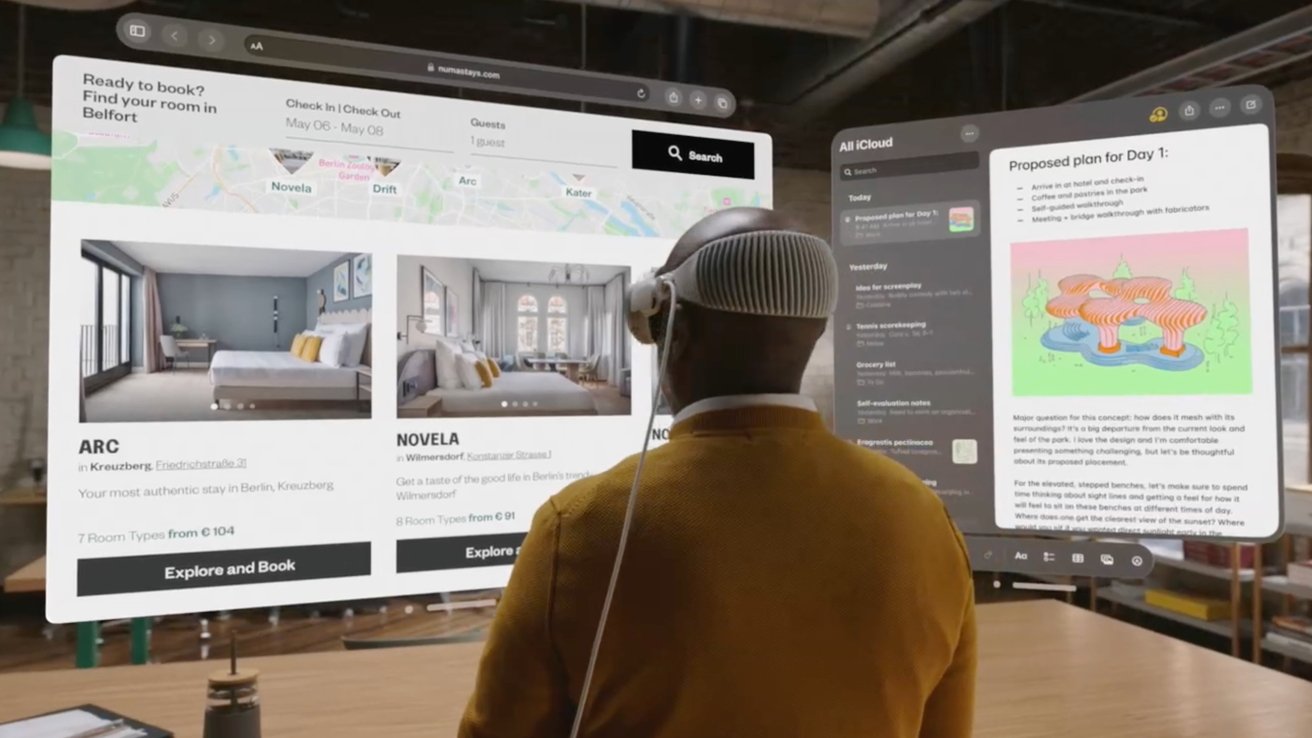

You could even make the case that iPod played a role in defining today’s Vision Pro. Unlike many others in the AR/VR space, Vision Pro was created as a standalone, self contained device that can sync with your other devices as a peer, rather than being tethered from them as a mere peripheral.

iPod defined the decade of the 2000s. It shaped the development of Apple’s global supply chains for consumer devices, and helped revolutionize how we use digital media. It survives, not as hardware, but as software functionality. Its hardware wasn’t even officially discontinued until 2022.

iPod wasn’t one single innovation or invention but rather a continuation of strategic developments that successfully pursued increasing areas of utility, multiple price points, and radically shifting form factors.

Imagine if the world had paid attention to early critics pouting about missing features or had cared that early sales took some time to really shift the computing landscape and change everything!

That provides some perspective for Vision Pro today, at a time when Apple has far more market power and the ability to develop its own custom silicon and even produce its own bespoke immersive content. Vision Pro is, effectively, an iPod for your eyes.

This story originally appeared on Appleinsider