Nearly nine months after the Eaton fire destroyed something unique, something beloved, something cherished even more in death, the mountains remain scarred and dusty streets criss-cross the vanished neighborhoods of what is still, essentially, a ghost town.

If it’s true that time heals all wounds, the clock is moving slowly in Altadena, where 9,400 structures were destroyed and 19 lives were lost.

There will be a resurrection, without question. Building permits are grinding slowly through the bureaucracy, hammers are swinging and a new Altadena will one day rise from the ashes.

I know one homeowner who hopes to be in his newly built house in a month or two. Victoria Knapp of the Altadena Town Council told me she knows people who sold their lots immediately after the fire and now regret it. And L.A. County Supervisor Kathryn Barger said the permitting process has been revamped and she doesn’t sense that many people are bailing on Altadena.

But as we head for Halloween and Thanksgiving and round the corner of one year into the next, roughly two-thirds of property owners have not yet applied for building permits, and there is widespread frustration, exhaustion and uncertainty.

People who were fully committed to rebuilding in the immediate aftermath of destruction are now rethinking it, having grown weary of the slog.

“It could be years of living in a construction zone, and that’s had me awake in the middle of the night with some panic attacks,” said Kelly Etter, who lost the house where she lived with her husband and ran a Pilates studio.

“When I go up there every week,” said Elisa Nixon, whose home was badly smoke-damaged and needs an interior gutting, “I find it really sad and really depressing. I’m trying to imagine myself living there, and it’s really hard.”

Taylor Feltner, who lived with his wife in a smoke-damaged Pasadena home on the edge of Altadena, would like to stay in the area because his wife’s Altadena family is a big part of their lives. But they’re no longer sure what to do or how to decide.

“We have wavered so much throughout this whole process, because every time we have a fight with the insurance company it’s like reliving the trauma of that night over and over again,” Feltner said.

An aerial view of cleared properties and a home under construction this month in Altadena.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

He and his wife are in their eighth temporary home since the fire. His mother-in-law, whose Altadena home survived the fire, wears a mask when gardening in the backyard. Feltner said he and his wife planted fruit trees in their own yard, but wonder if it’ll be safe to eat the fruit when they go back home, given widespread contamination and haphazard testing.

“Everything feels broken apart now,” Feltner said.

I get it, and I honestly don’t know if I’d be able to endure what people from the Altadena and Palisades areas are going through. I get impatient if a problem isn’t resolved in a day. The fire survivors are in limbo, still, with no idea how many years of upheaval they’re in for.

Joy Chen, co-founder of the Eaton Fire Survivors Network, has been tracking community sentiment for months. She said an initial, “almost defiant” sense of pride, with T-shirts and property signs declaring “Altadena is not for sale,” still lingers. But “a dose of reality” has set in.

Here’s what people are sorting through, said Chen:

How long will it take to get back home? Can we afford to rebuild? Will our kids be safe, given lingering contamination? Is the Southern California Edison settlement proposal a fair deal or a ploy to avoid bigger payouts? Will the new Altadena remotely resemble the place we loved? And will we ever sleep well in an area that has not seen the last of wildfires and frightful winds?

Even for those who can see their way past all of that, said Chen, there’s a gap between their insurance settlement and the cost of rebuilding.

“It’s around $300,000 on average,” said Chen, “and that’s a huge hurdle.”

Barger said the settlement proposal from Edison could help close that gap for some people. But the investigation into the fire’s cause is not yet complete, and some lawyers have advised clients not to accept what they consider a lowball offer. And yet, for those who pass up on the offer, it could take years for lawsuits to play out in court.

Chen, a former deputy L.A. mayor, has been demanding that insurance companies deliver what their clients paid for, and imploring state insurance commissioner Ricardo Lara to get tough with them. According to the nonprofit Department of Angels, 70% of the roughly 2,000 insured Eaton and Palisades fire survivors who were surveyed said delays, denials and underpayments are “actively derailing recovery.”

“These delays and denials aren’t just devastating to families, they’re illegal under California law,” said Chen. “It’s Commissioner Lara’s job to stop them. His refusal to act is stalling the entire Los Angeles recovery. Families who spent decades building stability for their kids are watching those futures slip away.”

Lawsuits are pending against multiple insurance companies, including Feltner’s carrier: Mercury.

“They’re fighting us on everything,” said Feltner, who has filed complaints with what he called the “toothless” state insurance commission.

For one Altadena family, whose house survived with minimal damage, it wasn’t an insurance issue that exhausted their resolve. Initially committed to moving back in, they later sold their house and relocated to another area. They asked me to withhold their names for privacy reasons.

“It boiled down to risk,” said the husband, citing concerns about contamination, years of construction noise and dust, and the impossibility of knowing if the new Altadena will resemble the one that drew them there in the first place.

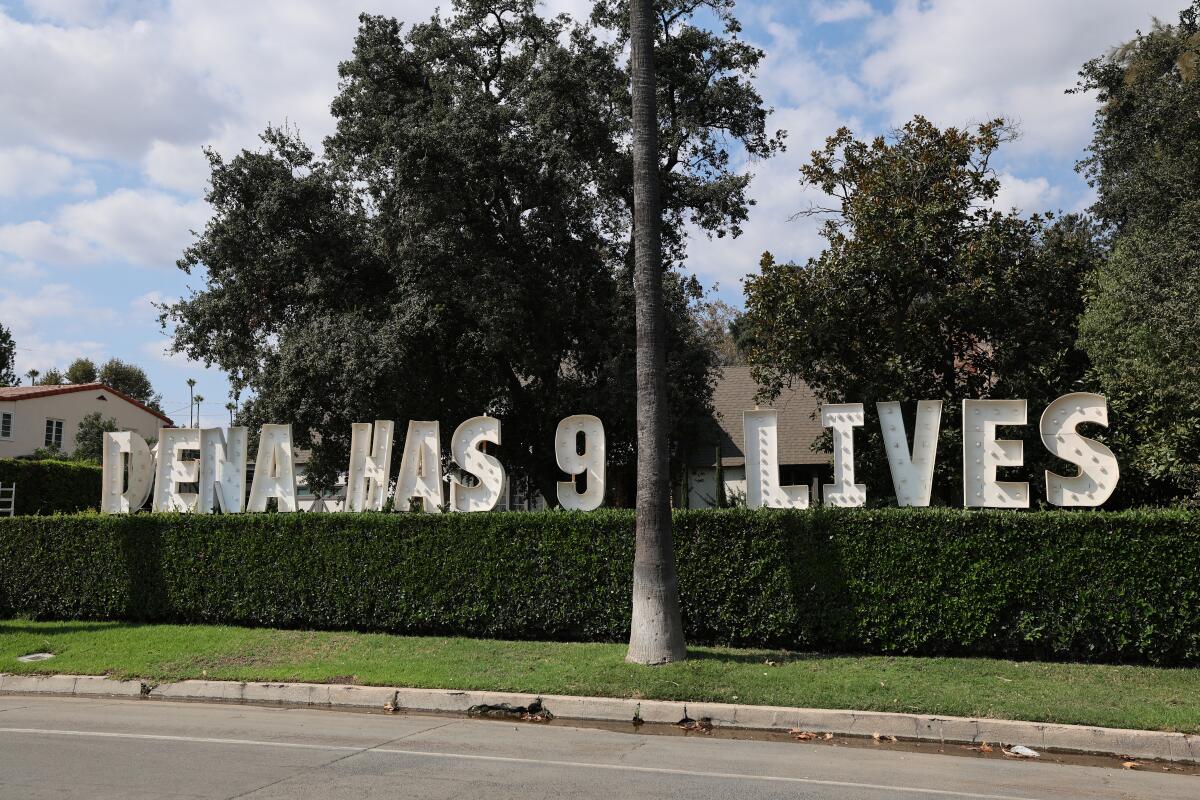

A sign adorns a homeowner’s Altadena property.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

“It was a head decision and not a heart decision,” said his wife, who still feels attached to her home, her street, and to Altadena. “I don’t think that will go away. Obviously, this trauma is a part of us now, but our heart and our memories will always be there.”

Tim Kawahara, executive director of the UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate, grew up in Altadena and his mother still lives there in a house that survived the fire. The rebuilding of Altadena is in the early stages, he said. With thousands of separate projects to push through the permitting process, and a construction workforce shortage compounded by immigration raids, the new Altadena is not yet on the horizon.

“You’re talking about three years to start seeing some considerable building happening, and probably more like five years for something happening at some big level. But it could take up to 10 years,” Kawahara said. “And it’s not just homes. It’s schools, parks, libraries, police stations and infrastructure, too.”

You could argue that there’s something exciting about the chance to draw a new community on the blank canvas of the old one. But that’s a lot to endure if you’re breathing the dust, and as speculators move in and properties turn over, who’s going to be in charge, what will homeowner insurance cost, and will character and history survive?

“People are suffering and struggling to find their way, and they don’t trust anyone anymore,” said Nixon. “And with all of that comes this feeling of, this is too much. It’s hijacked my life, I can tell you that. It’s overwhelming, the amount of work it takes to stay on top of this and also just keep your life balance.”

“Having so many unknowns is just incredibly exhausting and limits capacity for enjoying other areas of life,” said Etter. “The connection to community, to neighbors and fellow survivors has really been a lifeline. There’s shared resources, hugs, and midnight texts in the middle of the night when you’re panicked about whatever.”

In coming weeks, I’ll be exploring different angles of the Eaton fire recovery story, so feel free to share your thoughts with me.

What can be done to speed the process?

What should Gov. Gavin Newsom and legislators do to speed fair resolution of insurance disputes?

Given climate change and the fire-prone natural geography, would you consider a move to Altadena?

What will Altadena look like in five years, in 10, in 20?

Who should decide?

Who will decide?

steve.lopez@latimes.com

This story originally appeared on LA Times