The genesis of the most pivotal year in hip-hop began in the summer of 1987. Hank Shocklee was listening to his car radio on the way to a Long Island movie theater with his family when Eric B. & Rakim’s “I Know You Got Soul” suddenly jumped out of the speakers. By then, the iconic duo’s platinum debut, “Paid in Full,” had seemingly changed the direction of rap overnight.

Shocklee, a founding member of Public Enemy’s innovative production team, the Bomb Squad, sat gobsmacked. He frantically called PE’s lead orator, Chuck D, who was also overwhelmed by what he had just heard.

“‘I Know You Got Soul’ stopped time,” Shocklee recalls. “When that record came out, every other song was quiet. Me and Chuck got mad because ‘I Know You Got Soul’ was too good [laughs]. Now we had to do something to top that.”

That was easier said than done. By then, Rakim had already rewritten the rules of emceeing, eschewing rap’s slower, linear B-boy rhymes for faster, more complex patterns and deeper lyricism: “I start to think and then I sink into the paper like I was ink / When I’m writing, I’m trapped in between the lines / I escape when I finish the rhyme…” James Brown was now hip-hop’s go-to sample king, a cheat code that endowed Eric Barrier (Eric B) and William Griffin Jr. (Rakim) with unmitigated raw funk.

In July 1987, Public Enemy unleashed its answer: “Rebel Without a Pause.” The revolutionary track would become the anchor to the group’s political rap masterpiece, 1988’s “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back,” often hailed as the greatest hip-hop album ever recorded. What started as Shocklee and Chuck D attempting to one-up their friends and fellow Long Islanders foreshadowed something much more profound: hip-hop’s rebellious transformation.

Since 1984, Run-D.M.C. had set the bar for rap greatness, a swaggering testament to hip-hop’s redemptive, started-from-the-bottom triumph. But by ’88, the genre had become Blacker, more socially and politically conscious and, at times, more confrontational.

“That was the year that defined the culture,” says Shocklee. “Hip-hop mirrored the plight of Black people. There was a fight to gain acceptance into the mainstream community because we were making records that were amazing and selling millions but couldn’t win any awards. Hip-hop was called noise. That rebelliousness that you hear in ‘88 is coming from a generation of kids that weren’t being heard.”

And “Rebel Without a Pause” was ground zero. “Brothers and sisters, I don’t know what this world is coming to!” the Rev. Jesse Jackson declared on the track’s dramatic opening, lifted from the 1973 “Wattstax” documentary soundtrack. Chuck D’s booming voice resonated like a fire-and-brimstone street-corner preacher fighting for his people to be free.

With irreverent, clock-wearing sidekick Flavor Flav by his side and DJ Terminator X, Professor Griff and the S1W’s posse as intimidating backup, Chuck shouted out the Black Panther Party and controversial radical fugitive Joanne Chesimard, a.k.a. Assata Shakur. He dissed “radio suckers” that refused to play the group’s music and gave the middle finger to Ronald Reagan (“Impeach the president, pulling out my ray gun / Zap the next one, I could be your Shogun!”).

“It Takes a Nation…” made PE’s first album, “Yo! Bum Rush the Show,” sound antiquated. Meanwhile, on the West Coast, another album raised the temperature not just of popular music but also of the city of Los Angeles: N.W.A’s incendiary August 1988 debut, “Straight Outta Compton.”

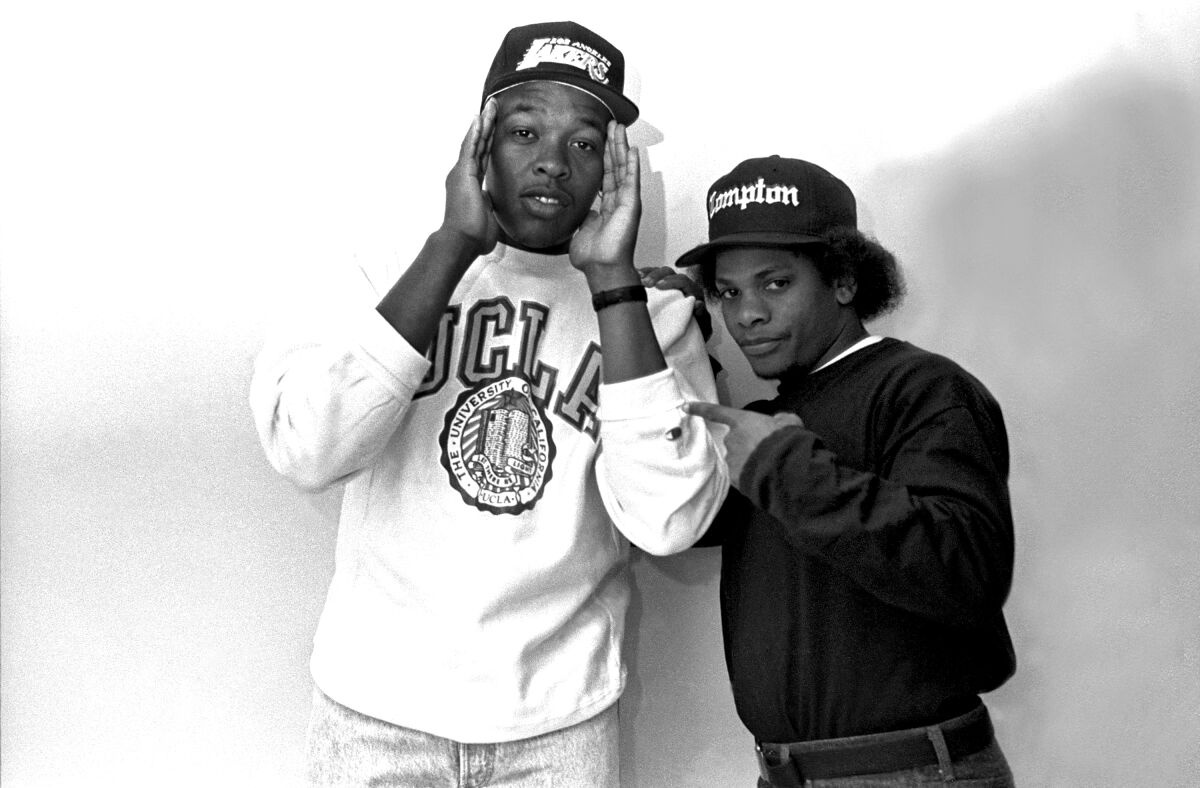

Former drug dealer Eric Wright, a.k.a. Eazy-E, had no interest in saving the world. The Compton native, who left his dangerous street occupation, established the label Ruthless Records and hooked up with local emcees Ice Cube and MC Ren, producer Dr. Dre and DJ Yella. They called themselves N— with Attitude.

N.W.A’s Dr. Dre and Eazy-E.

(Al Pereira / Getty Images)

“Straight Outta Compton” was a Molotov cocktail thrown at white America’s Moral Majority. “A young n— got it bad ‘cause I’m brown / And not the other color, so police think they have the authority to kill a minority,” Cube declared on the infamous anthem “F— tha Police.”

It was the message in the music that made hip-hop in ’88 truly transcendent, and Public Enemy and N.W.A. were not alone in pushing rap to new heights.

Boogie Down Productions visionary KRS-One appeared on the cover of the Bronx crew’s second release, “By All Means Necessary,” referencing the iconic 1964 photo of Malcolm X peering out his window while holding an M1 carbine rifle. Not to be outdone, former South Central street hustler and Crip member Ice-T — whose 1986 single “6 in the Mornin’” is credited with birthing gangsta rap, earning him hip-hop’s first warning sticker — continued to stoke the ire of watchdog organizations like the Parents Music Resource Center.

Both the infamous cover of Ice’s ‘88 opus “Power” (his scantily clad then-girlfriend, Darlene Ortiz, was photographed holding a pistol grip shotgun) and the LP’s explicit lyrics drew outrage over what some politicians, parental groups and media outlets viewed as the rapper’s brazen glorification of sex and violence. Ice flipped the script on his critics with the album’s first single, “I’m Your Pusher,” taking on the role of a drug dealer who instead of selling dope pushes dope hip-hop.

Rakim further expanded the lyrical possibilities of rap on “Follow the Leader,” his second collaboration with Eric B, peppering his dense rhymes with lessons from the Nation of Islam offshoot Five-Percent Nation. Suddenly, it wasn’t enough to just be braggadocious on the mic. “Kicking Knowledge” was now part of hip-hop’s cultural lexicon.

Meanwhile, Salt-N-Pepa was waving the flag for Black women’s empowerment on the radio hit “Shake Your Thang (It’s Your Thang),” cutting through the misogynistic noise with one declarative line: “Don’t try and tell me how to party / It’s my dance, yup, and it’s my body…”

And the Jungle Brothers’ Afrika Baby Bam, Mike Gee, and DJ Sammy B signaled the arrival of the Native Tongues crew, consisting of thoughtful, like-minded New York free spirits like A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, Monie Love and Queen Latifah. Their revelatory debut, “Straight Out the Jungle,” exemplified hip-hop’s embrace of Afrocentrism. Even the members of the mighty Run-D.M.C. took off their gold chains and replaced them with Africa medallions.

Hip-hop was changing from within, driven by societal forces that hit the Black community particularly hard. New York City was boiling over from a volatile mix of racially motivated incidents, double-digit Black unemployment and a cheap, highly addictive drug that swept through America like wildfire, especially in Harlem and the Bronx.

In ’88, the crack cocaine epidemic was on the minds of rappers as everyone from Public Enemy (“Night of the Living Baseheads”) to a 16-year-old MC Lyte (“I Cram to Understand U (Sam)”) addressed the devastating damage the drug was inflicting on the Black community.

On the West Coast, Los Angeles was making national headlines for tumultuous gang violence between the Crips and the Bloods. In 1987, the LAPD implemented the Operation Hammer program to take back the streets. In April 1988, more than 1,450 people were arrested on a single weekend.

Yet community activists began pushing back on the controversial racial profiling tactics and police brutality overseen by then-Chief Daryl Gates, who in 1992 received heavy condemnation over his tepid response to the savage videotaped beating of a Black man, Rodney King, by white police officers. A jaw-dropping acquittal later that year would spark the L.A. uprisings.

Ice-T, whose searing “Colors” placed a nuanced spotlight on L.A. gang life, and N.W.A proved to be prophetic.

“They were our brothers who were feeling the same vibrations we were feeling in New York,” says Shocklee, who would go on to produce Ice Cube’s 1990 solo debut, “AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted,” as part of the Bomb Squad. “That’s why Public Enemy resonated with Ice-T and N.W.A. The energy of hip-hop was never passive. It was always on the offense.”

This story originally appeared on LA Times