Two sisters. Two American dreams. Two very different results.

Maria Del Pilar Barradas-Medel and her older sister Maria Del Consuelo emigrated from Mexico nearly three decades ago. They wanted, more or less, a better life for themselves and the families they hoped for. They wanted schools and jobs — where they could make more than $5 a day — and an end to daily struggles in their home on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Maria Del Consuelo would last only a few months in Southern California, forced back home to care for their ailing newborn sister — child No. 10 in their poor, sprawling family.

Barradas-Medel stayed in the Los Angeles suburbs with her husband, Alejandro Medel. She is glad she did. Maria Del Consuelo wishes she could have too.

Maria Del Pilar Barradas-Medel works as a file clerk in a law firm, a job she says she could not have obtained had she stayed in Mexico.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Here, Barradas-Medel worked her way up from nanny to cleaning lady to file clerk in a law firm. Here, her husband went from washing cars to starting his own landscaping business. Here, her children far surpassed her own education, graduating from high school and pursuing more advanced degrees.

Barradas-Medel’s salary is humble, and the family of five has to squeeze into a one-bedroom mobile home in Azusa. But it’s a better life than she could have imagined back home. And it has allowed her to help her extended family in Valle de Chalco.

“I would do it again,” she said of her trek north half a lifetime ago. “Definitely.”

Immigrants to the U.S. face extensive challenges, including widespread discrimination and economic hardships. Many report struggles in their daily lives. Nonetheless, Barradas-Medel’s emphatic yes speaks for a large majority of immigrants surveyed earlier this year in a groundbreaking nationwide poll conducted by The Times in partnership with the nonprofit KFF, formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The poll, conducted in 10 languages using a rigorously developed survey method, was designed to fill significant gaps in what’s known about the roughly 1 in 6 U.S. adults who were born in other countries. Its size and comprehensiveness allow comparisons among immigrants of different national origins and among varied locations in the U.S. that were previously unavailable.

This is the first of many stories The Times plans to publish based on the survey’s major findings.

Alejandro Medel went from washing cars to starting his own landscaping business after coming to the U.S.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Like Barradas-Medel, who was among the poll respondents who agreed to follow-up interviews, the vast majority of immigrants say they came to the U.S. seeking better economic and job opportunities and a better future for themselves and their children.

Most say they’ve found both.

Eight in 10 immigrants surveyed said their financial situation was better because of moving to the U.S., and roughly 8 in 10 said educational opportunities for themselves or their children have improved because of immigrating.

Eight in 10 also said if they could go back in time and do it all again, they would still choose to emigrate.

And 7 in 10 who are parents said they expect that their children’s standard of living will exceed their own.

That sort of optimism was once considered an American hallmark, remarked on by commentators going back as far as the early 19th century.

In recent decades, though, that’s changed. Scholars and pollsters have charted a striking rise in national pessimism. The shift has been driven primarily by white Americans, who have grown more gloomy in most years since 2000, except for an uptick during the Trump presidency, according to data from the annual General Social Survey, a leading academic-based poll, analyzed by NORC at the University of Chicago.

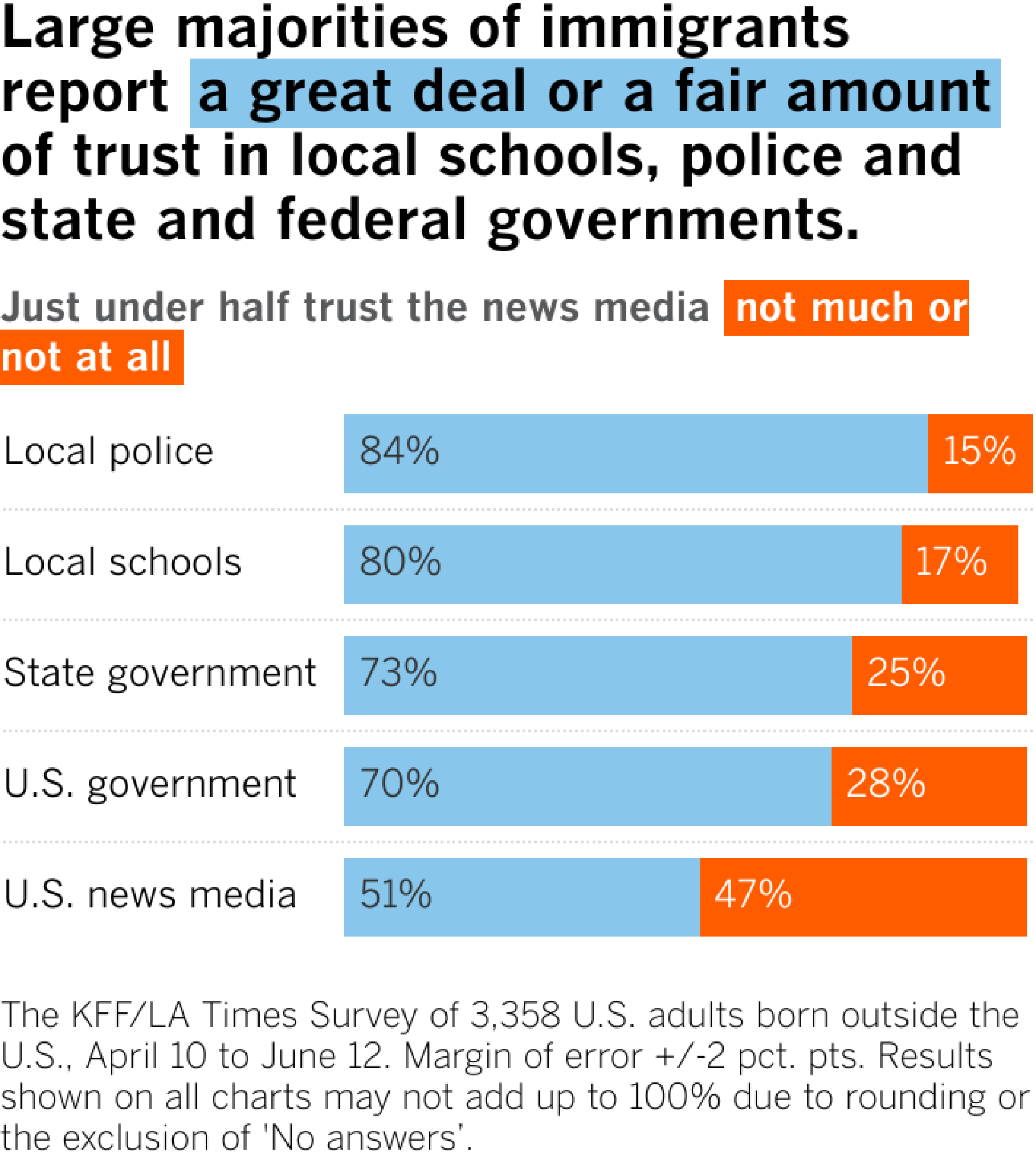

Trust in American institutions has also dropped, hitting historically low levels among the population as a whole, according to polls by Gallup and others.

Among immigrants, by contrast, large majorities report at least a fair amount of trust in local schools, police and state and federal governments, the KFF/L.A. Times survey shows.

On both those measures — optimism and social trust — immigrants are upholding attitudes once widely seen as central to the American creed.

Immigrants give many reasons for coming to the U.S., but by a substantial margin, the top two are to obtain better opportunities for themselves and a better future for their children.

1

2

3

1. Maria Del Pilar Barradas-Medel has her morning coffee before heading to her job. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 2. Alejandro Medel prepares breakfast for his family at their Azusa home, something he does every day. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) 3. Alejandro Medel with his 4-year-old son, Anxelo, at their home. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Immigrants surveyed also cited greater rights and freedoms this country affords and the need to get away from unsafe or violent conditions in their homelands. Escaping unsafe conditions was cited as a major reason by half of those who have neither citizenship nor a green card and 6 in 10 of those from Central America.

The immigrants interviewed by The Times held a wide range of status under U.S. law. Some obtained citizenship through family members, others were winding through the asylum process or on temporary visas. Others were living in the country without legal authorization, in some cases for many years. Those who lacked legal status talked of losing jobs because of it and fearing deportation.

Immigrants living in the U.S. without legal status are significantly more likely to report economic difficulties and discrimination in their workplaces.

Fabio Gutierrez, 28, arrived in L.A. nearly two years ago, fleeing political persecution in Nicaragua.

“People were dying, disappearing,” he recalled. “Things got really bad … life is easier here.”

Yan Xiang, 43, left China for Pittsburgh nearly 20 years ago seeking better opportunities for herself. Gennyfer Leguizamon, 41, followed her husband — who got citizenship through his mom — from Colombia to L.A. for the sake of their children.

“My two kids are going to have the opportunity to enter into a university and make a life that’s much better than ours,” said Leguizamon, who arrived in 2019. “I know they’re going to have a better future than us.”

Phuong Ton, 41, wound up staying in the U.S. unintentionally. In Vietnam, she had a good job as an executive assistant for a Canadian insurance company. She owned a home.

Ton and her then-toddler son traveled to Texas on a tourist visa in 2018. Months into her visit, she learned her father, who had immigrated several years earlier, had colon cancer. He lived in Houston. Her older sister lived in Austin. There was no one to care for him.

So she stayed. As her father’s condition improved, she thought of going back. Then the pandemic struck. Nearly all travel was frozen.

Now, she works 36 hours a week as a clothing salesperson in Houston, raising Benjamin, now 7, as a single mother in a three-bedroom apartment she shares with a roommate. Rent is about $900 a month.

Ton said she doesn’t regret the decision to stay because of the “bright future” for her son.

“The educational system is better here, and all the benefits for children are much better here,” she said, making the decision an obvious choice.

Aaron Tong was sent to the U.S. from Chengdu, China, by his parents specifically to further his education. He had just missed the cutoff on his college entrance exam to enter a top-tier school. His dad decided the teenager should start over in the U.S.

Tong attended Purdue University, where he studied mathematics. After getting a master’s degree, he moved to Irvine in 2016. A few years later he got into sales. The 34-year-old now makes $180,000 a year as a general manager for a car-parts company.

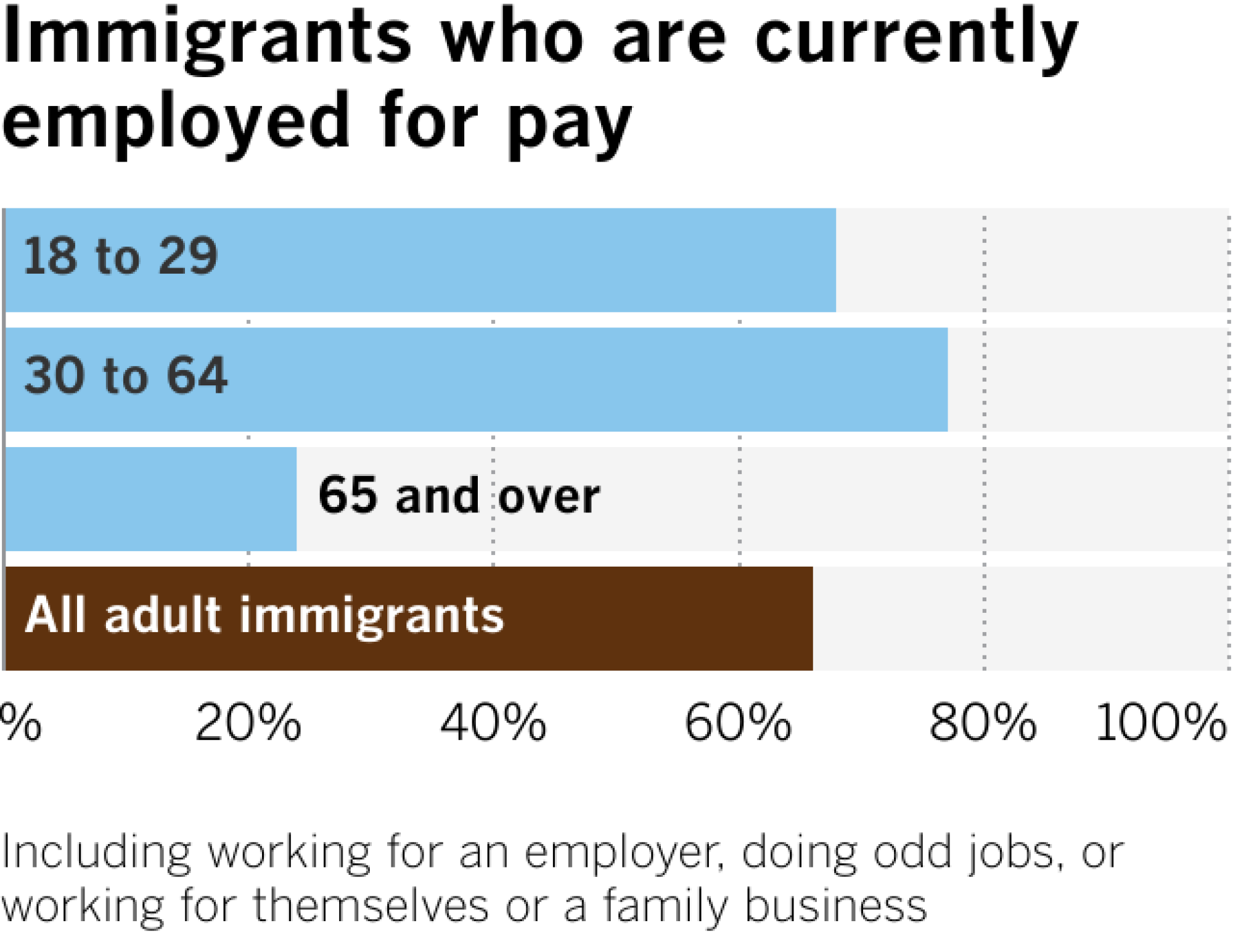

Like Tong, most immigrants work. Two-thirds said they are currently employed. Most of the rest are either students or retirees.

Although Tong has faced anti-Asian hate incidents — a woman yelling at him to “go back to your country” and another telling him that people like him “brought COVID” — he thinks life is better here.

“The U.S., if you want to earn money, start your own business, you want to be famous, you just work hard and that’s it,” he said. “There’s no boundaries. … You can do whatever you want. Everybody’s the same. Everything’s equal.”

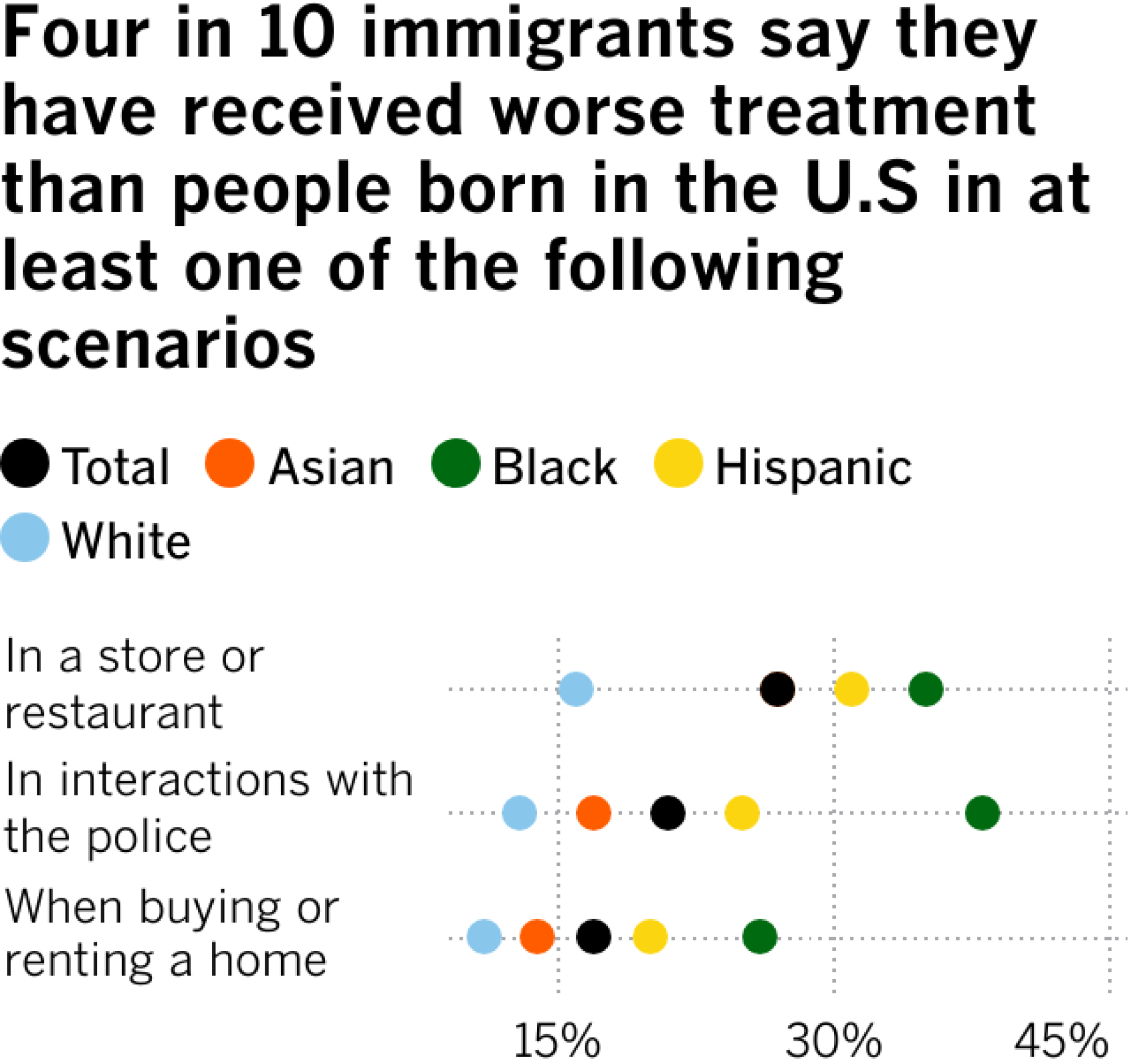

Not every immigrant has so positive a view. Black, Latino and Asian immigrants are more likely than white immigrants to report unfair treatment at work, such as being paid less than others for the same work or having fewer opportunities for advancement, the survey found.

Four in 10 immigrants said they have received worse treatment than U.S.-born people in stores or restaurants, in interactions with police, or when buying or renting a home. That share rises to 55% among Black immigrants.

One-third said they have been criticized or insulted for speaking a language other than English. A third said they have been told to “go back where they came from,” including nearly half of Black immigrants.

Sanika Fennell, a native of Jamaica who became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 2022, said that while most white people where she lives in Killeen, Texas, have shown kindness toward her, she lives with the knowledge that being Black in America means always being prepared to be treated unfairly — even in mundane situations.

A real estate agent who’s also a combat engineer at Ft. Cavazos, Fennell recalls being challenged by a white cashier one day when attempting to make a large purchase at a store in her city.

“‘How are you going to pay for these things?” the cashier asked while in the middle of ringing her up.

“If it was a white person, she wouldn’t have stopped to ask that question,” Fennell remembers thinking.

She confronted the cashier.

“You’re underestimating the power of my purchase,” she said and walked out of the store, leaving her merchandise behind.

Juan Mata has also experienced his fair share of struggles since emigrating from Matehuala, a city in the mountains of San Luís Potosí, in central Mexico. By the 1980s, two of his sisters had moved to McAllen, Texas, on the border, and they encouraged him to come north.

Mata had long been frustrated with his job prospects. Even if he stayed in Mexico, he knew he’d have to move west to bustling Guadalajara to find a worthwhile job.

“They kept insisting —‘come on, come on’—and eventually they convinced me,” Mata said.

He was unimpressed by what he found — a job picking oranges in an old orchard, with tall, wiry trees. Picking the small amount of fruit meant working until late into the evening. It confirmed his suspicions that the promises of the U.S. — high wages and an opportunity to climb the socioeconomic ladder — were exaggerated.

He’s not alone in finding the costs of living in the U.S. daunting. Financial and economic worries and bills were by far what immigrants mentioned most when asked about their biggest concerns.

One-third of immigrants reported problems affording necessities such as food, housing and healthcare. That rose to 4 in 10 among immigrants who have children. Among those who are probably living in the U.S. without legal status or who live in a lower-income household, about half reported such difficulties.

Almost 40 years later, Mata is retired and living in Dallas’ Oak Cliff, a neighborhood well known for its Mexican population. He said he’s not optimistic about the direction the U.S. is headed.

“It’s getting more expensive every day, and yet there’s less and less work,” he said.

He often has hard conversations with his family about whether he should move back to San Luís Potosí, but one factor makes his decision to stay in the U.S. easier: danger in Mexico. Friends and family back home have to contend with powerful criminal groups, who exploit residents for “taxes” — payment for safety — he said.

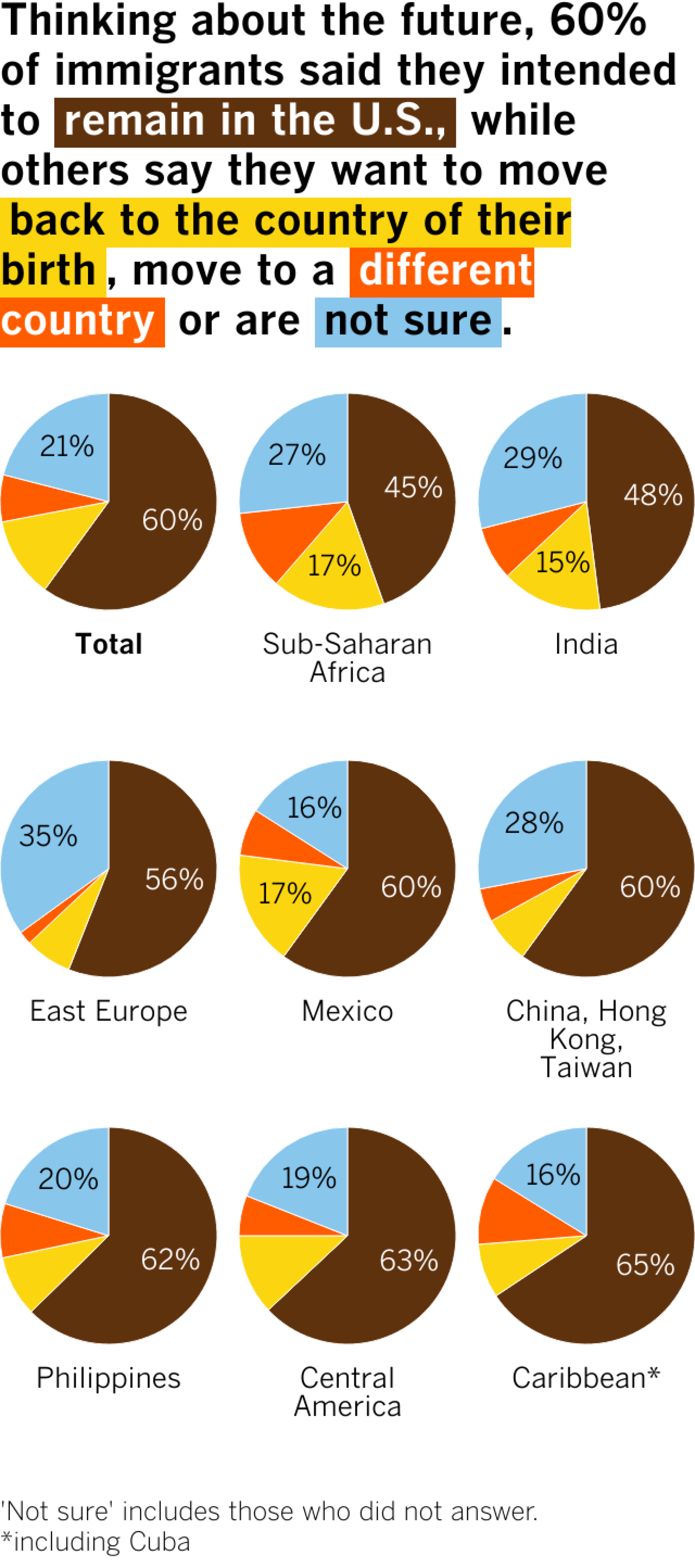

In the survey, 60% of immigrants said they intended to remain in the U.S. But 1 in 8 said they want to go back to the country of their birth, and 21%, like Mata, said they’re not sure.

Close to one-fifth of Mexican immigrants said they want to move back to Mexico. More than 100,000 Mexican residents of the U.S. do move back each year, according to statistics from the U.S. and Mexican governments, largely offsetting, and in some years exceeding, Mexican migration into the U.S.

When asked if he regrets immigrating, Mata said he’d do it again. But he doesn’t have a romantic attitude about the States or Mexico: It’s a struggle to live in either one.

In their three-bedroom home in San Mateo, Johnny and Yvonne Wong keep reminders of the successes — not the struggles — that followed their immigration from Hong Kong to California in 1992.

Atop their fireplace is a photo of their son Calvin in his cap and gown, smiling for his UC Irvine graduation photo. Yvonne’s blue Mercedes SUV bears a Wharton license frame — representing the MBA Calvin earned at the prestigious business school.

Calvin Wong climbs at a gym near his home in San Mateo, Calif. The avid rock climber and child of immigrants appreciates all his parents have done for him.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Decades ago, Yvonne asked her husband about moving Calvin to the U.S. At the time, their son was 7 and already carrying half a dozen thick textbooks in his backpack. His parents knew the life ahead in Hong Kong: long days and nights of studying for a do-or-die college entrance exam. Crushing pressure. Conformity.

They went through that life. They wanted something different for Calvin.

“It wasn’t a complex discussion or conversation,” said Johnny, 69. “She raised the point about his education, and I was like, ‘I support it 100%.’”

Life in the U.S. came with sacrifices. Yvonne and Calvin moved to California. Johnny stayed behind to continue his work as a management consultant in Asia and take care of his mother.

Until Johnny semi-retired and came to the U.S. seven years ago, he saw his son in person only two or three times a year for about two weeks at a time. He missed memories that Calvin still holds dear — like the Halloween when he dressed up in a yellow Wolverine costume.

1

2

3

1. Johnny Wong prepares dinner at his home in San Mateo, Calif. Wong stayed in China until seven years ago while his wife and son were in the U.S. (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times) 2. Yvonne Wong, playing badminton in San Mateo, said of her life in the U.S.: “We are not rich, but we have a rich life. Life is simple, plentiful, happy.” (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times) 3. Calvin Wong sees an analogy between his life in the U.S. and rock climbing: “In climbing, there are static movements where you move slowly to get to the next goal. There are dynamic movements where you have to go for it — jump and go somewhere far away.” (Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Yvonne missed her husband, but she too had to adjust. In Hong Kong, she had worked up the ladder to be an assistant branch manager at a bank. She did not want to take a junior position in the U.S. But she said she realized seniority doesn’t matter as much in the U.S. as long as “you are capable.” She took the job.

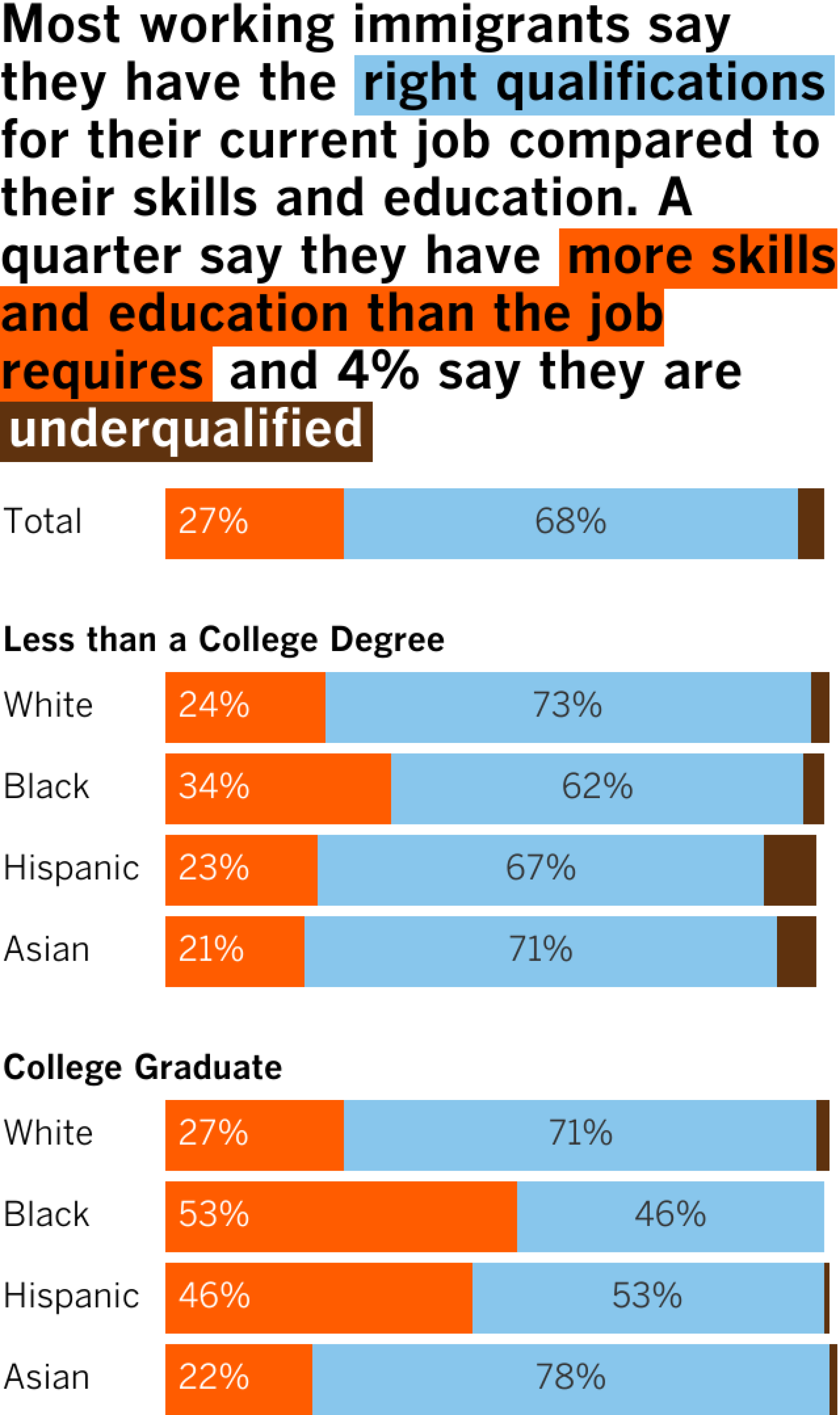

Most working immigrants, 68% of those surveyed, said they feel they have the right qualifications for their job, but about a quarter said they feel overqualified, having more skills and education than their job requires.

As Johnny prepared lunch on a recent afternoon for himself and Yvonne — pork spare ribs, soy sauce braised salmon, deviled egg salad and pan-fried shrimp — he said he tried “to appreciate the good side of everywhere.”

“If you are always complaining, that’s not good,” he said.

Yvonne stood next to him, giving instructions in Cantonese as she chopped bell peppers. An old Canto-pop ballad played on an iPad.

Since fully retiring a year ago, Johnny finds joy in family mah-jongg sessions on Saturday afternoons, regular qigong classes at a park, gardening in the backyard and learning how to cook Chinese food from Yvonne and myriad YouTube videos.

“We are not rich, but we have a rich life,” Yvonne said. “Life is simple, plentiful, happy.”

Calvin, who works as the senior director for the professional services firm Aon in San Francisco, said he appreciates what his parents have done for him.

He drew a parallel between his life and rock climbing, a hobby he’s passionate about.

“In climbing, there are static movements where you move slowly to get to the next goal,” he said. “There are dynamic movements where you have to go for it — jump and go somewhere far away.”

On a recent morning, the sun hadn’t yet risen when Barradas-Medel and her husband started their day.

In the kitchen, Medel chopped tomatoes, jalapeno and onion for huevos rancheros. He didn’t have a landscape job until 9:30 a.m., but woke up early to make breakfast for the family as he does every day.

The Barradas-Medel family sits down to breakfast in their one-bedroom mobile home in Azusa. “I would do it again,” Maria Del Pilar Barradas-Medel said of immigrating to the U.S.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Hanging on a wall near the kitchen was their daughter Alexa’s pencil-drawn portrait of a young man, which helped her place in the 2022 Congressional Art Competition. Barradas-Medel accompanied her to D.C. — Alexa’s first time on a plane — to accept the award. In the living room, near his bed, Alexander had stacked boxes of Nike and Adidas shoes he bought with the money he saved working at the law firm with his mother.

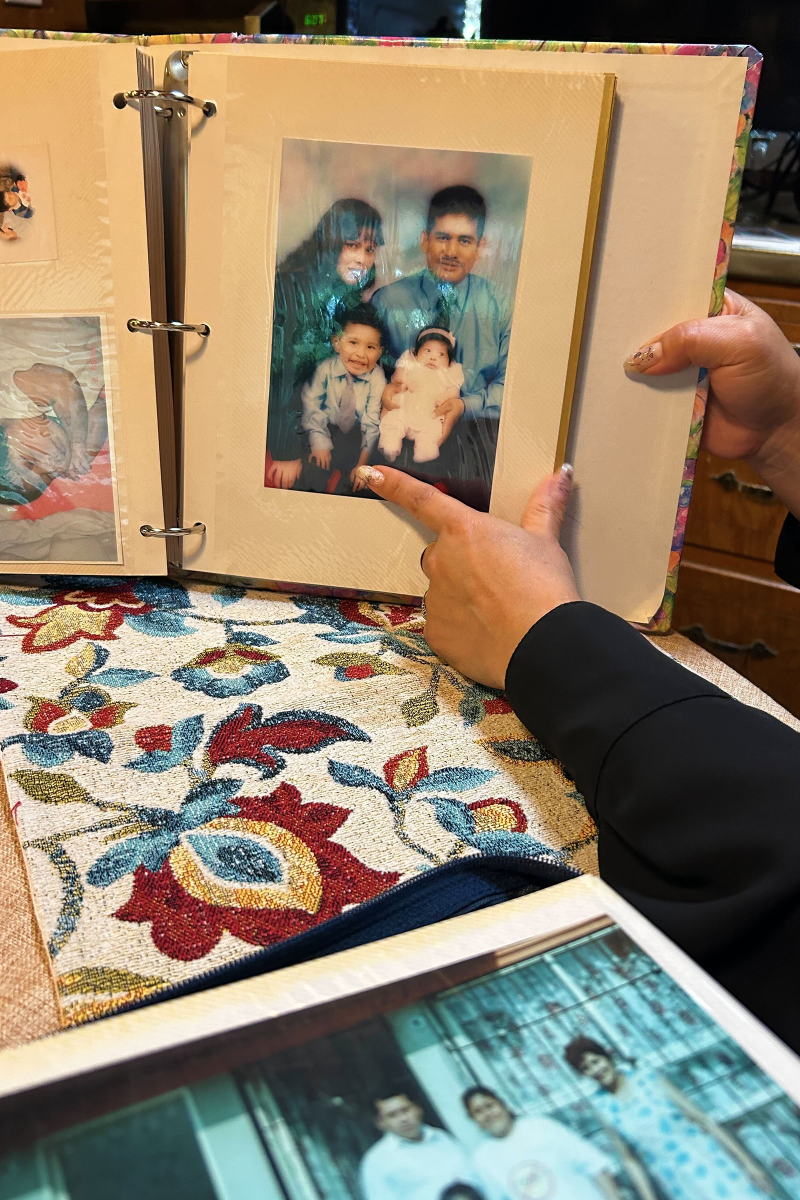

Barradas-Medel, who arrived in California in 1994, often tells her children that the lives they lead are a world away from the one she had in Mexico. There, she dropped out in middle school to work as a maid to help with bills. An older and a younger sister also had to drop out. Here, Alexander obtained his associate’s degree, and Alexa recently started community college and plans to transfer to a university.

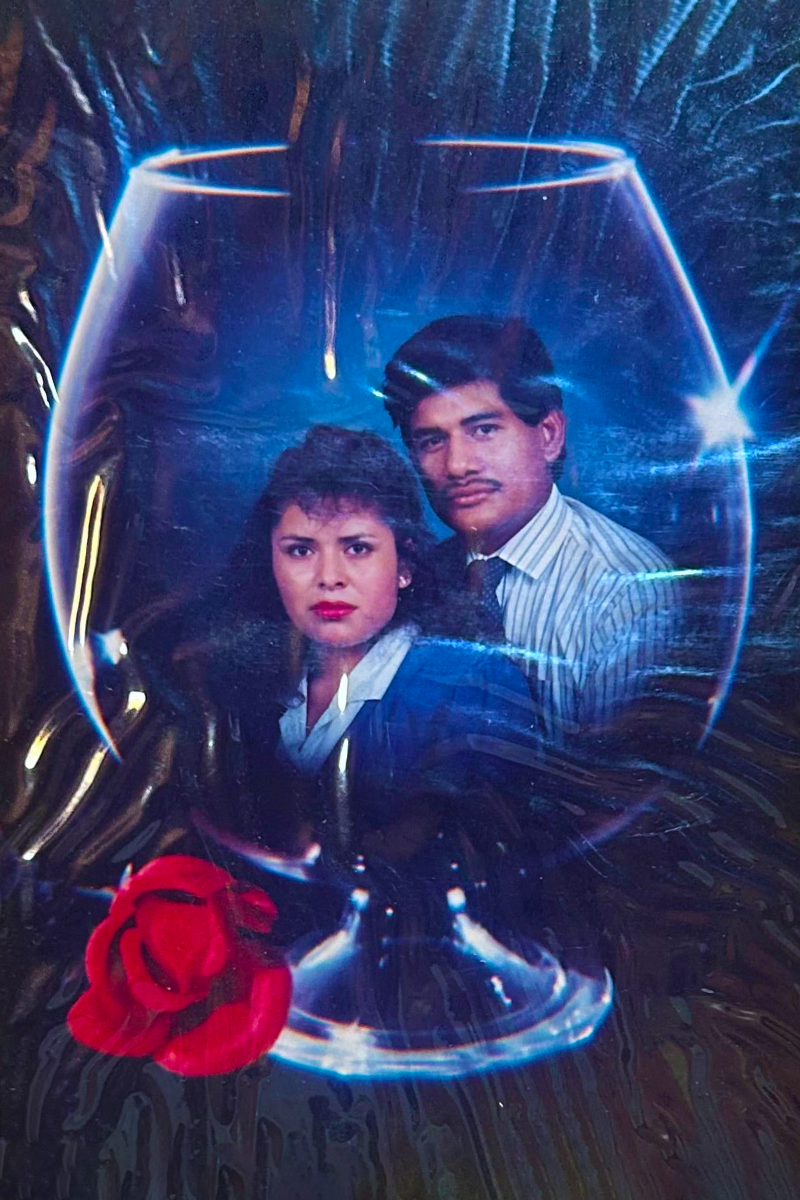

(Maria Del Pilar Barradas-Medel and Alejandro Medel)

“We’re always telling our kids they need to study,” Barradas-Medel said. “They’re going to have a better future studying.”

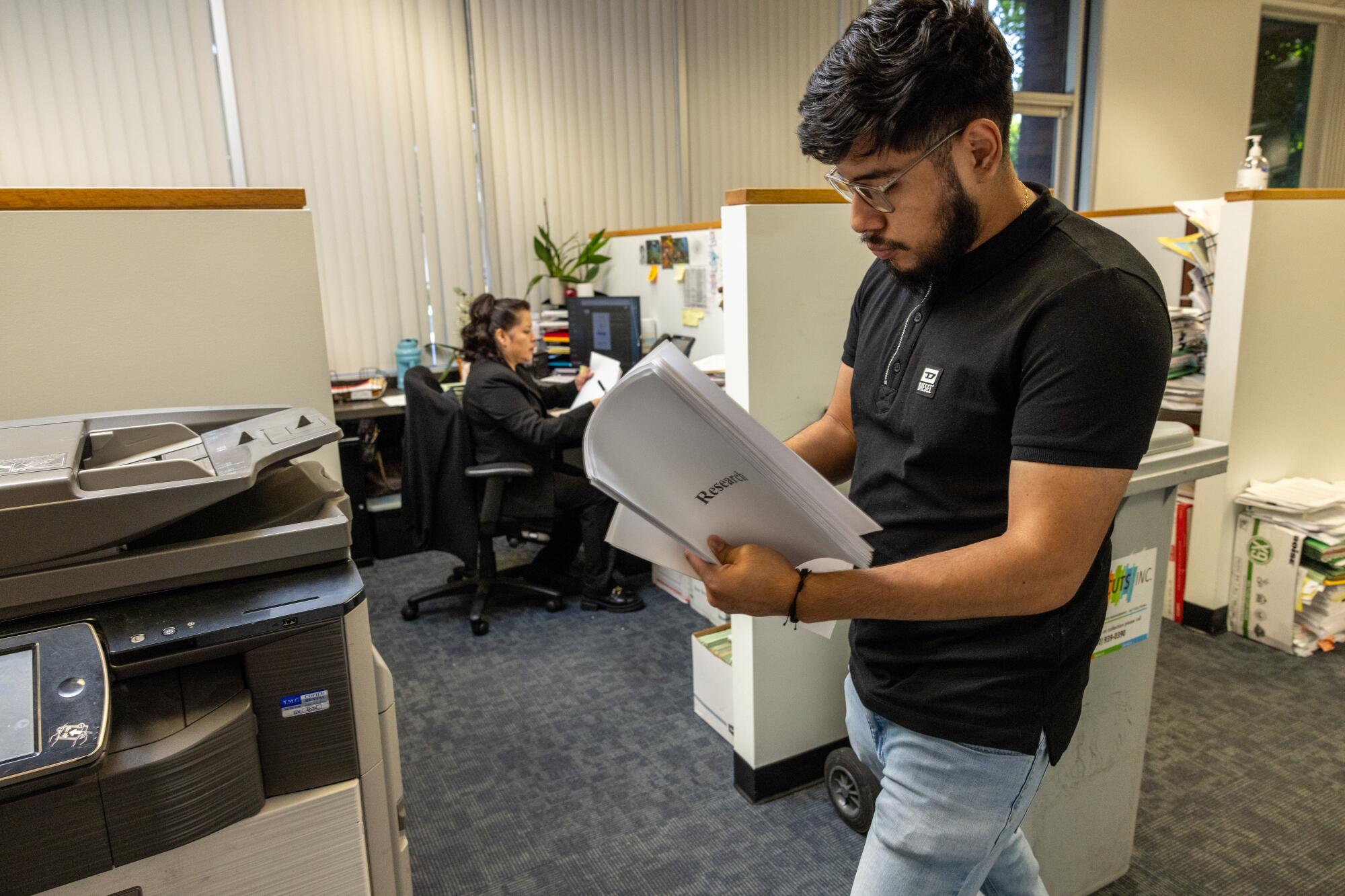

As Medel cooked, Barradas-Medel, dressed in slacks and a black shirt embroidered with a red rose, packed chicken and potato quesadillas, soup and salsa for herself and Alexander. Soon, the two would head to the law firm, where Barradas-Medel has worked for 11 years.

When Barradas-Medel was first hired, she had no experience and needed help to turn on the computer. Now, “she runs this office,” a paralegal said during a recent workday.

Barradas-Medel, who works in the archives, is one of the clerks responsible for maintaining case files. With every meeting and hearing, she updates the physical and digital files so the lawyers have everything they need.

By now, she knows where all the boxes are kept for different cases, and she prepares physical files weeks ahead of scheduled court hearings. Her small cubicle — decorated with pictures that her 4-year-old son, Anxelo, colored — is as well organized as her closet at home.

Maria Del Pilar Barradas-Medel and her son Alexander, 20, work in the law office in Arcadia where she has been employed for 11 years.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

In Mexico, “I never would have been able to get into a job like this one,” she says.

Her success has benefited family members on both sides of the border.

When Barradas-Medel began sending money back to Mexico — at least $100 each month — she had her mom stop working as a maid. No more of her siblings had to drop out of school to help pay the bills. Close to half of all immigrants said they send money to relatives or friends in their country of birth at least occasionally.

Her older sister, Maria Del Consuelo, said Barradas-Medel is someone who “always looks out for the family.” She credits the financial support as the reason why her son is enrolled in a university.

“Pilar is an unconditional and unique support,” Maria Del Consuelo said. “If she weren’t over there everything would be very different. Thanks to her and her effort, we’ve achieved a lot as a family.”

Maria Del Pilar Barradas-Medel and Alejandro Medel, with son Anxelo, are among a majority of immigrants who are optimistic about this country.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Barradas-Medel, a naturally positive person, tries to live by the decal painted on her nails: “Be happy and smile”

After all, there will always be something to worry about. Rising inflation. The well-paying job Medel lost because his longtime clients decided to move. The larger homes that remain out of their price range.

But none of it could change Barradas-Medel’s mind about the decision to leave Mexico so many years ago.

“We haven’t accomplished everything,” she said, “but we have a better life than we did in our country.”

Times staff writers Tyrone Beason and Anh Do contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared on LA Times