The Tuolumne County Public Health Department on Wednesday confirmed two measles cases a day after it opened an investigation into the possible infections.

The department said the cases involved an adult and a child under 18 who lived in the same household and had traveled internationally. It’s unclear whether the individuals had been vaccinated against measles, a highly contagious and potentially deadly disease most often associated with a high fever and rash.

On Tuesday, the department said it was investigating the cases for measles and warned of potential exposure at Summerville High School in Tuolumne between March 10 and 11 and at Adventist Health Sonora Emergency Department between the evening of March 15 and morning of March 16.

“We understand that there may be a lot of questions and concerns. The investigation is still ongoing, and we will provide updates as they are available,” Michelle Jachetta, the county’s public health director, said in a Wednesday statement confirming the cases. “We want to remind the public that measles is a highly contagious disease and to take steps to protect yourself and your family by ensuring current vaccination status for measles, monitoring for symptoms, and staying home when you feel sick.”

Michael Merrill, superintendent of Summerville Union High School District, also issued a statement this week saying the district “takes the health and safety of its students, staff and our community seriously” and that the school would work with public health officials “through the process of identifying any risk.” More than 430 students attend Summerville High School, according to its website.

Tuolumne County’s cases come amid a deadly measles outbreak that began in the South Plains and Panhandle region of Texas in January and has since infected 279, making up the vast majority of more than 300 confirmed cases across 15 states so far this year. An unvaccinated school-aged child in Texas died from the disease in February.

The California Department of Public Health reported Thursday that there have been at least eight confirmed cases of measles in the state this year. They have not published the locations of the cases.

Tuolumne County reported some of the state’s lower vaccination rates in the 2023-2024 school year, according to data published this week by the state public health department.

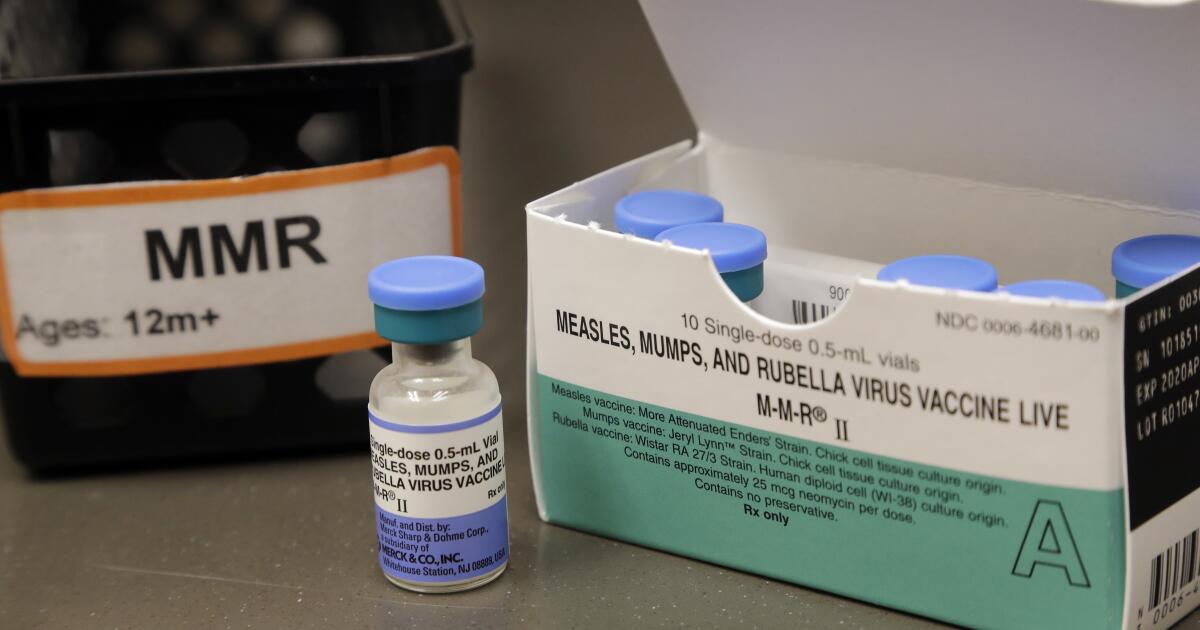

Only 89.8% of Tuolumne County kindergarten students were up to date on all their immunizations, compared to 93.7% of kindergartners statewide. And only 93.1% of kindergarten students had received both doses of their measles, mumps and rubella shots, substantially lower than the 96.2% statewide average. California typically publishes vaccination rates for a handful of grades, including kindergarten, first grade and seventh grade.

Public health experts say a 95% vaccination rate, sometimes called “herd immunity,” is generally considered the gold standard of disease prevention. A slip of even one or two percentage points can create an opportunity for disease to spread, meaning that even if the overwhelming majority of children are vaccinated, it could still take only a few cases to spark an outbreak in an area where immunization rates have fallen below 95%.

California reported a decline last year in the share of kindergarten students who were immunized against measles, despite strict laws that make it difficult for parents to skip shots for their children. That includes 16 counties where measles immunization had fallen below the herd immunity threshold.

An increase in vaccine hesitancy in recent years, coupled with widespread disinformation online and increasing political division, could make it even harder to encourage immunization, said former state Sen. Richard Pan, a Sacramento Democrat who wrote California’s vaccine laws.

“We seem to be heading the wrong direction,” Pan said. “We’ve been feeling pretty comfortable, like ‘we’re OK.’ But we suddenly now prove to people, it’s not OK.”

This story originally appeared on LA Times