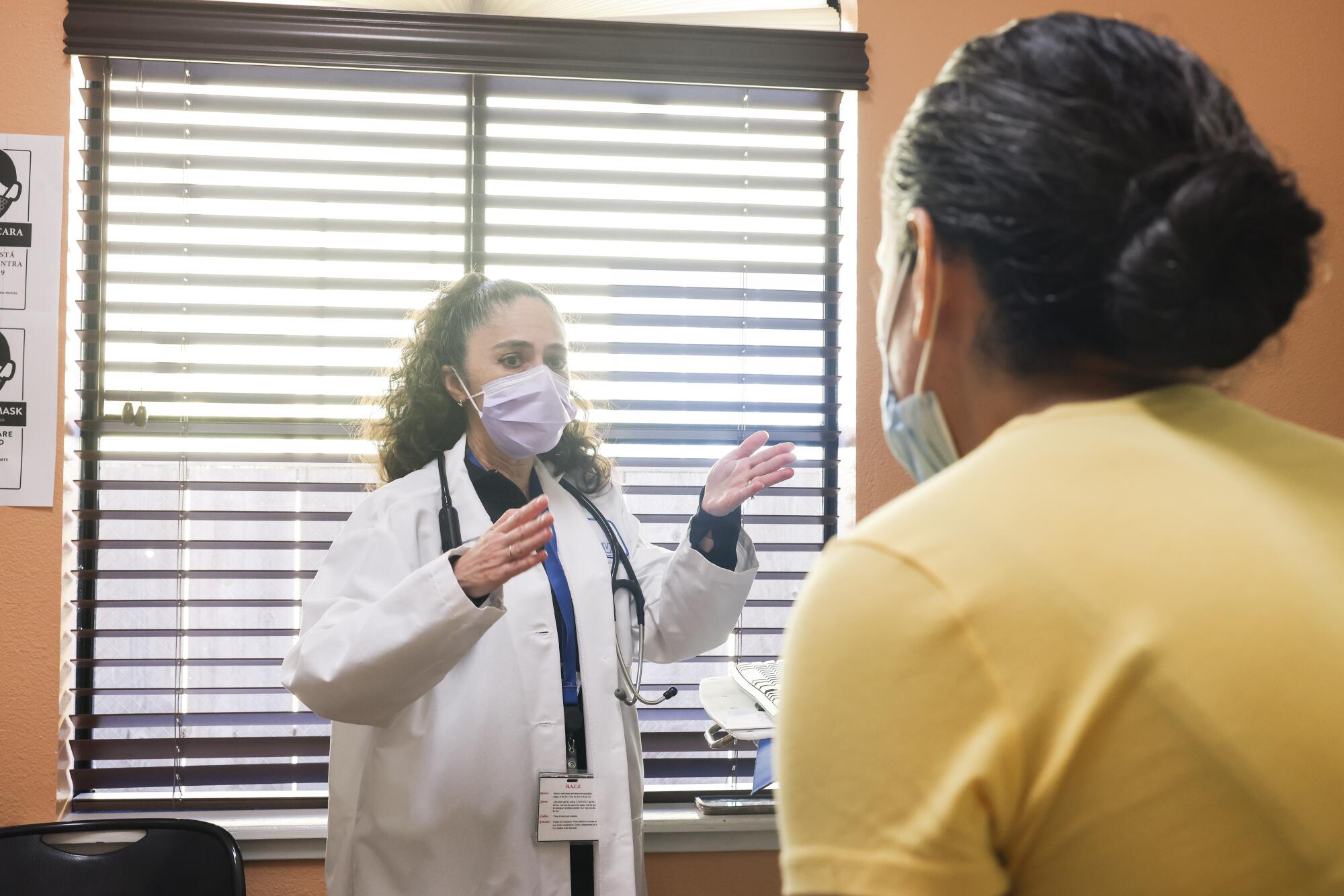

Neri Ortiz tucked her hands in her lap as she earnestly recounted her latest health episode to Dr. Eva Perusquia.

Recently at work, where Ortiz packages vegetables overnight, she was hit with a wave of nausea and tears. She managed to pull herself together enough to continue her shift, she told the doctor. But it had been years since she’d experienced such an overwhelming emotional surge.

Perusquia listened closely. Ortiz, 42, had been her patient since last year, after she sought out a Spanish-speaking physician at the Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas. Perusquia had been the first doctor to explain her hypothyroidism and why she needed to take a thyroid medication to regulate the condition. Ortiz knew the doctor would understand how she felt.

Perusquia said the spike in emotion could be related to Ortiz’s glucose levels, which can cause mood swings. She would order tests to see whether Ortiz’s levels were normal.

Dr. Eva Perusquia, trained in Mexico, examines Neri Ortiz at the Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas. After years of seeing different doctors, Ortiz said, having Perusquia explain everything in Spanish has been a welcome change.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Ortiz was grateful. Having Perusquia explain everything in Spanish was a welcome change after years of going to different doctors. Before, English-speaking doctors had left her confused and doubtful that she understood their instructions.

“I understand everything. She explains it all clearly,” Ortiz said.

A 2002 state bill — which took nearly two decades to implement — made it possible for Mexican doctors such as Perusquia to work in California amid a chronic shortage of Spanish-speaking physicians. Latinos make up about 40% of the state population but just 6% of licensed physicians. The language and cultural gaps are felt most acutely in the vast rural stretches of California’s Central Coast and Central Valley, where immigrants from Mexico and Central America are integral to the farming economy. Hospitals and healthcare clinics that tend to farmworkers and their families routinely struggle to recruit and retain English-speaking physicians, let alone attract doctors who speak Spanish and Indigenous languages.

The Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas, a federally qualified health center that operates 13 clinics across farm country in the Salinas Valley, has taken a meaningful step to address the shortages. Clinic directors, in concert with health officials in California and Mexico, recruited doctors from Mexico and have deployed some to additional community health centers in Fresno, Kern, San Joaquin, Tulare and Ventura counties — all centers of agriculture whose farmworker communities have long been underserved.

Today, 24 Mexican doctors are working in these counties after being vetted by the Medical Board of California. The doctors specialize in pediatrics, gynecology, internal medicine and family medicine. If renewed, the groundbreaking pilot program could be extended and expand.

“This is something that has never happened before,” said Maximiliano Cuevas, chief executive of Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas. “We acknowledge the fact that this is not a cure-all, end-all for the problem our nation is facing, and that is a shortage of doctors.”

Still, he sees the effort as a crucial step forward in meeting the mission of community health centers: “We’re going to provide access to people who need healthcare,” Cuevos said. “We can bring in qualified doctors.”

Many of the Mexican doctors involved in the program said they see it as a civic duty, a way to serve their fellow countrymen and other immigrants seeking a better life in the U.S. They have found that their patients yearn for someone to talk to in their native Spanish.

Dr. Georgina Centeno said she finds her patients relieved to be treated by someone fluent in Spanish: “They tell me things that have happened to them, and they say, ‘Well, I’ve never been able to talk about it before, because my other doctor never understood me.’”

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Dr. Georgina Centeno, an OB-GYN who worked in Mexico City before coming to Salinas, said she’s had patients who open up about intimate health concerns and even sadness during the first appointment. “They tell me things that have happened to them,” Centeno said, “and they say, ‘Well, I’ve never been able to talk about it before, because my other doctor never understood me.’”

After their exams, patients often invite her for meals at their homes or church to express their gratitude.

The doctors trickled across the border from Mexico, heading past San Diego and Los Angeles. It was early 2021, and for many, their final destination would be the Salinas Valley, the “Salad Bowl of the World.”

Some left behind a husband or wife, while others brought along spouses and young children. They were seeking an opportunity to work in the U.S. and filling a need for labor — not unlike the farmworkers they were coming to treat. They could see the parallels between their lives and migrant fieldworkers who often fled poverty, hunger or violence and sought a new life in the north.

As they began taking on clients, the doctors said they felt the immediate weight of their work; mothers opened up about domestic abuse, teens spilled over with anxiety and depression. Their patients described difficult work toiling in the fields and the body aches that come with it. The trauma, both physical and mental, of the migrants who come into their modest exam rooms spills out of them almost as soon as the doctors begin asking in Spanish about their health, work and lifestyle.

Perusquia, a petite woman who wears her hair in a high ponytail, usually sets a timer for 15 minutes when she meets with patients to stay on schedule. But for her first checkup with Yolanda Torres, she allowed her patient to unravel her story over half an hour.

Torres, 58, explained how she had suffered a car accident and was receiving disability pay, but she had struggled to find a doctor to take her pain seriously; how one lab charged her $160 for an X-ray; how her pain persisted. Perusquia struggled to keep her shock from showing. She made plans for Torres to get the tests and procedures she would need to continue to qualify for disability payments.

“Si dios quiere, le veo en tres semana,” Perusquia said. “God willing, I will see you in three weeks.” After the visit, Torres said she was grateful Perusquia took the time to listen. The doctor used terms Torres hadn’t heard since she left Mexico years ago.

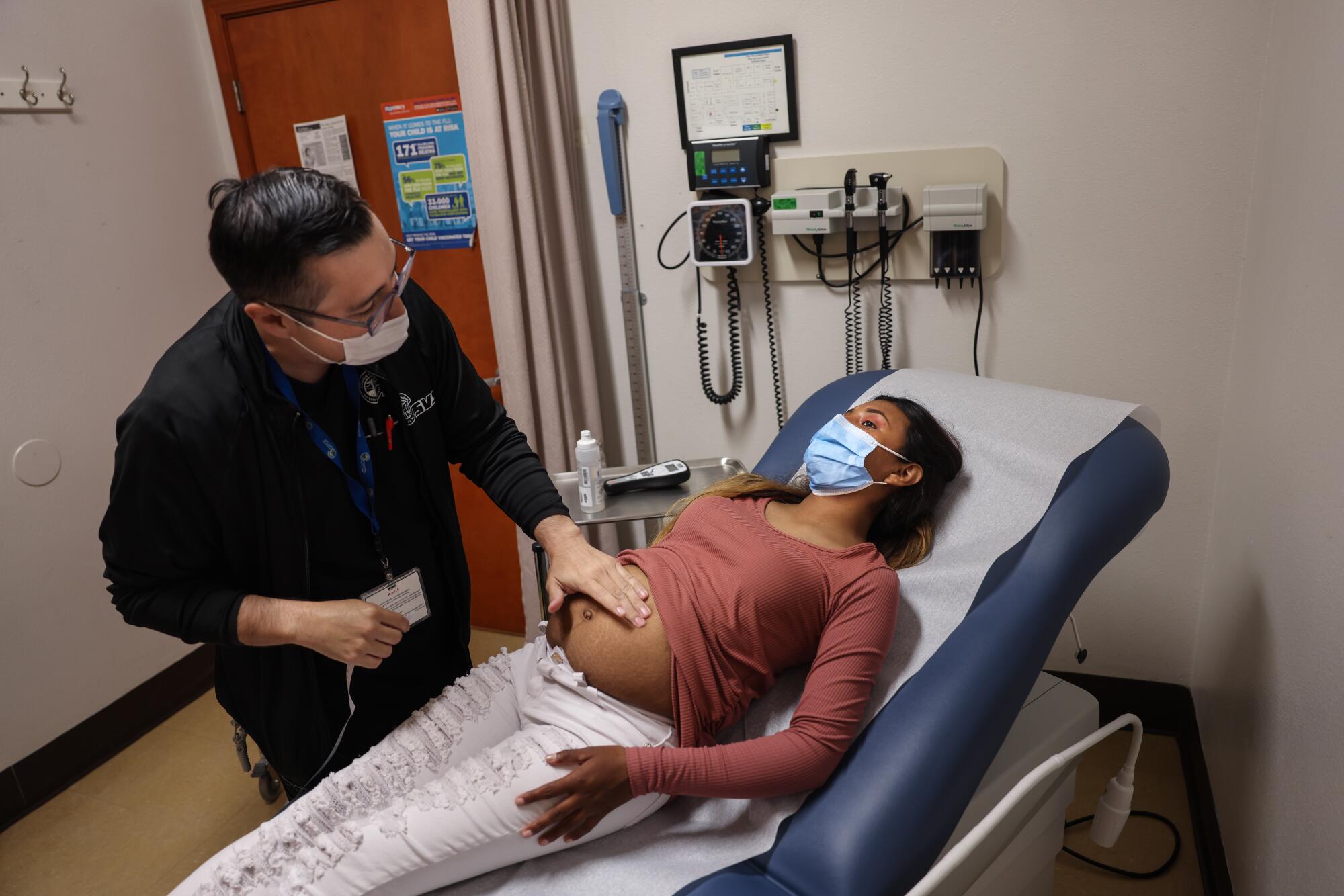

Andrea Lopez Hernandez, 20, arrived on a recent Wednesday for her monthly appointment with Dr. Armando Moreno, an OB-GYN. He spritzed hand sanitizer into his palms and rubbed his hands together as he updated Hernandez on the latest test results for her baby.

“Gracias a dios, todo ha ido bien,” he told her. “Thank God, everything is going well.” At 20 weeks, Hernandez was halfway through her pregnancy and she had a name picked out: Ashley.

Dr. Armando Moreno is a Mexican physician in California as part of a pilot program for improving farmworker healthcare. Although the program is still being evaluated, he said there is no measuring what he and other doctors involved in the program experience every day.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

As she prepares to give birth to her second child, Andrea Lopez Hernandez said she’s comforted to have found Dr. Armando Moreno: “Everything he’s told me, I trust.”

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

“Vamos a escuchar su corazoncito,” Moreno said gently, using a diminutive of the word “heart” to explain they would listen to the baby’s heart with an ultrasound. He squeezed gel on her lower abdomen and a steady thrum filled the room.

“Muchas felicidades, se escucha todo muy bien,” Moreno said, congratulating her on a healthy baby.

For Hernandez, a native of Hidalgo state, having access to Moreno eased her anxiety that she might be misunderstood. She recalled an episode where she was experiencing stomach pain and sought treatment at a hospital. An interpreter helped navigate the visit, but had an accent that made it difficult for Hernandez to understand what the doctor was trying to convey.

“I asked questions, but they couldn’t explain the answers really well to me,” she said.

Hernandez picks field lettuce, a taxing job she started in May. Previously, she worked in Utah, painting houses. As she prepares to give birth to her second child, she said she’s comforted to have found Moreno, who can guide her in her native language.

“It’s different with this doctor,” she said. “Everything he’s told me, I trust.”

Building trust is part of the reason the clinic fought so hard to get the program launched.

“I keep hearing over and over stories of people who have put off healthcare because they felt that no one was listening, that doctors were making fun of them because they couldn’t speak the language, or doctors were insulting them,” Cuevas said.

But getting from conception to reality was a frustrating and wearying campaign.

The California Legislature approved a pilot program for recruiting doctors from Mexico in 2002, laying out basic requirements the doctors needed to meet and an application process. But the California Medical Assn. and Latino physicians in the U.S. mounted opposition, warning of a two-tiered system of care that would relegate farmworkers to doctors of lesser skills. The program stalled.

Latino physicians accused Cuevas and Arnoldo Torres, then executive director of the California Hispanic Health Care Assn. and an advocate for the program, of creating a “doctor bracero program,” a reference to the 1942 agreement between the U.S. and Mexico to send over laborers to work the fields and railroads during a labor shortage.

“There was quite a bit of opposition to this little idea to provide physicians in these rural communities,” Cuevas recounted. With no headway, they let the program rest for more than a decade.

By 2015, with the need for Spanish-speaking doctors growing ever greater, opposition to the concept had muted. Cuevas and Torres rekindled their efforts, traveling to Mexico to recruit doctors. The Mexican government was willing to oblige — on condition that the doctors they exported serve no more than three years in the U.S. The strict time limit helped allay concerns in Mexico about a permanent “brain drain” of medical talent.

Dr. Maximiliano Cuevas, chief executive of the Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas, worked nearly two decades to launch a trial program that brings in physicians from Mexico to serve farmworkers in California’s agricultural hubs.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Many of the patients that Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas serves are farmworkers integral to California’s agricultural economy.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

The visiting doctors’ salaries in California range by specialty, but start around $250,000 a year. The expense is covered by the Clinica de Salud health system, which is federally funded to serve low-income and uninsured residents. Cuevas said the Mexican doctors are paid the same salaries as clinic doctors trained in the U.S.

The program will be peer-reviewed at the end of the year by UC San Francisco and the Medical Board of California to ensure the doctors are providing care on par with physicians trained in the U.S. The review will determine whether the program will be extended for three more years.

There are early signs of success, Cuevas said, including the rate at which the doctors are seeing patients. The Mexican doctors are on track to handle an average annual patient load of 4,500 visits each, meeting expectations.

Monterey County, home to the Salinas Valley, has one of the largest farmworker populations in California. Nearly 90% of farmworkers in the state say Spanish is their primary language. But many also speak Indigenous languages including Triqui, Mixteco and Zapotec. It’s estimated that a third of farmworkers come from Indigenous communities.

If the program continues, Cuevas said, they will try to recruit doctors who speak those languages.

Dr. Olga Padron, who specializes in family medicine and works out of the clinic’s Greenfield office, has begun learning Triqui so she can better understand her patients. A native of Monterrey, she said she had never heard of Triquis before coming to Salinas.

Many of the patients that Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas serves are farmworkers integral to California’s agricultural economy.

(Dania Maxwell/Los Angeles Times)

She said that her youth and privilege led her to believe that Mexicans migrating north had abandoned their people instead of fighting for a better country. But coming to Salinas in 2021, she said, she realized that economic opportunities in Mexico aren’t equal, with Indigenous Mexicans far more likely to live in poverty.

“How were they going to save Mexico, Olga?” she recalled telling herself. “They were hungry. Mexico failed them, and that’s why they’re here.”

Last year, Padron hired a Triqui tutor to better understand her Indigenous patients. She carries a notebook filled with Triqui translations for body parts. Her colleague, Perusquia, has picked up words in Mixteco and has a napkin filled with translations. Words like “pain,” “head” and “thank you,” have become keys to connecting with her patients. In her office, she keeps a plastic pink rose that a patient gifted her.

“For them, it’s important to know that someone tries at least to know some of their words,” Perusquia said.

Neri Ortiz, right, said Dr. Eva Perusquia was the first doctor to help her understand her hypothyroidism and why she needed to take a thyroid medication.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

There have been trials for the Mexican doctors as they have made California home.

Dr. Nadia Arias, a pediatrician, was the first to arrive in February 2021. She remembers searching for a restaurant around 9 p.m., a customary dinner time in Mexico, her first night in Salinas. But every restaurant was shuttered and the town quiet. Confused, she texted Cuevas, asking where she could eat.

He apologized. Everything in Salinas closes early, he explained. Arias returned to her hotel.

Dr. Juana Lucio reviews medications with Maria Remedios at Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Perusquia arrived without family. The weekends are the toughest without her husband, she said. She spends Saturday nights on FaceTime with him, a tequila in her hand, a whiskey in his.

But the doctors, who were strangers before the program, lean on one another for support. And they have discovered a new skill: speaking in Spanish while typing up notes in English.

They’ve attended a Maná concert together and spent weekends watching movies and making group dinners. They gather for birthdays and turn to one another for medical advice. On a recent weeknight, some of the doctors gathered at a taphouse for drinks and dinner. They cooed over Arias’ daughter, Mia, who had learned to walk in her Salinas home.

Drs. Nadia Arias, from left, Olga Padron and Eva Maria Perusquia, all Mexican physicians working in rural California, regularly meet after work with other doctors in the program.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Dr. Juana Lucio, from Los Cabos, was the newest addition, having arrived in January. Six more are set to arrive by the end of the year. She joked that the most nervous she gets these days is when she treats English-speaking patients.

“I panic,” Padron agreed.

“Me too,” Moreno chimed in as others nodded. The group laughed.

The program’s future remains to be seen. But Moreno said there is no measuring what he and the other doctors witness every day: patients opening up at the sound of their native language.

“I don’t know if in the future the program will be reviewed positively or negatively,” he said in Spanish. “But for me, and all of us who see patients every day, to see how their faces light up when you come in and you say, ‘Hi, how are you? How can I help you?’ That, for me, I will carry with me.”

Times staff photographer Dania Maxwell contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared on LA Times