This Much We Know is the kind of film that digs into your neural network and rewires it ever so slightly so that you see the world a little bit differently. Based on the quasi-nonfiction book About a Mountain by John D’Agata, the new documentary is similarly structuralist in its approach, but with a more personal and emotional twist from filmmaker L. Frances Henderson. She narrates with a detached objectivity, giving you the facts about a teenager’s suicide more than two decades ago, and her own friend’s suicide; about a proposed nuclear waste repository in Yucca Mountain; about the city of Las Vegas and its unique, artificial oasis in the desert.

Seemingly disparate strands are woven together in this expertly edited and directed documentary. Henderson spoke with MovieWeb about the personal background behind the film, its exploration of grief and death, and the limits of knowledge itself.

Adapting John D’Agata

MW: This Much We Know is adapted from the book About a Mountain, and yet it’s also very personal. How did the book and your life lead to this film?

L. Frances Henderson: So, I lost my friend Sarah to suicide in 2005. And it was extremely unpredicted. I mean, she didn’t show any signs of depression that I saw. In fact, I had spoken with her a week before […] She was super happy, she wanted me to be the photographer at her wedding. And then I learned a week later that she took her life, and I was immediately — and I even mentioned this in the film — immediately thrown into this void of: There was a time in my life where everything was understood […] but there was this weird void that I was in where nothing made sense. Could I trust what I knew to be true before?

L. Frances Henderson: So five years later, my friend was recommending some books to me, and she recommended About a Mountain. And when I picked it up, I was more interested in it from an artist’s perspective, just how someone takes reality and writes about it. And John D’Agata is an incredible writer who writes in a very poetic way. It’s about Las Vegas. It’s about suicide. It’s about all these things that I was very interested in, because of my own friend’s life like that she took.

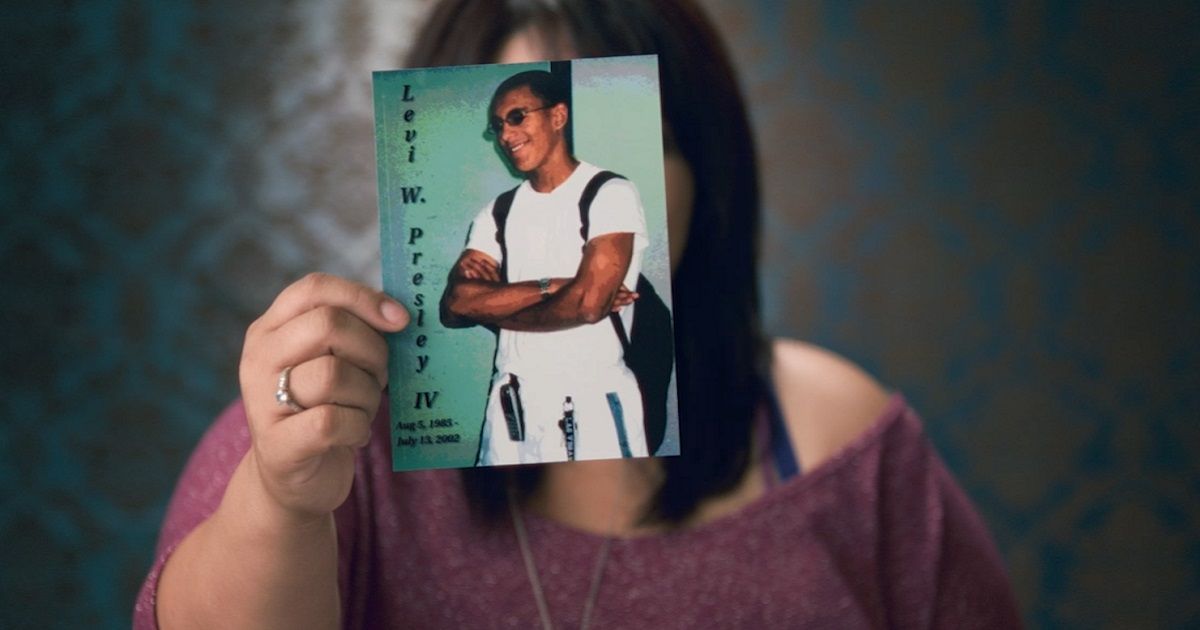

L. Frances Henderson: So that’s how the whole thing started. I adapted the film into a book, originally it was going to be a screenplay with actors, and that didn’t feel right to me. And I reached out to the Presleys, the parents of Levi, and they were interested in being a part of the film. So we just started this collaboration together, and I’m so grateful that they were able to put enough trust in me to help them tell their story in a way that felt very safe. And yeah, 12 years later, here we are.

MW: So did you have any conversations with John D’Agata about what you would do with his book?

L. Frances Henderson: I got the rights to adapt the book and, for a while, I was interested in kind of exploring with him his treatment of reality. And he’s actually gotten a lot of criticism about how much he tweaked specs. There was actually a supplemental book that came out, called The Lifespan of a Fact, which is him and the fact-checker at Harper’s, I believe, going back and forth. And John D’Agata’s defending his choice in words or his choice in tweaking numbers or how he tells a story out of order, non-chronologically, and then the fact-checker pushing back and saying, ‘Can you really do that? Is that really ethically right?’ And John D’Agata is defending his art. That became a Broadway show, starring Daniel Radcliffe, Bobby Cannavale, and Cherry Jones.

L. Frances Henderson: So I wanted to engage with him in the same way and just have this back and forth about how we understand things through art, and is that more truthful sometimes than understanding through numbers and computational analysis? But it started to speak to me in a very different way. One of the things that came up about halfway through my process was my own friends’ death. And before that, I had never really considered me being the voice-over narrator, or even incorporating my story at all, but the backstory of how I got to be in Las Vegas became the personal drive for the whole film. So yeah, that’s how it all came together.

Acting Out Your Own Life Story

MW: Was Levi the same individual that John D’Agata wrote about, who took his life? And what was it like going to his family and friends and having them revisit this tragedy?

L. Frances Henderson: It’s the same boy that John D’Agata wrote about. Levi had taken his life in 2002. John D’Agata took time to write this book and it came out in 2010. I came about in 2011. So it had been nine years since they had to face this grief. Of course, it never leaves you losing a child, especially in that way. It never leaves you. But I think, and I can relate to this with my own friend, engaging in the pain and engaging in the person that you love and talking about the person that you love, that helps with the healing. Because it almost is like you’ve found a different way of connecting with that person.

L. Frances Henderson: That was tricky, trying to navigate how to work with the Presleys and how to depict that time when there’s, like I described, this void of not knowing, and the discomfort of having to live within that unknowable space. And I wanted to show that time when they were really not grieving in the way that was helpful, and that they were really struggling. And so, there were certain ways that we worked together to have them express that, but without having to go back to that feeling.

L. Frances Henderson: And one of the ways that I came up with is like, just telling Gail to look out the window and kind of look at a spot and try not to blink her eyes for as long as possible. Or giving her the sense that I wanted her feeling to look like she had just woken up after having a long night of work and hadn’t had her coffee yet. Or Levi’s father, I wanted him to stand outside and grind his teeth a bit to show how much he was holding back his own emotions. So there were little things that I directed them to do that showed this kind of grief but in a safe way.

MW: Would you say that there’s an element of acting then, like a Robert Flaherty film or Robert Greene, like a hybrid documentary?

L. Frances Henderson: Documentary is kind of a false term, a false description of what it is. I mean, if people know they’re in front of the camera, they’re gonna act a different way. And so in a way, I’m trying to get them to act more natural and not know that they’re acting, but in fact, they are performing in a way. Gail, the mother, one time a new crew member came came in and Gail said, “Welcome to our movie!” She was excited to be part of a movie. And I treated her like an actor, and that she had people around her and I made sure she was well taken care of. And I think it’s interesting. I’m not too familiar with Robert Greene’s process but I imagine it’s the same way, where we’re engaging in this almost like — I wouldn’t call my work art therapy or theater therapy, but there’s a certain element to it. I think acting in your own story allows you to have a perspective and also engage with hard emotions, but in a very safe way.

The Reverence of Not Knowing

MW: Do you feel like you came to any realizations, or found a sense of closure, after making this film?

L. Frances Henderson: Humans are so funny. I mean, we’re just a funny species, where we think we can cheat the system and kind of know more than other beings can, but we can’t. So we can [try to] understand through science and through math and through all these different layers of knowing. But in the film, I don’t just stop there with the computational answers; I go to a psychic and ask her what she thinks. And ironically, or maybe not, depending on your belief, that psychic medium gives more satisfactory answers that are emotionally fulfilling and help with the healing process than any kind of statistics can provide. So, knowing is a gray space, and I think it’s a beautiful gray space. I think we need to learn how to embrace all different kinds of knowing and acknowledge the fact that none of us know, but we like to think that. There’s comfort and aspects of knowing.

MW: Yeah, I remember the realization that there isn’t someone in charge, and that nobody actually has the answers to everything, that they’re all just making it up as they go along.

L. Frances Henderson: I’m very thankful that I didn’t major in philosophy, although it’s a beautiful way of thinking. But it’s maddening, too, because they don’t have answers either.

MW: Between This Much I Know, your thesis film Elderly, and Lessons for the Living, you keep exploring death in interesting ways. Why is that?

L. Frances Henderson: It’s definitely a fascinating subject to me, purely because we don’t know what comes after it, if anything. And also, to face your own mortality is — I hesitate to say humbling, because it’s deeper than that. But it allows us to have perspective on what we’re doing right here and right now, and the fact that we are evolving and changing, and we will eventually cease to exist, and there’s some kind of reverence that I find within knowing that and embracing that. And so that’s, I think, ultimately what my fascination and interest is, is that kind of reverence.

From Oscilloscope Laboratories, This Much We Know had its world premiere at the 2022 Camden International Film Festival, and is due to be released theatrically in NYC on Friday, November 10th and will open in LA on Wednesday, November 15th. You can learn more at its website here.

This story originally appeared on Movieweb