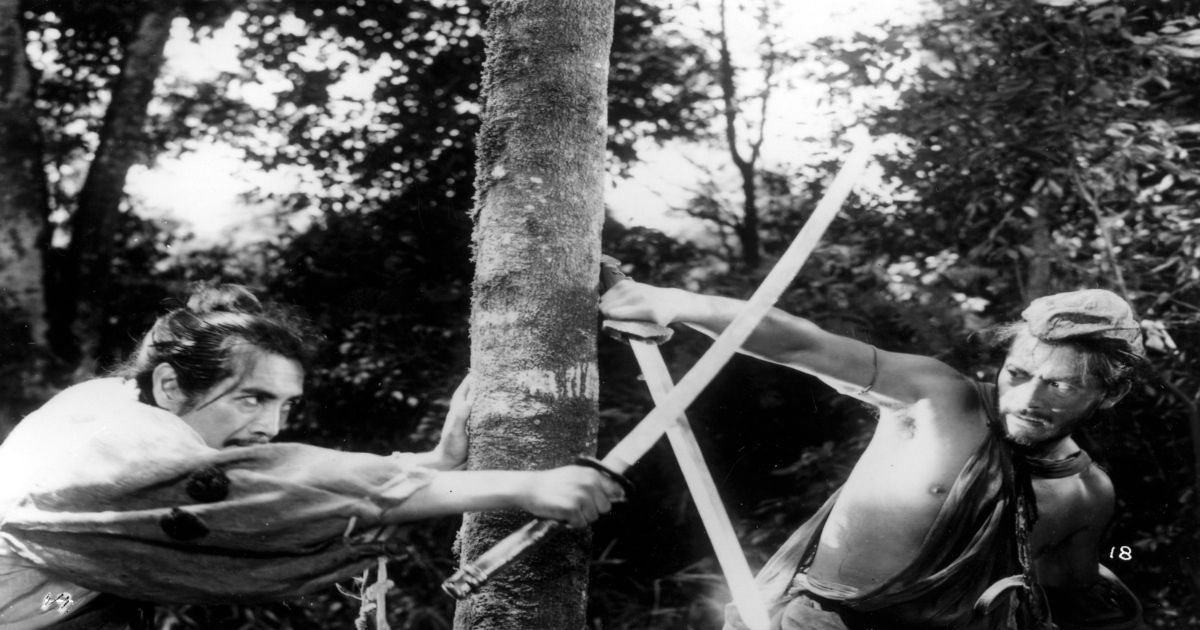

The story goes like this: a bandit lures a samurai off a beaten mountainside path to admire a cache of ancient swords. But he tricked the samurai, tying him up to a tree and seducing his wife. Then, he untied the samurai and battled him in a one-on-one swordfight to the death. The bandit came out on top, but when he turned to the samurai’s wife, she had vanished. And thus, he went about his day. At least, that’s one version of the events.

Directed by Akira Kurosawa from a script he co-wrote with Shinobu Hashimoto, Rashomon (1950) features four eyewitnesses each with their own perspective on the events that triggered its plot: the murder of a samurai. Obviously, this project is where the story method or phenomenon at hand found its origin. The Rashomon Effect can essentially be described as any given situation where groups of eyewitness give varying and often-times conflicting testimonies to the same event.

They can never agree on the legitimate outcome, and often times, they shape their own, respective story to paint themselves in the most ideal possible light. For an example of the effect, there’s no better story to cite than the primary source itself by the famous Japanese director: Kurosawa’s Rashomon.

The Origin — Rashomon by Akira Kurosawa

In the city of Kyoto during the Heian era, a priest and a woodcutter shelter underneath the Rashōmon city gate as rain deluges around them. A commoner joins them, staying dry himself, and they regale one another with the story of a two-part crime that had recently taken place: the murder of a samurai and the raping of his wife.

The notorious bandit named Tajōmaru had already staked his claim, saying he fought honorably with The Samurai, and never truly assaulted The Wife, but instead seduced her. The Samurai gives an alternate telling of the event. Already dead, The Samurai relays his version of events via a medium, a Shinto psychic.

He says Tajōmaru raped his wife and that, despite this, she wanted to leave with Tajōmaru. Thus, Tajōmaru gave The Samurai a choice: let her go, or kill her. But she had already fled, and once Tajōmaru departed as well, The Samurai plunged The Wife’s dagger into his chest, committing suicide. Of course, her testimony disagrees.

The Wife says Tajōmaru assaulted her and left. Then, she fainted upon seeing her husband’s stone-cold reaction. When she came to, the dagger was plunged in his chest. Not entirely different, but it shows her in a far more faithful light. Then, there’s The Woodcutter, named Kikori.

He claims to have found the body of a murdered samurai three days earlier. It’s eventually revealed that Kikori saw a fight take place, that the two combatants came to rather clumsy blows, and that The Samurai was actually killed with a sword, not a dagger. This hardly impacts Kikori’s overall standing, but each story nonetheless has an effect on the film’s story itself.

The Rashomon Effect — What Does It Mean?

The term permeates throughout a wide range of mediums, from psychology and legal studies to sociology and literature. But as a storytelling device, The Rashomon Effect sets up tension and confusion for each subsequent scene. To best explain its overall impact on audiences, reference the parable of the blind men and an elephant.

One day, a group of blind men stumble upon an elephant. They had never encountered an elephant before this day, and wanted to know what one looked like. Thus, each blind man grabbed a different body part of the elephant, then described the attributes thereof to paint a grand, singular picture.

They each grab one part of the elephant such as the tusk or the tail. But when one blind man describes their part as a wall, another a snake, followed by a tree, a spear, a fan, or a rope, well — things get confusing for everyone involved. This is essentially The Rashomon Effect. They suspect the next blind man over to be dishonest in what they felt, with the general message being that humans tend to claim something as the truth based on their experiences of limitations and subjectivity. But they then turn around and ignore the similarly limited and subjective experience of the next person.

With reference to The Bandit in Rashomon, The Priest notes that men lie, even to themselves, because they are weak. For The Samurai, it’s at one point noted that dead men have no reason to lie. Meanwhile, The Commoner notes regarding The Wife that women use their tears to hide lies, and end up fooling themselves. Each description adds new meaning to the subjectivity of each experience, providing a sort of subconscious motive for the parties involved. For other examples, there are of course dozens of films to check out across the medium.

Its Use Throughout Film

Since the original film was released at the turn of the 1950s, filmmakers across the world have utilized this phenomenon for their films. As a storytelling device, it can be found in lesser-known titles such as Go (1999), a crime comedy by Doug Liman, along with Elephant (2003), a psychological drama directed by Gus Van Sant. There’s also Talvar (2015), a Hindi-language thriller film, which arguably uses the device to perfection more so than anything that came after its progenitor.

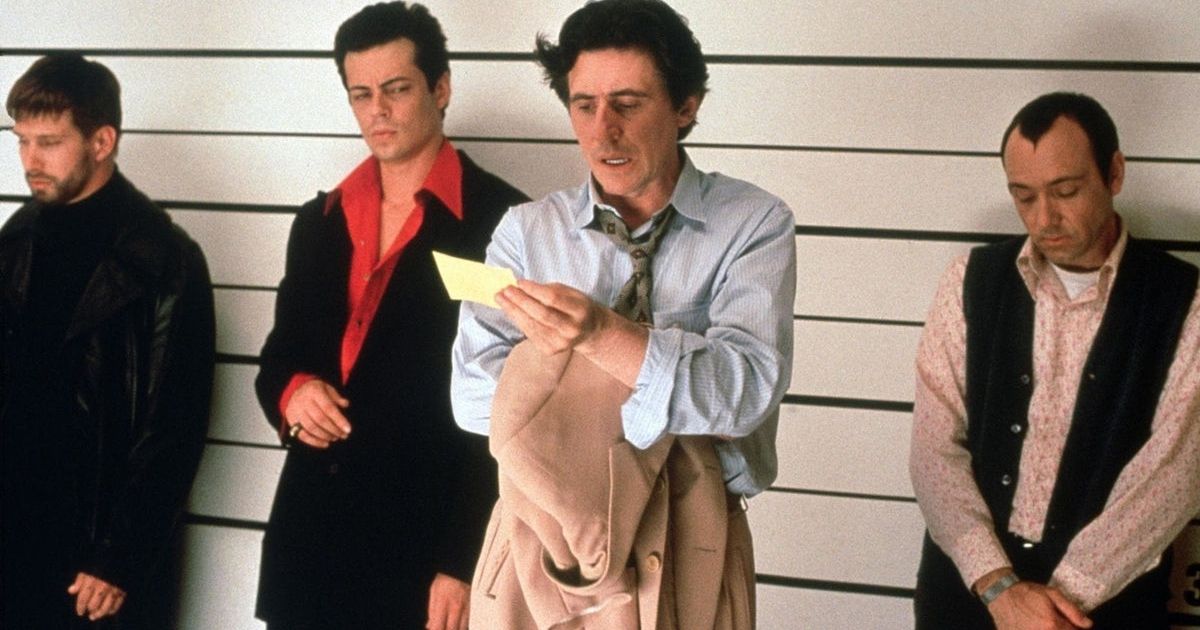

The two most famous films to use The Rashomon Effect — aside from the Kurosawa project itself — would be The Usual Suspects (1995) by Bryan Singer and Gone Girl (2014) by David Fincher. Those are two famous, neo-noir mystery movies of more modern times, with both going down among the most popular and revered of their respective years. And they both used The Rashomon Effect to achieve brilliant results of tension, conflict, and storytelling in general.

But in the end, nothing will ever do it better than the original. The best example of The Rashomon Effect is obviously the Kurosawa title from which its title is derived. And oddly enough, Rashomon actually received modest reviews from Japanese critics upon release. They were rather confused upon learning that the film reached such acclaim overseas. But in hindsight, Kurosawa’s masterful project Rashomon should go down as a masterpiece of cinema if not for the widespread use of this phenomenon alone.

This story originally appeared on Movieweb