A stainless steel safety net sits below the sidewalk on the Golden Gate Bridge on Jan. 5, 2024, to discourage people from jumping and to catch those who do.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

hide caption

toggle caption

Beth LaBerge/KQED

A stainless steel safety net sits below the sidewalk on the Golden Gate Bridge on Jan. 5, 2024, to discourage people from jumping and to catch those who do.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

Michael James Bishop left his apartment on Pine Street in San Francisco around 8:45 a.m. on March 28, 2011. He drove his gray Honda to the parking lot at the Golden Gate Bridge. He scrawled a detailed suicide note and laid it on his car seat.

The sun was shining for the first time in weeks. It was 51 degrees outside. The 28-year-old with brown curly hair, green eyes and silver-rimmed glasses stepped out of his car and walked to the middle of the bridge. Then Bishop turned toward San Francisco and leapt.

“A motorist who was driving by happened to see my son go over the rail,” says Kay James, Bishop’s mother.

When James received a call from the sheriff she was shocked. “That he would kill himself – never entered my mind. He was so sweet. He was a very gentle young man.”

Her son had a lot going for him. He was in a relationship with a woman he adored. He played the violin in an orchestra. He was on tap to start a new job at an environmental fund. In fact, that fatal day was supposed to be his first day at work.

But he’d struggled with depression in the past, and he was overwhelmed. The suicide note said, “I’m so sorry. I just can’t handle things.”

Kay James sits in her home in Moraga on Jan. 9, 2024. Her son Michael Bishop died jumping off of the Golden Gate Bridge in 2011.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

hide caption

toggle caption

Beth LaBerge/KQED

Kay James sits in her home in Moraga on Jan. 9, 2024. Her son Michael Bishop died jumping off of the Golden Gate Bridge in 2011.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

“I just felt so devastated,” says James. “You feel like your world is coming to an end.”

Her son’s computer history revealed that he had researched the Golden Gate Bridge. It’s an iconic landmark, but it’s also a lethal one. About 2,000 people are estimated to have plunged to their death since 1937 – an average of about two people a month. Suicide prevention advocates have pushed for a deterrent for decades.

Now, after years of meetings and delays, their dreams are a reality.

On a crisp clear day in early January, Denis Mulligan, the general manager for the organization that oversees the bridge, leans out over the guardrail and points down at reddish orange beams connecting stainless steel silver net that looks like chain link fencing. It’s suspended 20 feet below the pedestrian walkway. Mulligan says it will hurt if someone jumps – it’s the same marine grade material used to hold the mast of sailboats in place.

“It’s something that’s made for this harsh environment,” he says. “It is not soft. It is not springy. It’s like a giant cheese grater.”

The net extends 1.7 miles down both the west and east sides of the bridge. Mulligan says it’s 95 percent complete.

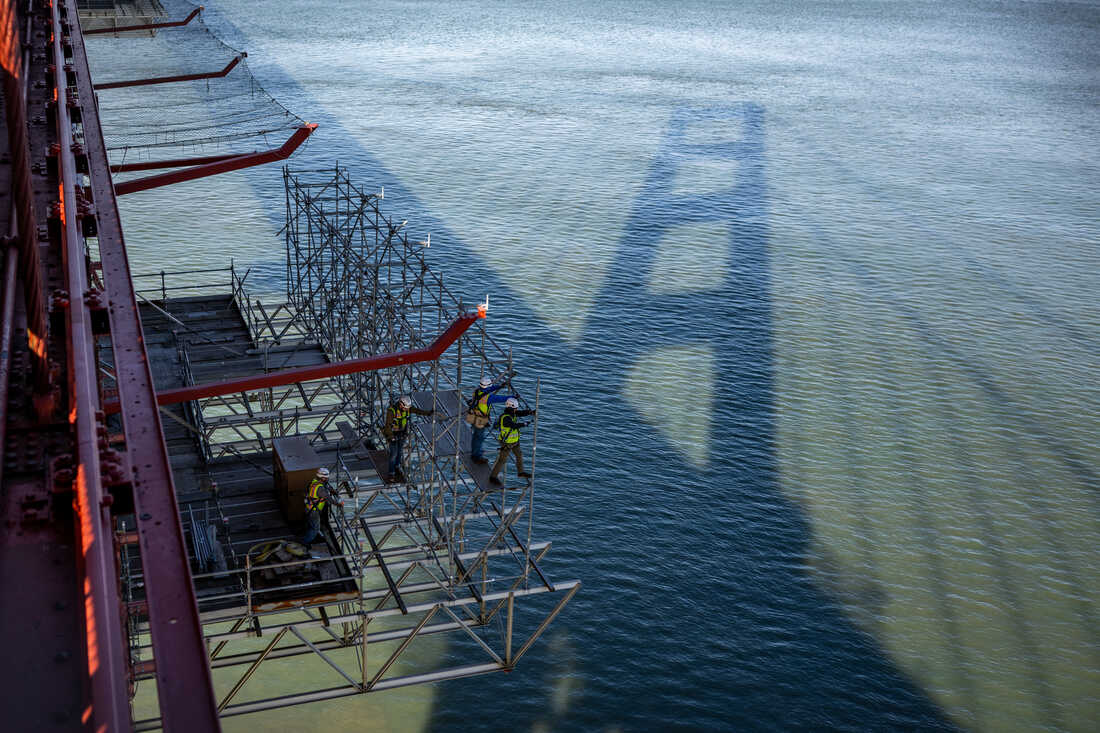

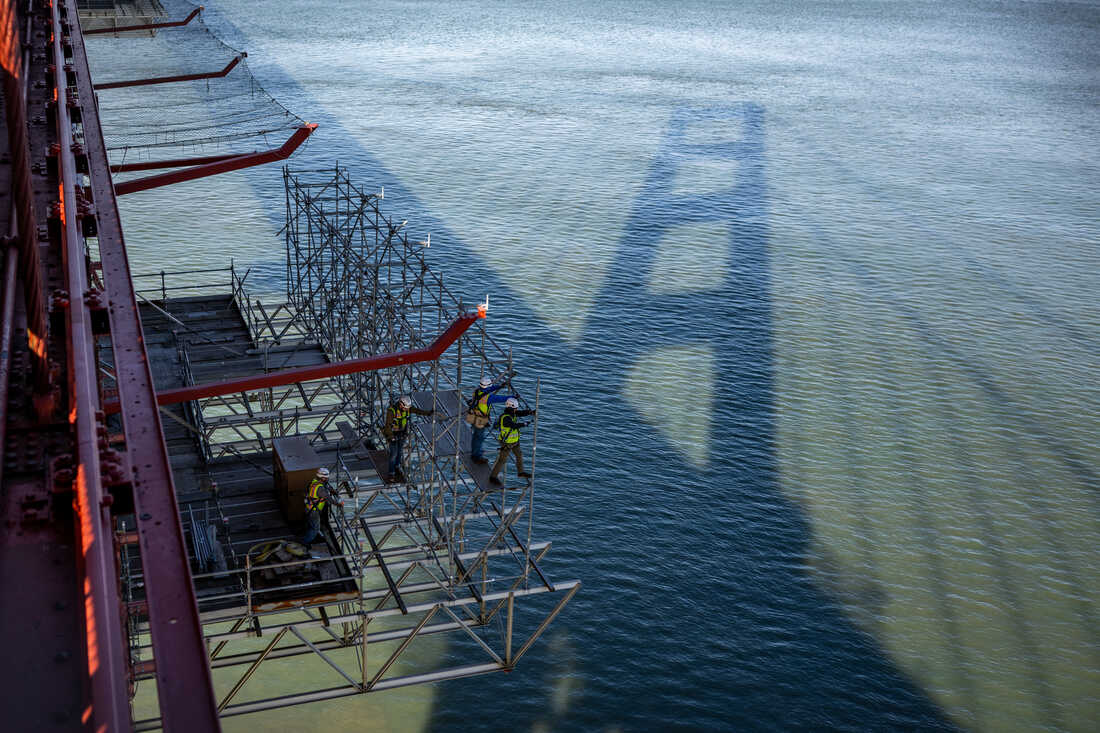

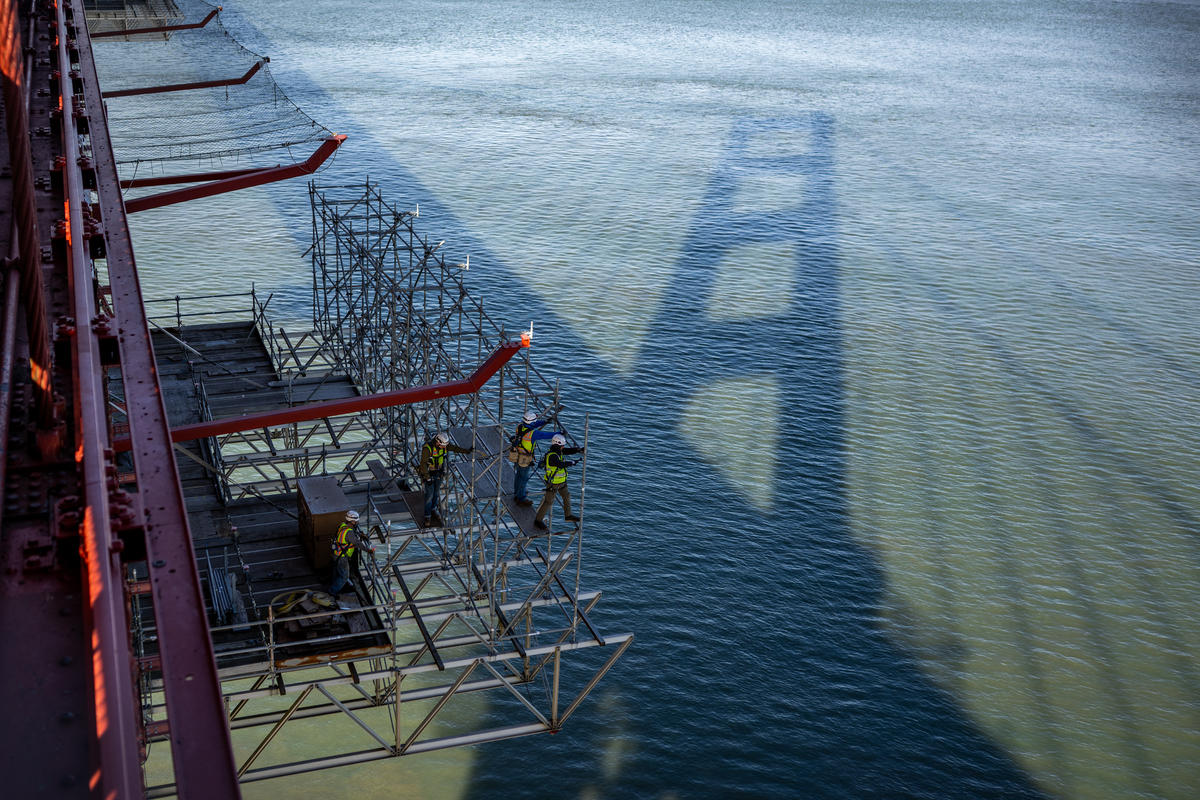

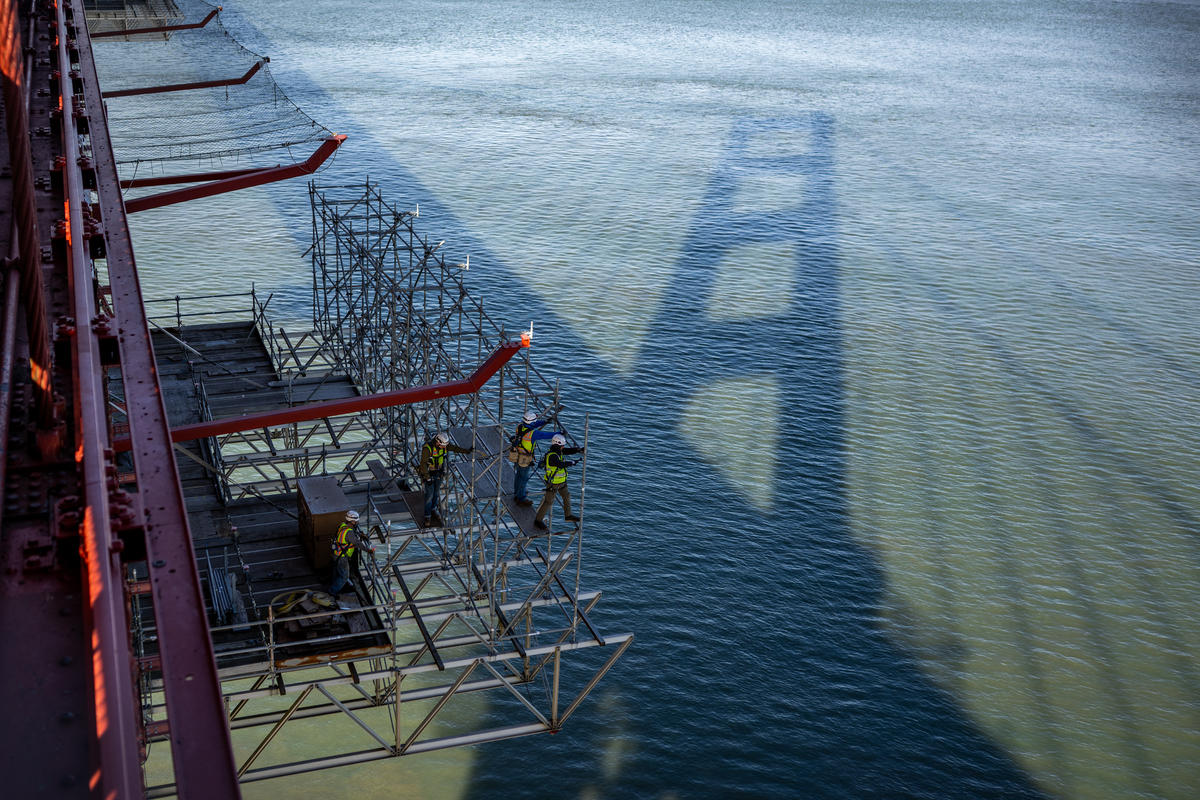

Workers install a stainless steel safety net below the sidewalk on the Golden Gate Bridge on Jan. 8, 2024. The net is designed to discourage people from jumping and to catch those who do.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

hide caption

toggle caption

Beth LaBerge/KQED

Workers install a stainless steel safety net below the sidewalk on the Golden Gate Bridge on Jan. 8, 2024. The net is designed to discourage people from jumping and to catch those who do.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

“It’s a massive undertaking,” says Mulligan. “We have over seven football fields worth of netting stretched out on the Golden Gate Bridge.”

None of which you can see from the roadway. Mulligan says the public did not want the net to detract from the bridge’s beauty; it was a primary point of contention during the design phase.

“Public comments from families who had lost a loved one said, ‘If you had built something, my child would still be alive.’ While others said, ‘Don’t you dare change how the bridge looks,'” says Mulligan.

Finally, he says, the Golden Gate Bridge board concluded that they would build something if someone else paid for it. Federal highway grants covered the $224 million cost to construct the suicide barrier.

The stunning location is commonly thought to be one reason why people jump from the magnificent structure into the crashing waves below. But mental health experts say the view is not the draw, instead, accessibility and familiarity are the primary drivers.

“People who have attempted suicide will say that they felt more comfortable with a given method,” says Matthew Nock, professor and chair of the Department of Psychology at Harvard University. “They are comfortable with jumping off a bridge, whereas they were afraid to hang themselves, or take an overdose or they didn’t have access to a firearm.”

A flower cutting lays on a stainless steel safety net below the sidewalk on the Golden Gate Bridge on Jan. 8, 2024, designed to discourage people from jumping and to catch those who do.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

hide caption

toggle caption

Beth LaBerge/KQED

A flower cutting lays on a stainless steel safety net below the sidewalk on the Golden Gate Bridge on Jan. 8, 2024, designed to discourage people from jumping and to catch those who do.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

“The Golden Gate Bridge is the perfect target,” says Mel Blaustein, a psychiatrist at St. Mary’s Medical Center in San Francisco who has researched bridge suicides for many years. “There’s a parking lot, and there’s a bus that takes you there. It’s easy and fast. And when I say fast, it takes four seconds to hit the water.”

One jumper reportedly left a note on the bridge reading, “Why do you make it so easy?”

The net is intended to make people rethink their decision. Some opponents to the project argued that people would just go somewhere else to kill themselves. But the research does not illustrate that. A U.C. Berkeley study followed people after they had been stopped on the bridge during a suicide attempt. The vast majority did not go on to die by suicide somewhere else, even years later.

“There’s pretty universal agreement that if we know that people are going to try and kill themselves by jumping off a specific bridge then it’s ethical, reasonable, and clinically wise to put up a netting and prevent those suicides because some percentage of folks who are deterred are never going to try and kill themselves again,” says Nock.

Photos of Kay James and her son Michael Bishop hang on the wall of her home in Moraga on Jan. 9, 2024. Bishop died jumping off of the Golden Gate Bridge in 2011.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

hide caption

toggle caption

Beth LaBerge/KQED

Photos of Kay James and her son Michael Bishop hang on the wall of her home in Moraga on Jan. 9, 2024. Bishop died jumping off of the Golden Gate Bridge in 2011.

Beth LaBerge/KQED

Kay James wished a net would have deterred her son Michael. She has talked to people who survived suicide attempts at the Golden Gate Bridge. They told her they regretted their decision the minute they let go of the guardrail.

“That’s really hard for me because I think, ‘If only he would have had a second chance. And of course, with a net, you definitely have a second chance.'”

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide or is in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

This story originally appeared on NPR