While stocks dither in the new year, a dramatic rally has been under way in one corner of the commodity market that industry watchers expect to just keep going.

The spot price for uranium, vital for fueling nuclear reactors, climbed to just over $103/pound on Monday, a level not seen since 2007, according to a chart from Numerco, a U.K.-based spot price for uranium. That follows a roughly 90% price gain for the metal in 2023 in a market that has struggled to keep up with fresh demand.

“The uranium market is undergoing a major speculative investment rush with ETF’s holding physical stocks continuing to suck in stocks, thereby adding to the tightness being driven by the prospect of rising demand in the coming years, and a rush of buying of from utilities who have become lazy with hedging following years of low prices,” said Ole Hansen, head of commodity strategy at Saxo Bank.

Spot price for uranium ore concentrate, commonly referred to as U3O8.

Numerco

Uranium prices initially shot past $100/pound last Friday after Kazakhstan’s state uranium company said it may not meet production goals. NAC Kazatomprom, the world’s biggest producer, said it was struggling to source sulfuric acid used in extracting the metal and seeing construction delays at new deposit discovery sites. It was targeting 2024 production volume at 90% of what permits allow.

That adds to production downgrades in 2023 from Canadian uranium miner Cameco

CCO,

and French miner Orano’s operation in Niger, equity analysts Chris Drew and Christopher LaFemina, said in a note on Monday.

In their view, uranium prices are on track to bust past the June 2007 all-time high of $136/lb. “Furthermore, with term contracting volumes barely at replacement levels at a time when spot pricing is through US$100/lb, the setup for term pricing remains bullish,” said the analysts. “Major producers remain short pounds.”

That tight market has been amplified by “ongoing” buying from Sprott Physical Uranium Trust

SRUUF

or SPUT, the world’s biggest physical uranium fund, and Yellow Cake

YCA,

an investment vehicle that makes bets on uranium, said the Jefferies analysts, who added: “The squeeze is on.”

Australian miners Paladin Energy

PDN,

Boss Energy

BOE,

and Deep Yellow Limited

DYL,

remain their preferred exposures, even as the Jefferies analysts admit valuations remain “elevated.” Those miners jumped around 7%, 9% and 11%, respectively, on Monday, and have gained 30% each for the year so far.

Shares of Yellow Cake, up 15% so far this year, rose 2.6% in London on Monday.

Read: Why the rally in uranium that lifted prices to a 15-year high may not be over

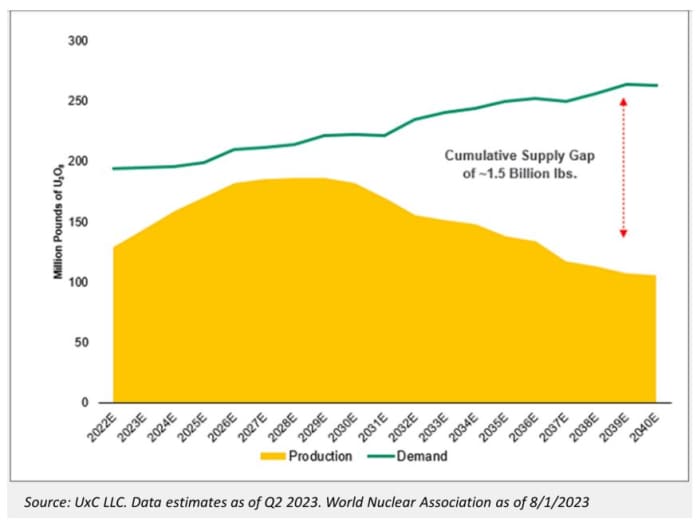

In an interview that published last week with Macro Voices, Uranium Insider founder and newsletter editor Justin Huhn laid out the basic investment case for uranium via the below chart:

It shows “actual expected mined pounds out of the ground on an annual basis compared with the actual burn up rate of the global nuclear reactor fleet. And you can see that we basically remain at a deficit even with expected peak production toward the end of the decade,” Huhn said.

Since an abundance of supply in the 1980s, uranium has been in shortfall, with two bull markets in that period and the mid 2000s. “The difference now is that there’s very little secondary supply to balance that shortfall of production,” he said.

Secondary supply refers to inventory held by governments and utilities, which stood at around 30 million pounds plus even during the “rip roaring bull market” of the mid 2000s, he said.

Fast forward and just 15 million pounds of secondary supply exist today, with anyone who could be selling that inventory not doing so, while the last 18 months has seen China aggressively buying, he said.

So regardless of where the uranium price is, “pretty much any mine in the world can be making money,” yet a supply shortfall will persist and it will be many years before big new mines will come online, said Huhn.

Another stressor for the market is a looming ban on Russian fuel services by the U.S., with the Senate just a vote away from pushing that through. Ultimately, Russia could retaliate with a ban on exports rather than accept a phase out by 2028 in that legislation. “An immediate ban would have more serious consequences, likely squeezing prices throughout the nuclear fuel chain,” said Drew and LaFemina.

This story originally appeared on Marketwatch