When the pain kicked in again in February, Lahisha Marquez-Soto held off on going to the hospital for days, until she was struggling to walk out of her college dorm in Carson.

Eight days into her stay at MLK Community Hospital, doctors knew she needed another facility. She needed a medical procedure that would allow doctors to peer inside her digestive tract and perform a biopsy to find out what was wrong with her pancreas. That was something that the small hospital in South Los Angeles could not do.

But week after week, the 20-year-old lay waiting in frustration. Stranded in her hospital bed, she missed college classes, birthday celebrations, a scheduled visit with her siblings in foster care. She read novels, watched HGTV and tried not to think about what she was missing.

“It messes with you mentally,” she said. “You’re just stuck in a room.”

Lahisha Marquez-Soto is a patient inside MLK Community Hospital. Eight days into her stay, doctors knew she needed to go to another hospital.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

Marquez-Soto was at the mercy of a haphazard process that plays out through phone calls and faxes, as smaller hospitals try to find help for patients who need medical procedures that those hospitals cannot provide.

Hospitals are generally required under federal law to accept transfer patients suffering from medical emergencies if the facilities have space and capability; but federal officials said that does not obligate them to accept those like Marquez-Soto, who have already been admitted to a hospital. Hospital employees armed with phone lists often need to call, and call, and call until they can secure a spot. One MLK staffer likened it to throwing spaghetti against the wall to see if it sticks.

“This is a mess right now.”

— Dr. Michael Gertz, president-elect of the California chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians

Delays in transfers can put people at higher risk of complications and derail day-to-day life for patients. Hospital officials from around the state say that transferring patients has generally gotten harder as many health facilities struggle with staffing, which cramps hospital capacity to accept transfers. Some said that in Southern California, demand for ambulances is also exacerbating delays.

“The general public has no idea of what it takes to transfer a patient,” said Dr. Ferdinand Panoussi, medical director of Horizon Multicare, which provides hospitalist services for Antelope Valley Medical Center in Lancaster. “They think that it’s just as easy as picking up the phone.”

At Antelope Valley Medical Center, some patients who need to be transferred have grown so tired of waiting that they have decided to leave against medical advice, hoping to show up and get in through the emergency department at another facility, Panoussi said.

Ernesto Chavez, a patient at MLK Community Hospital, is transferred to Keck Hospital.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

“This is a mess right now,” even for emergency patients, said Dr. Michael Gertz, president-elect of the California chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians. He also works at Antelope Valley Medical Center. Even if another facility accepts an emergency patient, “we’re often holding that patient for 12 to 24 hours until we can actually get an ambulance that is willing to take them.”

Gertz said the state does not collect data on such delays in transfers, making it difficult to quantify the problem. MLK hospital officials said their data show that over roughly a year, patients admitted to the hospital had an average wait of more than three days after their transfer had been requested — and that average waits have been longer for those covered by Medi-Cal, the California Medicaid program.

Marquez-Soto, who has Medi-Cal coverage, said she had held off on going to MLK because she expected to end up waiting. In fall, she waited to be transferred to another hospital for the same kind of procedure, but it took so long that she was discharged and told to follow up for an appointment.

She hadn’t gotten that procedure before the pain sent her back to the hospital.

“It makes me feel very helpless,” said Dr. Maita Kuvhenguhwa, who treated Marquez-Soto at MLK. “Even when we’re doing our best and putting in a ton of work, if the patient can’t get to where they need to go, then we’re not helping them.”

::

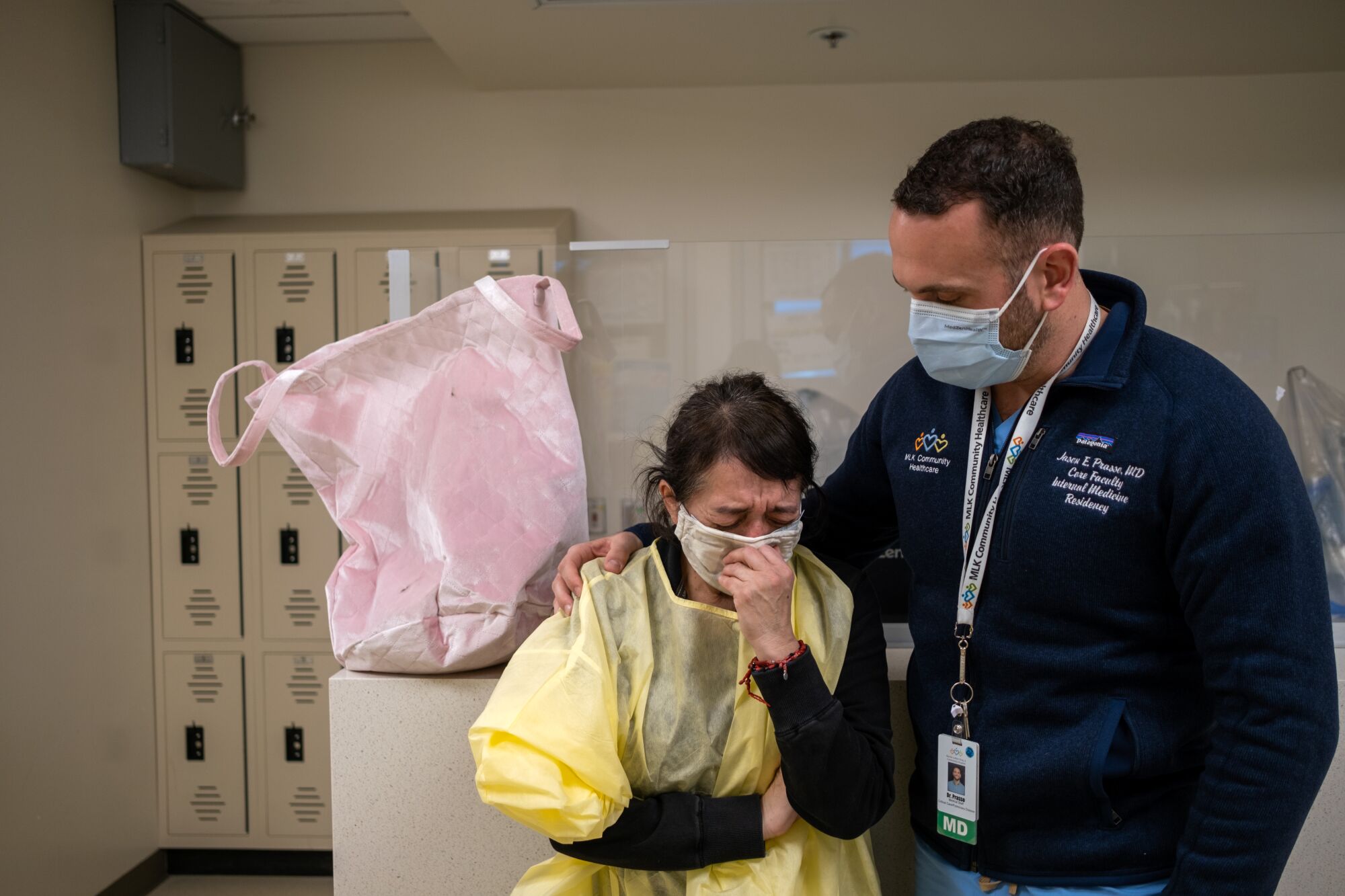

Elena Padilla, left, speaks with Dr. Jason Prasso inside the intensive-care unit at MLK Community Hospital. Elena’s brother needs to be transferred to a different facility for a medical procedure.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

Decades ago, federal lawmakers passed the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act to prevent emergency rooms from refusing to treat uninsured patients or “dumping” them on other hospitals. The law requires emergency rooms to treat people who come in suffering from a medical emergency.

If a transfer is medically appropriate, it also requires hospitals to accept people with emergency conditions from another hospital if they have space and “specialized capabilities” to help those patients, as long as the transfer is medically appropriate. But nothing in federal law requires a hospital to accept a transfer patient who has been admitted to another hospital as an inpatient, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

“Every day a little bit of my heart is chipped.”

— La Shaunta Harris, manager of emergency department care management and transitional care at MLK

When patients need a medical procedure that their hospital does not offer, but are not in an emergency state, “there’s not a whole lot of guidelines to direct hospitals in terms of how to manage those transfer requests,” said Dr. Stephanie K. Mueller, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

The process “is in no way systematically thought out,” and bias can creep in when clear standards are lacking, said Dr. Evan Shannon, an assistant professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. He and Mueller found in one study that Black patients were less likely to be transferred out of hospitals than white patients, as measured among Medicare inpatients with medical conditions that typically benefit from transfer.

Another study found that once they were admitted to the hospital, uninsured patients were less likely to be transferred out than those with private insurance. Insurance coverage can decide where a patient goes or slow the process, community hospital officials told University of Michigan researchers.

Nurse Sophea Soth, right, keeps an eye on patient Ernesto Chavez as EMTs wheel him down the hall at MLK Community Hospital.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

La Shaunta Harris, manager of emergency department care management and transitional care at MLK, said that as she tried to transfer an inpatient, one hospital told her that “there’s only so much charity we have.” That hits her especially hard because she is from this community, she said.

“Every day,” Harris said, “a little bit of my heart is chipped.”

Under federal law, nothing prohibits hospitals from turning down an inpatient transfer because of the insurance coverage of the patient, a CMS spokesperson said. The problem spilled into public view during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the Wall Street Journal obtained emails indicating that some California hospitals refused or delayed accepting COVID patients from overrun hospitals because of their insurance status.

Doctors said some patients suffered lung damage and other complications because of delays, the newspaper reported.

The back-and-forth over relocating patients usually happens out of public view, but the emails became public because California had hired a contractor to help relieve the pressure on overwhelmed hospitals earlier in the pandemic. The California Emergency Medical Services Authority also steps in to help transfer patients during disasters such as wildfires when hospitals must be evacuated, but does not get involved with transfers on a day-to-day basis.

Many hospital systems have set up their own centers to manage requests to transfer patients into their facilities, including the hospitals run by Los Angeles County. Some hospitals have agreements with others about accepting patients. But there is no central clearinghouse to check every nearby hospital for suitable beds.

Gertz argued that COVID-19 “was a crisis, but now we’re in a permanent crisis. There’s going to have to be a government intervention.”

::

At MLK Community Hospital, Lourdes Beltrán strategized before her computer monitor, trying to figure out how to free Marquez-Soto from her misery. She pulled out a weathered piece of paper from a folder — a printed list of phone numbers jotted with handwritten notes — and dialed.

Lahisha Marquez-Soto begins to cry as she lies in a hospital bed at MLK Community Hospital.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

“Good afternoon. My name is Lourdes. I’m one of the case managers here at Martin Luther King Community Hospital,” she said when someone answered at a medical center, explaining that she was following up on a transfer request.

She listened, her pencil hovering over a printed summary of the case, as someone at the medical center explained they were still awaiting paperwork. After she hung up, she dialed up the health plan to ask if it could push things along. “We’re still trying to move that patient,” Beltrán told them.

Beltrán glanced at the row of names on her screen, many tagged with a red bar labeled “Exceeded” because they had stayed longer than expected. The health plan said it already sent the needed paperwork, so she dialed the medical center again. It had taken nearly half an hour, she said, to get a “non-answer.”

“I want to cry and scream, but I have to put up with it.”

— Ernesto Chavez, MLK patient

Beltrán then turned her attention to Ernesto Chavez, a 65-year-old man who had arrived at the hospital more than a week earlier after enduring many days of vomiting. He had lost 10 pounds in two weeks, he told them.

The problem was a giant obstruction in his small intestine, but “we can’t do anything about it here,” said Dr. Tiffany Maggi-Maidinetti. “We don’t have the surgical specialists to remove or biopsy it safely.”

If it turned out to be cancer, Maggi-Maidinetti worried, a holdup could delay the care he needed. And if the thing inside him grew, she feared it could damage his intestine.

It had been three days since MLK issued a transfer order, and Beltrán had no luck. She dialed another number and punched in digits on an automated menu before someone picked up and she rattled off his medical details. Then came the question of health insurance: Chavez was in the process of getting Medi-Cal coverage.

Ernesto Chavez, 65, is in a considerable amount of pain as he waits to be transferred to a different hospital.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

Chavez is in a considerable amount of pain, hospitals are generally required under federal law to accept transfer patients suffering from medical emergencies.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

In a dimly lit room, Chavez lay with an arm draped over his forehead, grimacing with pain. He strained to speak, his throat painfully dry. The patient, who had been working as a carpenter, had spent days at home, unable to eat or drink anything without vomiting, before his co-workers took him to the emergency room.

“I want to cry and scream,” he said faintly in Spanish from his hospital bed. “But I have to put up with it.”

One week later, Beltrán said Chavez had been approved for Medi-Cal and another hospital had agreed to accept him. But they were still waiting on an available bed. So Chavez remained in limbo. Doctors at MLK were trying to quell his pain and nausea, keep him hydrated, and stave off any complications or infections from the tubes threading his body, including one snaking from his nasal passages to his stomach to clear out bile.

“We’re at a standstill, basically,” Maggi-Maidinetti said.

That evening, Chavez was finally transferred. Chavez, reached weeks later, said he had undergone an operation there and that he was finally able to eat and drink again without vomiting.

Before he was transferred, “I felt desperate,” he said.

::

Transferring patients has long preoccupied smaller community hospitals because their patients may need medical interventions that they do not offer themselves. But getting patients where they need to be has become a concern for hospitals of all kinds as they grapple with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Elena Padilla visits her brother Juan Carlos Flores Esquivel at MLK Community Hospital.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

People have returned to hospitals after years of delaying care, but a staffing crunch has limited the number of beds available, hospital officials say. Medical centers have lamented that because nursing facilities are also short on staff, hospitals cannot discharge patients who no longer need a hospital bed but still need nursing care. That ties up beds in the hospital, gumming up the usual flow of patients from the emergency department into inpatient beds.

UC Davis Medical Center said it accepted more than 7,600 transfer requests in a little over a year — but turned down more than 9,900 due to limited capacity. And it too is struggling to move patients to other, less specialized hospitals once they can be safely cared for elsewhere.

“We run over 100% occupancy essentially every day of the week,” said Dr. J. Douglas Kirk, chief medical officer. “We absolutely have to get those patients out of the hospital because we have to produce that bed for the next patient who needs it.”

And “moving Medi-Cal patients typically is more sluggish than the commercially insured patients,” Kirk said.

Statewide data on median lengths of hospital stays show that Medi-Cal inpatients spent one day longer before transferring to another hospital, compared with transfer patients who have private insurance. At MLK, the average wait for a transfer was more than 50% longer for Medi-Cal inpatients than those with other coverage, according to figures provided by hospital officials.

Ambulance availability can also delay transfers, hospital officials said. Antelope Valley Medical Center Chief Executive Edward Mirzabegian said he has grown so frustrated with the waits that he is trying to create an ambulance company dedicated to his facility at an annual cost of more than $2 million. The Los Angeles County Ambulance Assn. faulted low reimbursements for ambulance providers to transport Medi-Cal patients, especially those not suffering a medical emergency.

“Very few people are willing to accept reimbursement rates that low, so there’s a limited pool of contractors that serve this patient population,” association president Chad Druten said. Last fall, American Medical Response said it would stop providing nonemergency transport in Los Angeles County, blaming low rates under Medi-Cal.

In January, MLK hospital officials were so worried about how long one patient had lingered there that the chief executive, Dr. Elaine Batchlor, got on the phone herself to try to find him a bed at another hospital. Because of its small size, MLK doesn’t offer cardiothoracic surgery, which physicians feared he needed.

“I’m doing my best, but I can’t do any more than what I can do here.”

— Dr. Eriko Masuda, an infectious disease physician at MLK

As he waited for a transfer, “he just sat here and sat here,” growing sicker and more lethargic, said Dr. Eriko Masuda, an infectious disease physician at MLK.

The man was suffering from a bacterial infection that his blood was ferrying throughout his body, showering the infection to his brain and elsewhere, Masuda said. As the weeks passed, the man suffered kidney failure and needed dialysis. His family members asked Masuda when he could leave. She had no answer.

“I’m doing my best, but I can’t do any more than what I can do here,” Masuda recounted.

Batchlor called physicians together to figure out what else they could do to help him transfer, and staff worked to upgrade his insurance coverage. Three weeks after MLK started trying to transfer him, the patient was finally taken to another medical center for heart surgery, and he survived.

Others in L.A. County have not been as lucky: Gertz wrote that in one case, a 45-year-old man who suffered a sudden, agonizing headache had been taken by his family to a San Gabriel hospital, where he was diagnosed with a ruptured aneurysm.

Because the hospital did not offer neurosurgery, it hustled to transfer him elsewhere, but arranging for transportation took so long that the man ended up in a vegetative state and was taken off life support, Gertz wrote to a Los Angeles County supervisor.

“Had the family taken him to the other hospital,” Gertz wrote, “he would have likely survived.”

Marquez-Soto was transferred to UCLA one month after MLK started trying to move her. There, she said, she was told her pancreas was too inflamed to move forward with the procedure that would have examined her digestive tract.

But doctors there spotted a rash and ended up diagnosing Marquez-Soto with a rare inflammatory disease that could be treated with an infusion of antibodies, she said. Finally, she started feeling better.

Times staff writers Sandhya Kambhampati and Hanna Sender contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared on LA Times