The swing shift is about to start at a plant that is about to close. Late winter sunlight casts long shadows from workers crossing the parking lot, where stray cats skulk among the cars.

Only two weeks left, and the routine is unchanged: clocking in at 5 p.m., heading to the locker room, trading street clothes for work wear. If anyone feels sadness or loss, no one shows it. They have a newspaper to put out.

“We’re trying to do this with a little class and dignity,” said shift supervisor Kal Hamalainen.

Sixteen months ago, they were told that the Los Angeles Times, their employer, would outsource the printing of the paper and that the Olympic printing plant, once a crown jewel in a vast media empire, would shut down sometime in 2024.

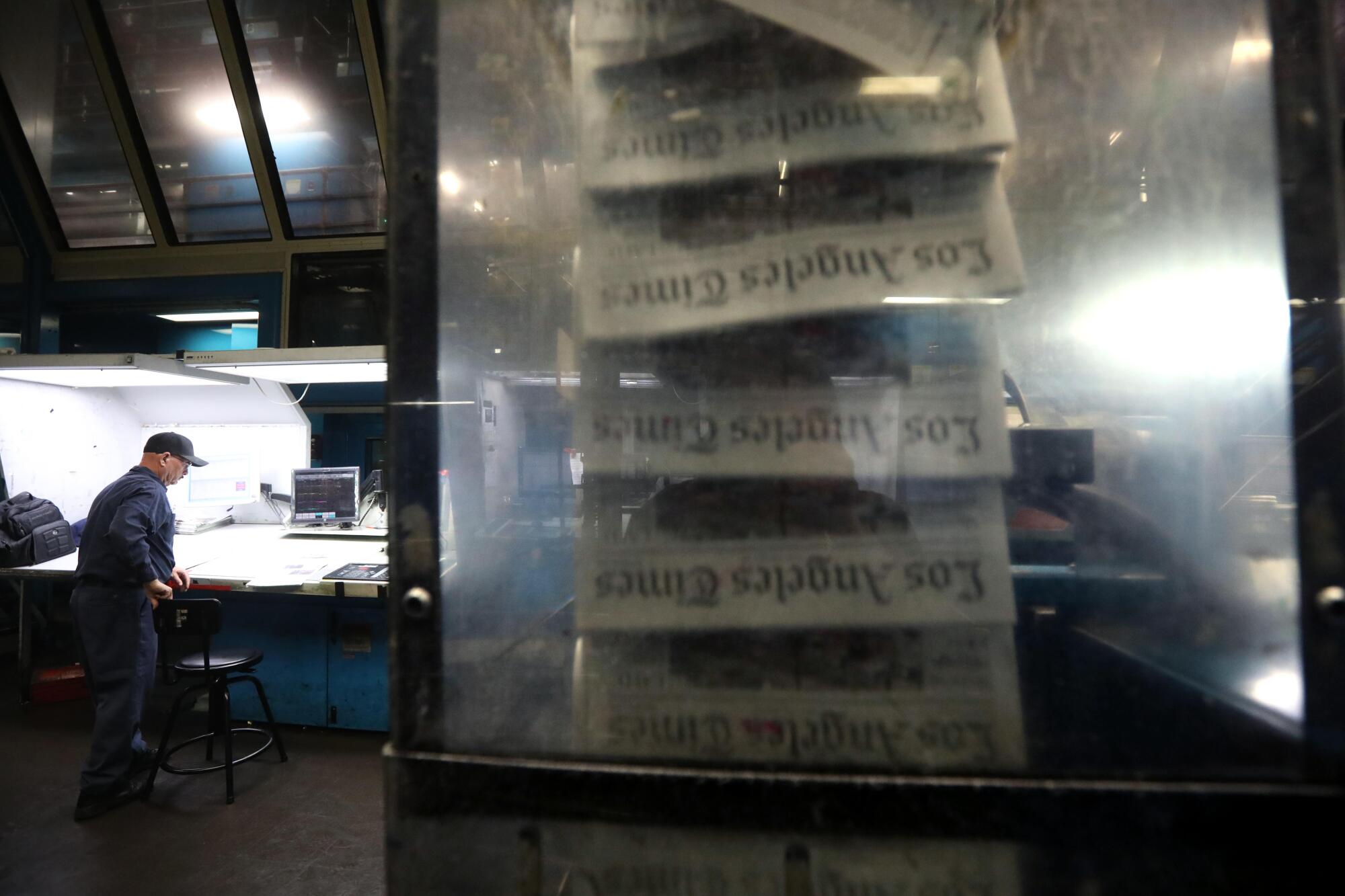

Pressman Mike Carper reviews newspapers at the press console at the Olympic plant.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

The decision was set in motion many years earlier when the Chicago-based Tribune Co., then owner of The Times, sold its historic properties, and The Times became a tenant.

Now, six years after Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong bought The Times in 2018, the lease on the Olympic plant is expiring, and paying rent has become untenable. The paper will be printed in Riverside by the Southern California Newspaper Group, with its circulation numbers remaining the same.

“Technology and economics have changed dramatically, and we’re transitioning to a new era for our business,” Times President and Chief Operating Officer Chris Argentieri said in a statement, citing both the daily newspaper and digital platforms.

March 10 will be the last run of The Times at the Olympic plant.

Dressed in blue pants and blue shirts with a Times eagle patch, the workers find their places throughout the sprawling facility. Each is a crucial link in a chain of production often called the daily miracle: that alchemical transformation of words and pictures into a newspaper to be held, sold, mailed or tossed onto any driveway, any doorstep in the city.

What once was so easy to take for granted has never seemed so remarkable.

They have watched as their crews have been cut, three shifts reduced to one. They once printed other papers besides The Times, and those have gone elsewhere. But it’s hard to be nostalgic over what seems inevitable.

Newspapers have suffered many depredations over the years, from the internet to cost-cutting shareholders to skepticism and disinterest in the written word. With print readership declining in most markets, many media outlets are publishing stories online before printing them. The Times is following this trend, though it consistently ranks among the six largest newspapers in the country for print circulation.

At the Olympic plant, pressman Antonio Garcia, from left, press operator Marc Strong and pressroom supervisor John Wenzel review newspapers to make ongoing adjustments of color and to check whether everything is in register.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

But that’s another story. On this Friday night, Feb. 23, what’s more important is a Ukrainian woman’s search for her husband, a jury’s verdict in a hit-and-run, and in sports, a profile of UCLA’s mercurial basketball coach, as well as the obituaries, comics and horoscopes.

Press operators gather to review the run: Tomorrow’s paper will have color on all but one of the 22 pages. They’ll start at 8:30, print a little more than 100,000 copies and be done in less than two hours.

To step inside the Olympic printing plant is to step inside a time capsule enshrining a 19th century product manufactured with 20th century technology and poised for 21st century obsolescence.

Within these walls was the future of Los Angeles and Southern California, as once imagined by the owners of The Times. Fueled by a diverse economy — a dividend of the postwar boom years — this building, likened by one manager to the Taj Mahal, was dedicated on March 6, 1990. (The paper had been printed on the company’s aged presses in the basement of its headquarters downtown.)

Material handler Gary Cook makes his way past the last few remaining rolls of paper that will be used to print the final editions of the Los Angeles Times at the Olympic plant.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“This was to be a model for the world, not just Southern California,” said Tom Johnson, 82, publisher from 1980 to 1989.

It cost $230 million, the lion’s share of a nearly half-billion-dollar expenditure that saw the construction of a printing plant in Chatsworth and the renovation of an existing production facility in Costa Mesa. Those were halcyon days for The Times, whose revenue in 1991 topped $3.7 billion.

“Come visit the 21st century,” Times readers were encouraged in an advertisement inviting them to tour the new Olympic plant.

Its story was told by numbers: a 26-acre site; a 684,491-square-foot building; six presses capable of printing 70,000 96-page papers per hour; a 400,000-gallon underground water tank for fire suppression; six 6,200-gallon tanks of color ink; a warehouse capable of holding a 65-day supply of paper; and a 148-seat cafeteria for nearly 500 employees.

A view from the catwalk captures newspapers rolling off the presses at the Olympic printing plant.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Beyond the numbers was the Jetsons quality of the place.

Robotic vehicles delivered rolls of paper from the warehouse to machines that fed the presses. Doors opened at the push of a button. Conveyors whisked printed papers to automated bundlers and then to awaiting pallets, hands free.

At the center of it all were the six presses, three on one side and three on the other, running almost two football fields long, connected by a nearly soundproof room with windows angling overhead, providing press operators with easy line of sight and silent escape from the incessant 100-decibel thrum.

The lobby, as elegant as an art museum, was finished in marble and hardwood and featured a glass wall, three stories tall, overlooking the presses that receded far in the distance. In the floor lay a time capsule, a measure of the owner’s faith in the future, to be opened on the paper’s bicentennial: Dec. 4, 2081.

Retired press superintendent Bob Lampher, left, retired pressroom manager Jack Boethling, right, with packaging manager Durga Bhoj, recall the days when they worked in a thriving pressroom while visiting the Olympic plant.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Bob Lampher came to work at the Olympic plant in 1989 as the presses were being installed. He had started at the Times 22 years earlier, “a dream job” after working the presses for the Anaheim Bulletin, the Downey Southeast News and the Costa Mesa Daily Pilot.

“Oly” — as the plant was known — “was the most modern pressroom around,” said Lampher, 82, a retired superintendent. “When I first got here, my jaw dropped. It was simply beautiful, and I thought it would run forever.”

The assumption is forgivable. The Times’ weekday circulation — spread among the Olympic plant, as well as Orange County and the San Fernando Valley printing facilities — was 1.2 million; 1.5 million on Sundays. (Today, success is measured by digital subscriptions, currently close to 550,000.)

To meet that printed volume — for a newspaper so filled with advertising that it ranged from 100 to 200 pages daily (on the Sunday after Thanksgiving 1993, the paper was a whopping 592 pages) — managers choreographed a round-the-clock dance that pushed newsprint through the presses at nearly 30 mph, resulting in close to 60,000 papers printed in an hour.

The sound was like a thundering locomotive. Ink mist and paper dust flew through the air. Margins of error were unforgiving.

Retired pressroom manager Jack Boethling, left, and retired press superintendent Bob Lampher are framed by rollers of a printing press while walking through the Olympic printing plant.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“When you’re doing it, it boggles the mind,” said Lampher, who left The Times in 2002. “I would go back tomorrow just to hear those presses running again.”

His buddy and former press room manager, Jack Boethling, 77, understands. “When you get ink in your veins, there’s nothing like the roar of the presses going at full speed.”

As the swing shift gets underway, Emmett Jaime pries inked plates off cylinders. A Dead Kennedys song plays on a radio boom box, as a bell rings a brief warning each time a cylinder turns.

Jaime, 56, plans to take a little time off before looking for another job. He’d like to work eight more years, but he followed his father to The Times when he was 19 and knows only this world.

John Martin, 60, sits at an operator’s console, studying a copy of a real estate section, whose advertiser is known to be especially picky. He’s making sure the columns of type and photographs sit squarely on the page with equal margins top and bottom.

“It’s been a great, great, great, great run,” he said, describing his 43 years with The Times. When he started, his seniority number was 380. He had hoped one day to make No. 1 but is satisfied to be No. 22.

Pressroom supervisor Kal Hamalainen walks through the paper warehouse that was once a thick forest of rolls stacked five high to the ceiling but is now almost empty.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

In the paper warehouse, Marcus Arnwine, 64, takes a quick inventory of the newsprint. Once a thick forest with rolls stacked five high to the ceiling, it is now a small glade as stock runs low.

“I’m going to miss the wealth of knowledge in this place,” said Arnwine, who started here when he was 20. “There was always someone here who knew something you needed to know.”

Neither Martin nor Arnwine is certain what their next step will be, whether to look for work or retire.

Later that evening, Adam Lee is in the plate room imprinting digital files, produced by editors and page designers, onto aluminum sheets. The air, bathed yellow by safe lights, smells of photographic chemicals and is filled with a rhythmic clicking and a shuttling swoosh.

Lee, 46, is one of the few who has a new job lined up. He started here 18 years ago, joining his stepmother and his uncle, as well his father, who put in 47 years before retiring.

His story is a familiar one: a pressroom of multigenerational employees banking on good benefits, good income and challenging work.

“When we first started,” Hamalainen said, “it was common for an old-timer to take a new hire aside and say, ‘Well, kid, you’ll have a job for life.’ ”

Pressman Sam Pulido ends each night of his shift by depositing the plates stripped from the presses into a bin.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Today in the building’s growing emptiness, they are still a community kept close by their commitment to that work, proud of their craft and eager to dazzle visitors with technical explanations of a job that took years to master: the speed of the paper, the proportions of water and ink, the ability to make a fix on the fly.

They knew there were risks. Some lost fingers in the presses or wrenched knees working on the floor. Some lost marriages to the strain of an unforgiving schedule.

As often as they held history in their hands — the Gulf War, 9/11, the invasion of Iraq, the death of John Wooden, of Kobe and the pandemic — the work never allowed lingering, and they never missed a deadline.

They lived by the clock and by schedules defined by the vastness of Southern California. They had to know when to finish a run to make a 6 a.m. delivery to Santa Barbara, San Diego, Palm Springs.

“Old news doesn’t sell,” Lampher said.

Ink specialist David Oma prepares to pull a newspaper from the conveyor belt to make sure the ink density is proper, the color is in registration, the margins are set, and the date is accurate.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

By 8:44, the presses are rolling at a modest clip. Crews grab from the conveyor early copies being sidelined as waste. They thumb through pages to make sure the ink density is proper, that the color is in registration, the margins are set, pagination perfect, date accurate.

They make refinements and by 9:15 set the throttle to a full gallop, 45,000 papers an hour. Overhead, the newsprint whips by in a blur, running through a succession of cylinders inked cyan, magenta, yellow and black, before converging into a central machine that folds and cuts it into individual papers.

They feel that familiar thrum in their chests. They breathe the moist, almost humid air, and still marvel that such brutish machinery can produce such delicate results.

“It’s like an NFL player who can also be a ballerina,” Hamalainen said. “There is so much strength, power, endurance and finesse in this equipment.”

They find it hard to believe that once they are done, the presses will be dismantled and sold for scrap. The building and the property will be turned into movie and television production studios, said a spokesperson for the owner, Atlas Capital Group.

Pressman Sam Pulido reviews newspapers at the Olympic printing plant, where the L.A. Times will stop being printed as of next week.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Then at 10:31, the pitch of the whirring presses begins to drop as they slow, soon coming to a stop with 107,481 copies printed.

A few minutes later, a voice comes over a loudspeaker: “No finals.”

And they are done. A conveyor clatters as the last papers are carried to the bundlers. The first delivery truck has already left. The last truck will leave at 12:45 a.m.

The swing shift now scatters. Some of the crew strip plates off the presses. Some sit back and read tomorrow’s news, eschewing The Times’ website for the printed paper. A few head to the cafeteria to watch a movie on their phones or to the fitness room for a few reps before heading home.

The witching hour has begun, a disquieting moment for them to have nothing to do. Usually, they’d be cleaning presses and getting ready for another run, but today such diligence doesn’t make much sense.

Hamalainen steps out onto the balcony where some of the crew has gathered.

From this vantage, the Olympic plant has always felt vital to Los Angeles. Two miles away, the skyscrapers of the financial district light up in the night sky, windows glowing against the darkness. City Hall glows blue and yellow in honor of Ukraine on the second anniversary of the war. Distant sirens and horns and the whoosh of the nearby freeway provide the accompanying pulse.

They speak easily among themselves, their emotions masked by familiar banter, old memories and pride.

“It used to be that the quietest time was Sunday morning,” said Hamalainen, once the week’s final run completed at 2:30 a.m.

“Yeah, and in those days, Macy’s was the big advertiser,” said pressman Joaquin Velazquez, 65. He started working at the Olympic plant in 1984. “Remember that? Now, maybe there will be one ad.”

“Used to be a 16-pounder on Black Fridays.”

“Yep, and more than a million papers every day.”

They know they’re running on habit and adrenaline. They know there will be a bit of a freefall once they’re done.

“They’re hiring at the Arizona Republic and the Bay Area News Group and the Las Vegas Review-Journal,” Hamalainen said. “There’s work, but you have to be willing to move away.”

Velazquez draws on his cigarette. Soon, he will no longer be commuting four hours a day from his home in Eastvale.

Retired press superintendent Bob Lampher, left, and retired pressroom manager Jack Boethling walk out of the Olympic printing plant for the last time.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s sad to see it come to an end like this, but we’re blessed to hit the finish line,” Velazquez said.

“You know, I think I’m going to sneak back in, just to see it all cleared out,” Hamalainen said. “This is going to be one big empty building.”

This story originally appeared on LA Times