Alan Arkin’s Little Murders, Arkin’s stunning 1971 feature directorial debut, based on the stage play of the same name by Jules Feiffer, is a dark and merciless examination of paranoia and urban horror that inspires stunned, uncomfortable laughter from viewers. Indeed, how can someone laugh after watching someone indiscriminately shoot people to death with a rifle from an apartment window, and what does it say about a person who would laugh at such a scene?

A forerunner of such New York-based urban terror films as After Hours, Cruising, Death Wish, and Taxi Driver, Little Murders stands apart from these later films by presenting a portrait of a New York that is as much gripped by a reign of apathy as terror.

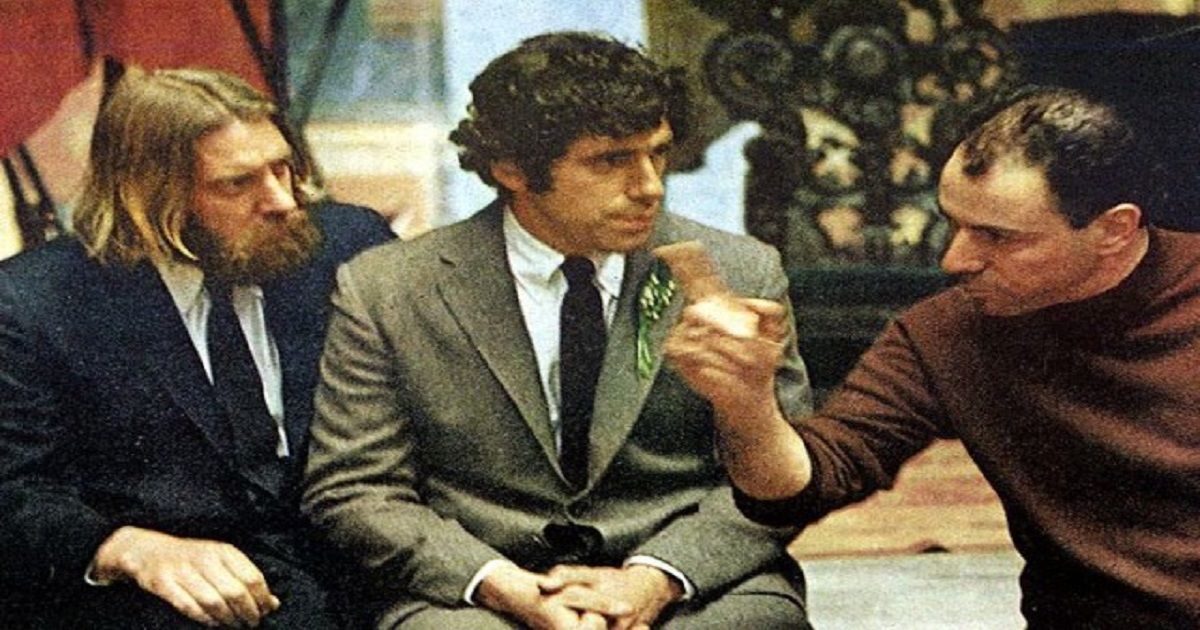

As the director, Arkin, who also appears in the film as an emotionally-damaged police lieutenant, portrays New York as a hopeless and masochistic state of badly-timed power outages, garbage strikes, obscene phone calls, random shootings, and an abundance of unsolved murders—345 unsolved murders to be exact.

However, Arkin burrows much deeper in the film to expose an urban wasteland that functions to batter and defeat its citizens, who are reduced to retreating inside themselves instead of communicating with one another. In this regard and others, Little Murders might be more relevant to today’s human condition than it was in the early 1970s.

Laughing to Keep From Crying (And Dying)

In Little Murders, Alan Arkin, who directed a 1969 off-Broadway production of Little Murders, establishes a tone of defeatism and resignation in the film’s opening scene, in which a woman named Patsy, an interior decorator, played by Marcia Rodd, is asleep in bed, only to be awakened by an obscene phone call, a seemingly daily occurrence for her. Indeed, she seems to be as unaffected by the existence of an obscene caller as she is by the steel window shutters that “decorate” her apartment.

While Patsy seems absolutely unfazed by the heavy-breathing caller, she is jolted by the sounds of a man being attacked by thugs outside her apartment window. Running outside, she finds the victim, Alfred Chamberlain, an emotionally-deadened photographer who, as played by Elliott Gould, has arrived at the sad realization that the only way to avoid feeling pain is to not feel anything.

Patsy, who has adopted a note of eternal optimism to allow her to navigate the stream of muggings, obscene calls, and shootings that represents her everyday existence, becomes a catalyst figure for Alfred, who is subsequently introduced to Patsy’s dysfunctional family and falls in love with Patsy, who desperately wants Alfred to be happy with her, of course, but also to fight back against the isolating effect of the city by allowing himself to become reattached to basic human feelings if not outright happiness and joy.

Needless to say, Patsy, much like a first-time viewer of Little Murders, is completely unaware, and would be shocked to discover, that Alfred’s ultimate transformation will extend from detached victim to detached apartment shooter.

This Damn City

With the scenes that involve Alfred and Patsy’s relationship, from courtship to marriage to married life, Alan Arkin demonstrates with Little Murders how city life functions, either directly or indirectly, to cause its citizens to become detached from basic human emotions and each other.

In Little Murders, this is crystallized when Patsy is eventually “defeated” by the city of New York, as Patsy, in a scene that is more shocking in terms of its arbitrariness and directness than its implications, is killed by a faceless sniper. Following Patsy’s murder, a blood-spattered Alfred heads for Patsy’s parents’ apartment by way of a New York subway train, in which Alfred’s bloody and shell-shocked appearance barely registers with the seemingly oblivious passengers.

At this point, Little Murders comes closest to becoming the same sort of communal viewing experience that is represented by Death Wish and Taxi Driver, as the viewer is inclined to seek vengeance alongside Alfred, just like with Death Wish vigilante Paul Kersey and Taxi Driver anti-hero Travis Bickle, until Alfred buys a rifle during a walk in Central Park and then subsequently commences the aforementioned shooting of random citizens in Patsy’s parents’ apartment.

Indeed, by the end of Little Murders, the numbing effect of the rampant desensitization that has broken down the film’s characters has also, quite possibly, altered the viewer to the point where one simply doesn’t know whether to cry or laugh.

Little Murders Is a Great Film

The film version of Little Murders was a great triumph for Alan Arkin, who, besides having directed the 1969 stage production of Little Murders, also directed two short films before the filming of Little Murders began in April 1970.

Although Little Murders, which had a budget of approximately $1.3 million, was a modest box office success, the film received generally excellent reviews. However, despite the widespread acclaim that Little Murders received, Arkin’s directorial career essentially languished throughout the rest of the 1970s.

After Little Murders, Arkin, who received a Tony Award nomination in 1975 for his direction of the Neil Simon comedy play The Sunshine Boys, only directed one more feature film, the 1977 comedy film Fire Sale, which was a commercial and critical failure.

After the disappointment of Fire Sale, Arkin essentially abandoned directing in favor of his acting career, which, of course, eventually resulted in a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Arkin’s memorable performance in the 2006 film Little Miss Sunshine.

This story originally appeared on Movieweb